FAYETTEVILLE — The city will set a course to run entirely on renewable energy by 2050 if it adopts a proposed plan.

Keeping track

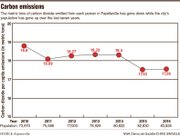

Fayetteville has tracked its greenhouse gas emissions since 2010. To counteract the carbon output of one resident, it would take 456 trees, each at least 10 years old, on about 17 acres, according to the city’s sustainability department. Bentonville tracks its energy usage because it provides electrical service to residents. Springdale and Rogers generally don’t keep that sort of data, officials said, but have tried to cut down on energy usage when feasible.

Source: Staff report

The Energy Action Plan would tackle greenhouse gas emissions through four measures: increasing energy efficiency in new and existing buildings, expanding the city’s clean energy supply, cutting vehicle emissions and keeping more trash out of the landfill.

What do you think?

Let the city know your thoughts about the Energy Action Plan:

In person

9 a.m. to 1 p.m. Saturday, Farmers Market on the square 10 a.m. to 2 p.m. Wednesday, library

Online

surveymonkey.com/r/… ActionPlan

Read the plan:

fayetteville-ar.gov… ActionPlan

Source: Staff report

City officials said they want to lead by example. By 2030, all city-owned buildings and vehicles would be powered by renewable energy such as wind, solar, hydroelectric and organic power, according to the plan. The rest of the city would follow 20 years later.

The public comment period has begun for the plan, the first draft of which came out Sept. 29. City officials partnered with utility companies, energy industry specialists, construction contractors and other relevant groups to come up with the plan.

The City Council will take a close look at it after its agenda session Tuesday. A final version should be ready for the council to vote on by late fall.

Proponents say the city must take action in light of the federal government’s resistance to sustainability and the long-term benefits and savings will offset the upfront costs.

Rick Perry, U.S. energy secretary, told congressional leaders during his confirmation hearing in January he would advocate for American energy in all forms. He has frequently boasted Texas, the state where he was governor from 2000-2015, as the top producer of wind energy in the United States.

However, Perry has said anti-carbon programs could cost billions or trillions of dollars, and the country shouldn’t spend so much money to counter the unproven scientific theory that carbon emissions contribute to global warming. In a June interview with CNBC, Perry described oceans as the primary control knob impacting the planet, not carbon or other greenhouse gases.

President Donald Trump has proposed several cuts to the U.S. Department of Energy, including a 70 percent reduction to the Office of Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy, from $2.1 billion to $636 million. Trump also announced in June the United States would withdraw from the Paris Agreement, a United Nations accord signed in 2016 to curb gas emissions.

Critics say the Fayetteville codes and regulations are already costly and burden developers and business owners.

SEEING BENEFITS

The city tracks its greenhouse gas emissions by getting raw data on usage from electric and gas companies, information from the Arkansas Department of Transportation on the number of drivers on the road, inventory at the Tontitown landfill and the city’s own solid waste department, said Rachael Schaffner, project coordinator with the city’s sustainability department.

Power used in buildings in Fayetteville, both commercial and residential, account for 66 percent of greenhouse gas emissions coming from the city, according to the plan’s estimates.

Under the plan, city officials would periodically analyze and possibly revise the building code to maintain energy efficiency. The goal is to get a 3 percent annual reduction in overall energy usage.

The city wants to take a two-pronged approached with buildings. The first is how much energy a building uses, which relates to efficiency, said Peter Nierengarten, the city’s sustainability director.

The city wants new buildings to be built with efficiency in mind and for additional existing buildings to become more efficient. Incentive programs, such as the national Property Assessed Clean Energy program, gives homeowners a loan to retrofit their houses. The amount paid back on the loan ends up being less than the combined savings in utility bills over 20 years, he said.

Andrew Garner, city planning director, said the city has adopted a number of energy efficiency measures into its code, such as the Home Energy Rating System index, which is the industry standard in making homes energy efficient.

New commercial structures have to comply with the 2011 Arkansas Energy Code. The city requires new residential structures to adhere to the standards set by the 2009 International Energy Conservation Code. The plan includes adopting additional efficiency measures outlined in the 2012 revision of the international code.

“Politically, that might be difficult to have any further upgrades to take us even further ahead of other cities,” Garner said. “We are, in my opinion, way ahead of some of the other cities in terms of energy code for our single-family homes.”

TALLYING COSTS

Adding regulations means higher costs for builders, which ultimately hurts the city, said Tracy Hoskins, a developer and business owner who formerly served on the Planning Commission.

