There is terror in the empty places.

You might find this out if you ever decide to drive through some of the more featureless parts of this country, like, say, the Texas Panhandle or Trans-Pecos region of Texas. It can get eerie fast in the Chihuahuan Desert, you can feel like a bullet singing toward some inevitable full-stop end. Makes for a kind of fatalistic freedom.

Troy Falconer -- the surname evokes the 1977 John Cheever prison novel about an academic imprisoned for fratricide who later escapes, but I'd need to reread the old novel before making any further claims -- knows this kind of terrible freedom, this kind of fatalism. As a kid scared of heights, his father, Bill Ray, carried him onto the roof of their house where he experienced "the sweep of the sky ... so big that, lying on your back and looking up into it, you sometimes experience the sensation that you will come loose from the earth, and fly up with nothing to catch on to."

Now Troy is a refusenik of late capitalism, living from stolen car to car and off things he burgles from cheap motel rooms in the Panhandle. A century before he might have been a horse thief, his crimes taken a bit more seriously. Had he more courage he might have become a monk.

Something snapped in his head one night, and he took the only kind of vow that made sense given the limits of his imagination. He dedicated himself to "the careful and highly precarious maintenance of a life almost completely purified of personal property." He owns nothing, he makes use of what stealth and habit provide. He wears the clothes of salesmen and livestock judges. He drives their dull sedans and pickups for a day or two. It's 1972. He's flying. He loses momentum, he crashes. He knows the road is running out.

Troy has no home, but he returns to what used to be his father's place after being away six years. He's looking for his younger, bigger brother Harlan, their father having passed on. Breaking and entering confirms the house is now occupied by an earnest family, headed by a lawman. He recognizes some of the furniture, but Harlan has moved on.

He finds his brother in much reduced circumstances thanks to a woman who loved him in bad faith. Troy rightfully feels a little guilty about that, but maybe he feels worse that she conned him too. So the brothers set out to find her, setting up what you suspect might be an odd couple road trip comedy, but things start to slip sideways when Harlan's antique truck gives out and Troy does what he does and steals a station wagon from a grocery to keep them in motion.

What they don't notice is Martha, the 11-year-old Mennonite girl hiding in the floorboards of the back seat.

How Martha came to be in the backseat of that station wagon in a parking lot in Tahoka, Texas, is itself a yarn, one that's braided through Troy's first-person confessions and a third-person narrative of the road trip. She has some of the grit of Charles Portis' Mattie Ross; she is precocious, brave, a little too well-spoken and credibly strange.

All the characters and specific details feel like they've been sketched from life, and I imagine that first-time novelist Randy Kennedy spent a lot of time researching the sparse flora of the region and the Mennonite population in northern Mexico.

Or maybe he knew it already, because I see by the promotional material that he was born and reared in west Texas, in a town called Plains that I've been through and thought nothing at all about. I imagine he was eager to get out of there, and by 1992 he was a cityside reporter with The New York Times. He later started writing about the city's art scene. Recently he took a job as the director of special projects at Hauser and Wirth, an art gallery with locations in Zurich, London, New York, Somerset, Los Angeles, Hong Kong and Gstaad.

I don't know what kind of work that sort of job entails, but it sounds cool.

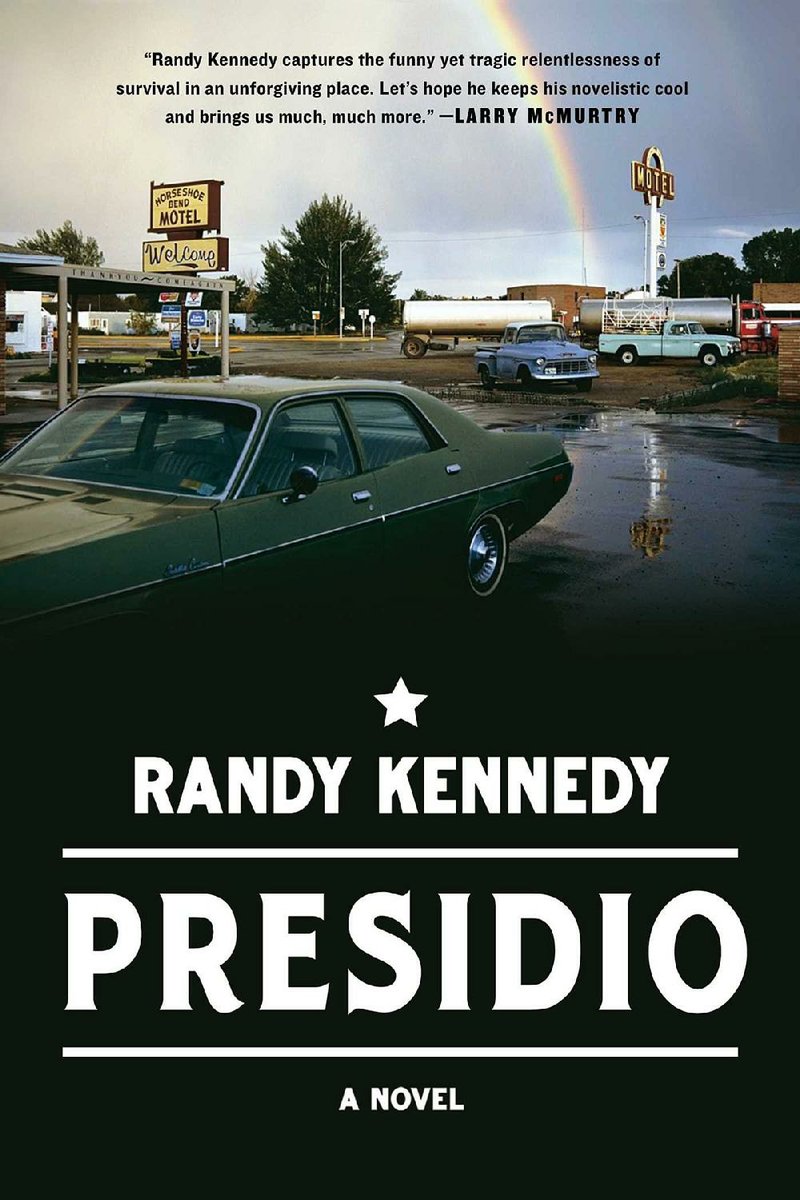

Presidio's cover sports a blurb from Larry McMurtry, who has been notably tough on home state regionialists before, while the back is graced by an Annie Proulx quote. So one can assume there is a big marketing push, and for once the book deserves it.

After I finished reading it, I loaned it to my colleague Sean Clancy, who also liked it and compared it to Jim Thompson. I'd like to think I would have come up with that point of reference on my own because it's so apt, but I'm not sure I would have. Only Troy, for all his weakness, is more seeker than cynic; he doesn't really have the heart to be a grifter. He's scared all the time, he's just developed a talent for looking cool.

Which makes him one of the classically American protagonists, a gone-crazy who under other circumstances might have turned out to be a sweet kid. Troy got put on a trajectory early, a missile that could not be recalled.

Email:

blooddirtangels.com

Style on 08/26/2018