WASHINGTON -- The Supreme Court on Wednesday heard arguments in a case in which the government obtained 127 days of cellphone tower information, without a search warrant, that allowed it to place a criminal suspect in the vicinity of robberies.

Underlying the 80-minute argument was unease about how technological advancements have facilitated the tracking of so many aspects of American lives. Some of the justices voiced concerns about the government's ability to track Americans' movements through the collection of their cellphone information.

"Most Americans, I think, still want to avoid Big Brother," Justice Sonia Sotomayor said, adding that Americans take their phones with them to dressing rooms, bathrooms and bed.

Chief Justice John Roberts, reprising a line from an earlier opinion, noted that having a cellphone these days is a matter of necessity, not choice.

[U.S. SUPREME COURT: More on current justices, voting relationships]

With those devices, Justice Elena Kagan said, authorities have the ability to do "24/7 tracking." And the accuracy of cell tower location information also has improved from a vicinity of 10 football fields to half the size of the courtroom in which the argument was occurring, she said.

In question is whether the Constitution's Fourth Amendment protection against unreasonable searches should apply to police collection of cellphone tower information that has become an important tool in criminal investigations.

Sotomayor, Roberts and Kagan appeared to be leaning toward that outcome.

The cell tower records that investigators got without a warrant bolstered their case against Timothy Carpenter in a string of robberies of Radio Shack and T-Mobile stores in Michigan and Ohio.

Investigators obtained the cell tower records with a court order that requires a lower standard than the "probable cause" needed to obtain a warrant. "Probable cause" requires strong evidence that a person has committed a crime.

The judge at Carpenter's trial refused to suppress the records, finding no warrant was needed, and a federal appeals court agreed. President Donald Trump's administration said the lower court decisions should be upheld.

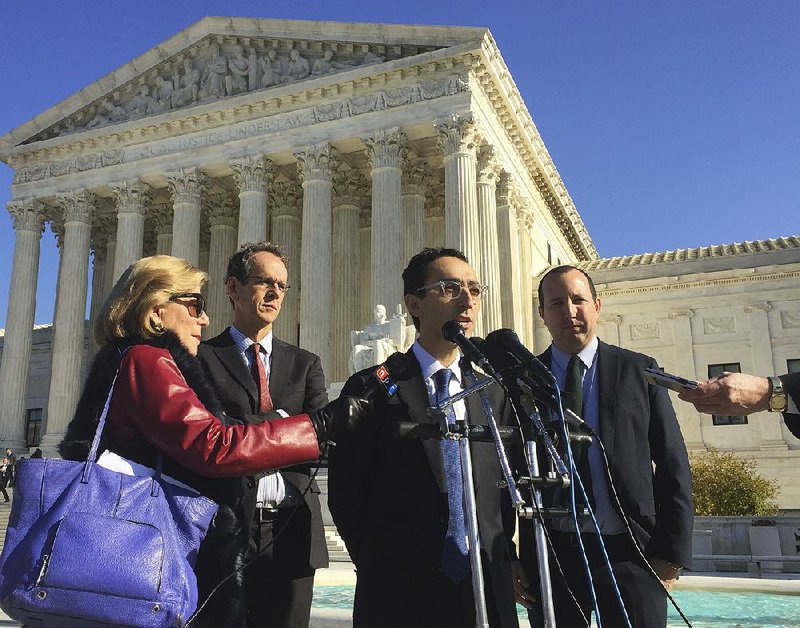

Arguing before the Supreme Court, American Civil Liberties Union lawyer Nathan Freed Wessler said a warrant would provide protection against unjustified government snooping.

On the other side, Justices Samuel Alito and Anthony Kennedy seemed most receptive to the administration's argument that privacy rights do not come into play when the government gets records from telecommunications providers and other companies that keep records of their transactions with customers.

Alito said most people would not be shocked to learn that cellphone towers can help locate them.

"I mean, people know. There were all these commercials, 'Can you hear me now? Our company has lots of towers everywhere.' What do they think that's about?" Alito asked, referring to a onetime Verizon Wireless ad campaign.

Justice Department lawyer Michael Dreeben said, "The technology here is new, but the legal principles the court has articulated under the Fourth Amendment are not."

The administration relied in part on a 1979 Supreme Court decision that treated phone records differently than the conversation in a phone call, for which a warrant generally is required.

The court said then that people had no expectation of privacy in the records of calls made and kept by the phone company. That case involved a single home telephone.

The Supreme Court in recent years has acknowledged technology's effects on privacy. In 2014, the court held unanimously that police must generally get a warrant to search the cellphones of people they arrest. Other items people carry with them may be looked at without a warrant, after an arrest.

Courts around the country have wrestled with the issue. The most relevant Supreme Court case is nearly 40 years old, before the digital age, and the law on which prosecutors relied to obtain an order for the records dates from 1986, when few people had cellphones.

Dreeben said federal agents obtained the order before examining cellphone location records after "a bullet was fired through the window of a federal judge in Florida."

The court has several options if it sides with Carpenter. It could declare the need for a warrant any time police want cell tower records. Or it could say a warrant is needed only when seeking records over a period of time. The ACLU suggested a warrant for anything more than a day's worth of records.

The justices also could say that obtaining the records is a search under the Fourth Amendment, but a reasonable one because a judge signed off on it.

Even if Carpenter wins at the Supreme Court, it may not matter to his conviction or 116-year sentence.

"Is any of this going to do any good for Mr. Carpenter?" Alito asked.

A Section on 11/30/2017