When Robert Weil, the editor-in-chief and publishing director of Liveright, approached Henry Louis Gates Jr. and Maria Tatar with the idea of putting together The Annotated African American Folktales the two Harvard professors responded with a mix of excitement and trepidation. The world of black lore is geographically expansive and substantively diverse. But Weil was convinced that the two scholars were up to the task.

"I just felt in my bones that if they could combine their backgrounds, they could create an extraordinary, but also historically important, work," he said.

So Weil connected the two over email and took a step back, giving them the space to research and think through the details.

"The question we both asked ourselves was why African-American folklore vanished," said Tatar, a professor of folklore and mythology who has edited annotated volumes of the Brothers Grimm and Hans Christian Andersen stories. For decades, black folklore failed to capture mainstream attention and remained in a perpetually precarious position, always on the verge of being lost. Gates and Tatar wanted to change that.

"Maria brought an impressive, unique knowledge of the history of folk tales," Gates said. And "I brought my knowledge of African-American vernacular tradition."

As the two academics pored through materials, their goal remained the same: to introduce young readers to stories that have been passed down from generations and across continents.

"I am very much concerned that black kids see themselves as part of a global black experience," said Gates, who is the director of the Hutchins Center for African and African-American Research at Harvard.

This is, of course, in line with Gates' mission -- as seen in his PBS series Finding Your Roots and his recently published 100 Amazing Facts About the Negro (Pantheon) -- to expand the understanding and appreciation of the contributions of black people across the diaspora.

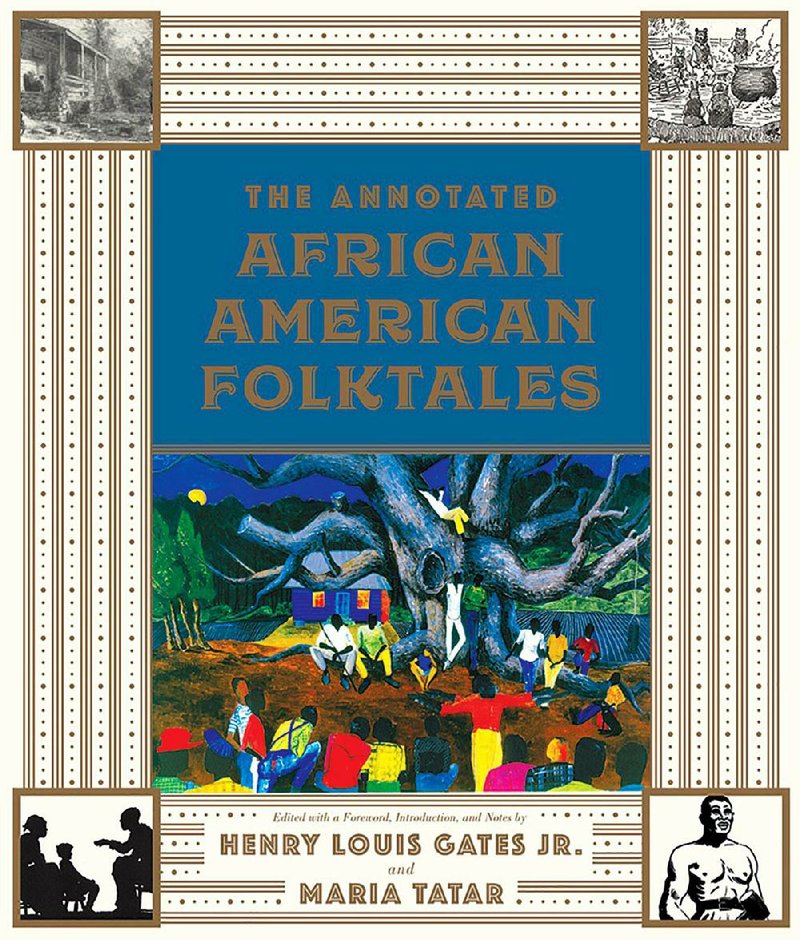

The Annotated African American Folktales (Liveright/W.W. Norton) contains more than 100 black folk tales as well as introductory essays and commentary to provide historical context. It draws from the rich, undersung work of folklorists from West Africa to the Deep South.