Builders pass higher construction costs to homeowners, and at a certain point, people will stop buying homes in the city, he said. Homes stop getting built or get built elsewhere when that happens, Hoskins said. The city’s code book is already overbearing for developers, he added.

There’s nothing wrong with requiring good construction, Hoskins said. But builders have been doing good work for a long time without academics coming up with standards city officials turn into requirements, he said.

“Their definition of properly constructed and the real-world definition of properly constructed are two different things,” Hoskins said.

Solar panels have gotten less expensive, but the practicality of the technology has a way to go, said Flint Richter, owner of Richter Solar Energy in Fayetteville.

Richter mostly served residences literally off the grid who needed a power source when he got in the business 18 years ago. Business has increased since then, he said, and panels that cost $10,000 a decade ago now can go for a few hundred dollars.

However, Richter doesn’t expect to see subdivisions lined with solar arrays anytime soon. A commercial system can pay for itself in 10 years, and a residential one can have a full return on the investment in 15 years, Richter said. It’s getting over the upfront cost that’s the challenge.

For example, the average home solar system costs in Arkansas about $22,000. A federal tax credit could reduce the cost by about $6,600, which would leave the final investment at $15,400. The system would produce $1,200 of electricity yearly at current rates, he said.

“We’re still in the infancy of this industry,” he said. “It’s still expensive.”

A CLEAN CITY

Buildings contribute so greatly to the total of greenhouse gas output because of where their electricity generation, natural gas and water treatment comes from, Schaffner said. Electricity for most buildings in the city comes from a coal-fueled power plant. Natural gas production has a certain amount of greenhouse gas emission associated with it.

The city’s two wastewater treatment plants, in particular, make up more than half of the greenhouse gas emissions from city-owned facilities, Schaffner said. The treatment and pumping of the water contributes significantly, she said.

Alternative energy sources have become more prominent, Nierengarten said. He pointed to Ozarks Electric Cooperative’s 4,080-panel, one-megawatt solar facility in Springdale. Southwestern Electric Power also has announced a $4.5 billion project to build a 2,000-megawatt wind farm in Oklahoma’s panhandle.

The fact utility companies are increasingly investing in forms of energy other than coal serves as the writing on the wall, Nierengarten said. The planet is not getting any cooler, and it’s become more apparent that change will have to happen at the local level, he said.

“This is our next step beyond just committing to doing it. Like, this is how we’re going to do it,” Nierengarten said of the proposed plan.

Other recommendations in the plan include at least one electric car charging station for every 10,000 residents. The city would start a bike-share program. Eighty-five percent of residents would live within one-third of a mile of a heat island mitigation feature, which is vegetation specifically grown to cut the sultry effects of the sun reflecting off pavement, buildings and cars. The city’s tree canopy would reach 40 percent, up from 34 percent now.

Trees serve as an easy way to accomplish several of the plan’s goals, said Lee Porter, one of the city’s urban foresters. They help cities cool, especially at night after the sun’s rays have left a lingering effect.

“The leaves on trees are lungs of trees,” she said. “They’re breathing, and they’re releasing fresh air, capturing poor quality air and processing that. It goes the same with heat.”

The city’s new recycling plan and an update to its transportation plan largely will cover the other half of the Energy Action Plan’s objectives.

The City Council unanimously adopted a recycling master plan in February that calls for diverting 40 percent of waste from the landfill in 10 years. An upcoming transportation and mobility plan would make traveling by means other than a car easier. Much of that plan focuses on connecting gaps in the trails and sidewalks systems.

TRENDING TOGETHER

A few cities have made the move to 100 percent renewable electricity.

Aspen, Colo., became one of the first cities in the nation to run entirely on renewable energy in 2015, according to a July National Public Radio report. The city signed contracts to bring in hydro-power, wind and biogas from outside states.

A handful of other cities join Aspen, according to NPR’s report: Georgetown, Texas; Burlington, Vt.; Greensburg, Kan.; Rockport, Mo.; and Kodiak Island, Alaska. All use 99 percent renewable energy and a small amount of diesel as a backup fuel source.

Fayetteville based its clean energy goals on a national initiative from the Sierra Club to get more cities on the 100 percent renewables train. Mayor Lioneld Jordan joined 149 other mayors in the Sierra Club’s Ready for 100 campaign. The 150 cities account for 5 percent of the nation’s electricity usage, according to the club’s website.

“I see that the market is making renewables much more widespread and cost effective,” Jordan said. “In the near future, renewables will save citizens money, which will drive this transition while improving quality of life, promoting energy independence and reducing our greenhouse gas emissions.”

Stacy Ryburn can be reached by email at [email protected] or on Twitter @stacyryburn.