Walmart has a vast arsenal at its disposal in its battle with Amazon.com: stores, trucks, warehouses, even a blockchain-enabled supply chain of fruits and vegetables.

But there's one weapon it's barely deployed: Vudu, the video-on-demand service it bought eight years ago.

Back then, Netflix was available only in the U.S. and Canada, Amazon was still a year away from offering free videos for its Prime members, and Apple had just released its first iPad. With a library of 5,000 films from all the big studios available at the press of a button, Vudu promised to "revolutionize" the home-movie experience when it debuted in 2007.

It hasn't worked out that way. As its competitors flourished, Vudu languished. Even though it's pre-loaded in or can be downloaded to hundreds of millions of smart TVs, Blu-ray devices and video-game consoles -- thanks to Walmart's enormous clout with electronics makers such as Sony and Samsung -- users spend just 1.9 hours a month on the platform, according to data tracker comScore. This compares with the 25 hours a month subscribers spend on Netflix.

"People are renting and buying less because they are binge-watching more," said Colin Dixon, founder of industry analyst firm nScreenMedia. "That's not good for Vudu, which is far, far behind the leaders."

Vudu gave Walmart digital cred, but the primary rationale for the 2010 deal was to provide insurance against declining in-store sales of DVDs. Walmart bet that video buffs would continue to buy and rent loads of movies -- they'd just move their titles to a digital shelf, or library, that Vudu would create and maintain for them.

While Walmart sits on the streaming sidelines, the competition is moving on. Netflix's subscription-based approach -- featuring cutting-edge, exclusive content such as House of Cards and Stranger Things -- has been on a global-growth tear. Amazon's spending billions on its own programming to catch up while offering hit shows from HBO and Showtime. And Disney is planning its own streaming service, which will debut in 2019.

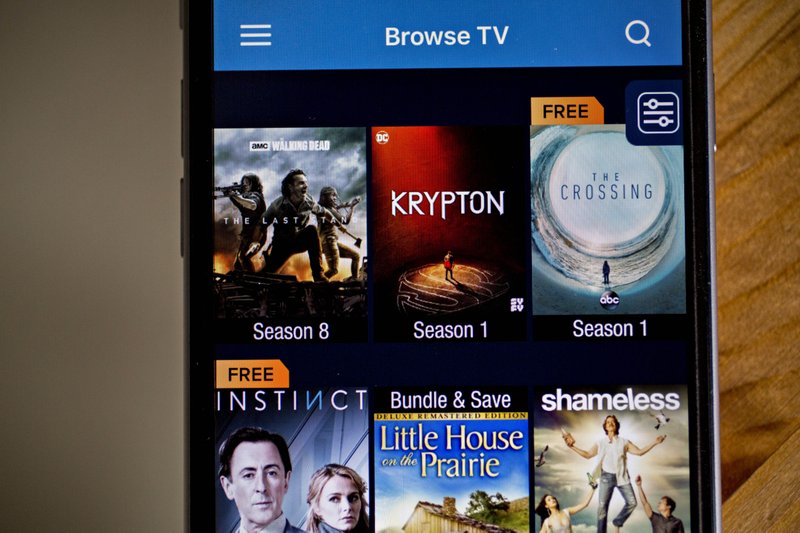

All told, there are more than 200 over-the-top video services, so called because they bypass cable providers and stream content directly to a TV, laptop, phone or game console. That's up from 68 five years ago, according to market researcher Parks Associates.

Vudu hasn't been completely idle. It holds Twitter-based "viewing parties" where users can interact with other fans online and win prizes, like the one it held for Jumanji: Welcome to the Jungle in March. And Walmart will convert old discs into digital copies, for a fee, and house them in a user's Vudu library. The retailer also offers in-store promotions, such as a $15 Vudu credit with the purchase of a Roku streaming stick.

In late 2016, the unit began offering some movies for free if viewers didn't mind watching ads. That's helped boost viewership by 56 percent in the past year, according to comScore.

"It's been really good for us," said Jeremy Verba, Vudu's general manager. "It's brought in new customers, and our existing customers spend more time and money with us."

One of those customers is Brandon Powers, a 36-year-old in Brockton, Mass., who buys from Vudu once a week and enjoys being able to convert the discs he already owns.

"They have an advantage that Amazon does not have: physical contact with millions of shoppers every week," said Tony Miranz, who co-founded Vudu in 2004 and now runs an artificial-intelligence startup.

But the big prize is subscription streaming. With almost 1 million new U.S. households streaming video every month, the market is expected to grow to $84 billion by 2022 from $35 billion last year, according to Jim O'Neill, editor of video-industry publication Videomind. The average family uses between three and four different services, mainly Netflix, Amazon Video, YouTube and Hulu.

"It's like keeping a star quarterback on the sidelines," Miranz said. "With the flip of a switch, they could compete with Netflix."

That's easier said than done. For Walmart to seriously compete, it would have to devote resources -- both creative and financial -- toward providing original Walmart-branded content as Netflix, Amazon and Hulu have all done.

Walmart would do best by becoming an exclusive destination for light, family-friendly fare alongside a partner like the Hallmark Channel or Discovery Co.'s Scripps Network, according to Forrester Research analyst James McQuivey. That's because, he said, most original content is of the R-rated variety for adult viewers.

"There is a gap in the original content-market, and Walmart is most definitely the company that could fill it," McQuivey said.

If it doesn't, others certainly will. Last year viewers enjoyed a record 487 original scripted shows, up 70 percent from 2012. Nearly one-quarter of those were from streaming services. None were from Vudu.

"They need to give people a real reason to come," Dixon said.

SundayMonday Business on 04/01/2018