Garbo Hearne, owner of Pyramid Books in Little Rock, says the book "is a great tool for a parent to use to teach morals, character ... it can help parents and children have critical conversations."

The Annotated African American Folktales begins with the Anansi tales of West Africa, stories featuring a trickster character who is a human and a spider, a decision that Tatar describes as "pragmatic" because so many of the later tales borrow from these foundational myths.

From there, they follow the tradition to the United States, where tales about magical instruments and flying Africans played a significant role in the lives of slaves, inspiring resistance and enabling a sense of community. The last half of the book takes a more scholarly turn, considering the work of folklorists such as Zora Neale Hurston and Jessie Redmon Fauset, the editor of the first magazine for black children. There is also a chapter dedicated to The Southern Workman, a monthly journal of the Hampton Institute founded in 1872 to explore the achievements of black Americans.

Gates and Tatar also tackle controversial parts of folklore history, dedicating a chapter to the work of Joel Chandler Harris. Born in Eatonton, Ga., in 1848, Harris, who was white, established his reputation in American literature with his Uncle Remus series, stories about an old black slave who told his young white master tales about wily animals such as Brer Rabbit and Brer Fox. The stories were written in dialect and tried to evoke images of a nonexistent idyllic life on Southern plantations. They inspired Walt Disney's 1946 film Song of the South, which has fallen out of favor because of its racist overtones, but they were also "the first large-scale effort to collect African-American lore" and emboldened black Americans such as Charles Chesnutt, the author of The Conjure Woman, to reclaim the stories, Gates said.

The decision to include Harris' work in this collection produced lively discussions between Gates and Tatar. "I felt uncomfortable with it," Tatar said. But Gates disagreed. The exchange proved to be a key moment of collaboration.

"In my house, growing up in Piedmont, W.Va., we collected Mother Goose and Joel Chandler Harris," he said. "My father used to tell Brer Rabbit stories to my brother and me all the time."

These conversations led to "a much deeper understanding of the larger stakes in the project," Tatar said. Like the history of America, the history of folklore is messy and complicated. In the late 19th century and early 20th century, black people debated whether these folk tales were worth preserving. Some people considered the stories remnants of slavery rather than evidence of ingenuity.

The novelist Toni Morrison, however, has played an important role in validating these stories by integrating them into her writing, Tatar said.

While Morrison's novels contain traces of innovative uses of folklore, Tar Baby is the most obvious and the one Gates was particularly eager to include in this collection. Not only is it one of his favorite stories, he also finds the appearance of the tar baby in many cultures "haunting." The original folk tale is the story of Brer Fox and Brer Rabbit. Angry that Brer Rabbit is always stealing from his garden, Brer Fox makes a tar baby. Brer Rabbit comes across the figure and tries to start a conversation. He grows frustrated by the lack of response and hits the tar baby, only to find his paw stuck in what is a doll made of tar and turpentine.

In her 1981 novel, Morrison mines this folk tale to create a love story between two black Americans from very different socio-economic backgrounds. According to a Times review, the novel spoke to the black person's "desire to create a mythology of his own to replace the stereotypes and myths the white man has constructed for him."

It isn't just Morrison who has used black folklore for inspiration; Nnedi Okorafor and Marlon James have also turned to it in their prose. Okorafor recently published the second novel in her Akata series, and James is working on an epic fantasy trilogy that draws from African mythology and folklore.

"Whoever created the Anansi stories was a genius," Gates said. Indeed, he and Tatar are grateful to those such as Hurston who collected these stories before them.

Folk tales give us "ancestral wisdom," they teach children lessons about compassion, forgiveness and respect, Tatar said. They take us "back to the people who lived before us." They help us "navigate the future."

Gates couldn't agree more. He has dedicated this labor of love to his 3-year-old granddaughter. He wants the book to be not just for her and black children of her generation, but for all American children.

Ellis Widner contributed to this report.

Style on 04/01/2018