"Everybody loves Tom Petty and burritos."

-- Marc Maron

An ancient emperor with an odd sense of humor gathered his wisest sages and asked them to come up with the saddest sentence ever written. The sages conferred and went off to think upon the subject. Weeks later they approached the emperor and humbly handed him a slip of paper on which were written the words:

"Someday Bill Murray is going to die."

OK, I made that up. The part about the ancient emperor at least; I don't remember where I got the "Bill Murray" part from, but I saw that somewhere, probably on social media. I stole it because it felt true to me.

If you're of my generation, or a little bit younger, maybe it feels true to you too. Because most of us like Murray, probably more for the light way he lives on the earth than for any of the movies he has made or his time on Saturday Night Live, although Murray's performances certainly inform the warm feelings you (probably) hold about him.

And the joke -- if you can call it a joke -- doesn't have to invoke Murray. It might have worked just as well if I'd used the name "Tom Hanks." (I'm sorry but I can't think of a current female performer so universally loved and admired that her name would work in the joke, which might say something about how our society regards women who court public attention, though "Carol Burnett" or "Mary Tyler Moore" would have worked in the past.)

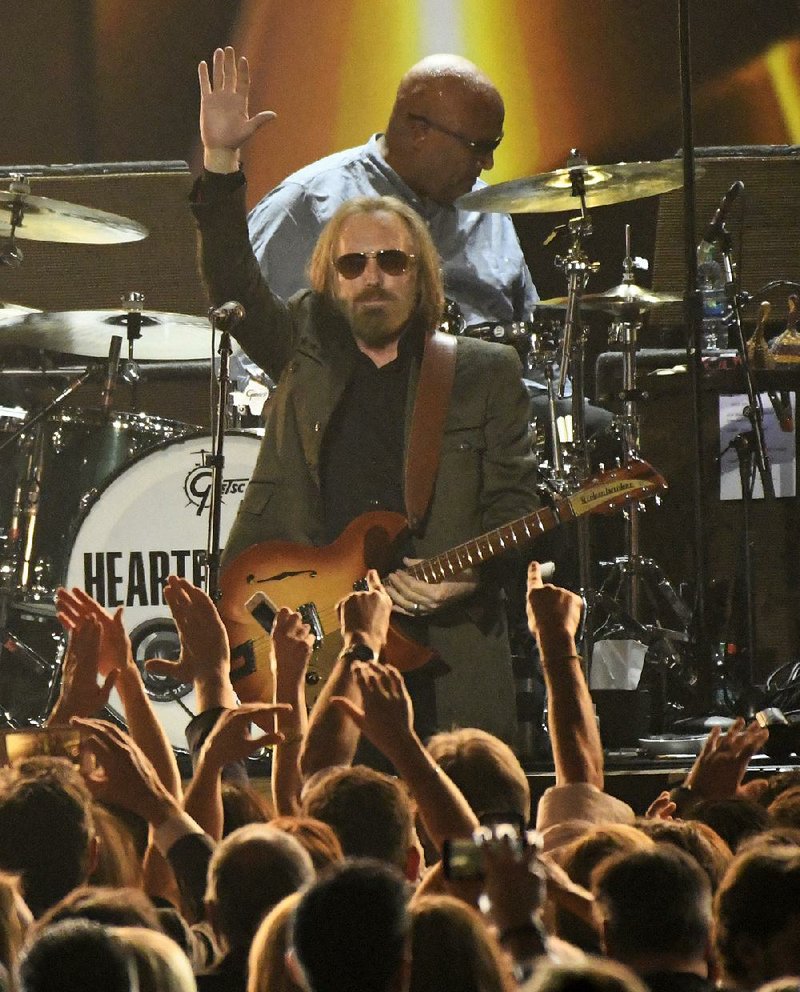

For me, the joke worked even better if the name used was "Tom Petty."

But then Oct. 2 the saddest thing happened. There was a horrible massacre in Las Vegas. And Tom Petty died.

Guess which affected me more.

Maybe I should feel some shame about that, because every human life matters. But our world is a killing field, and random madness and malign neglect kill thousands every day. Bombs go off in parts of the world we never consider; we inure ourselves to violence inflicted on other people's children in other parts of town. Intellectually we can feel bad about the murder of strangers, but we have to remind ourselves to think about their suffering. We shake our heads and move on, fire up the second season of Stranger Things and forget that there are sad things in the world.

So why, more than a month later, are so many of us still sad about Tom Petty?

Well, sociologists will tell you it's because we do have a relationship with the public people to whom we pay attention. In 1956, social scientists Donald Horton and R. Richard Wohl coined the term "parasocial interactions" to describe the "intimacy at a distance" fans feel with performers and artists. We don't know them, but they aren't strangers -- it's their job to connect with us, and the best and truest of them connect most deeply.

We don't know them, but we do know a part of them. We know their work and the persona that presents the work (which can be as, or even more important, than the work itself). As best as I can remember, I never met Tom Petty and never spoke with him on the phone. But I connected with that grinning gaunt scarecrow with the lank corn-silk hair raking big open crystalline chords from a Rickenbacker 625-12. (That's the model he's holding on cover of Damn the Torpedoes. It was actually his Heartbreakers band mate Mike Campbell's instrument -- and I've always wanted one.)

We were born at opposite ends of the same decade, in the same part of the country. At first, Petty's Southernness didn't seem to matter. We perceived his first album -- Tom Petty and the Heartbreakers, which came out just as I was starting to review records and to occasionally play my own songs in bars -- as almost punk, a sort of sneer-y, skinny-tied New Wave blast with just a bit of that Byrds-ian jangle breaking through. Looking back, you could say that outside of "Breakdown" and "American Girl," the songwriting is fairly ordinary, but the energy and swagger -- the immersion in the noisy possibilities of rock 'n' roll -- felt redemptive.

Petty wasn't a deep songwriter, he mostly mined the rich if whiny adenoidal vein of post-adolescent romance. He mostly employed a playful snarl. He mostly sang about girls.

Maybe at the time I noticed the vocal resemblance to Roger McGuinn, but the sonic reference I picked out was Elvis Costello, whose Attractions, at the time, seemed as important to the overall effect as Petty's Heartbreakers.

Man, I loved those first three records; and even today, when I recognize Petty was one artist who was best served by greatest hits compilations, I can't help but be swept up in nostalgia for those backward-looking albums. In a way he was my Elvis Presley, and now I know why grown-ups cried on Aug. 16, 1977; why Don McLean wrote "American Pie" about Buddy Holly.

You can't frame Petty's dying as a tragedy; he wasn't young and he wasn't thwarted -- he even acquired a little gravitas to go with his fortune. He probably had himself a pretty good time.

But yeah, it's hard to think about not hearing a new record (although there probably will be a new record, there always seems to be plenty of material to release posthumously). Harder to think about never going to another Tom Petty show.

That feels weird, because I don't go to a lot of shows anymore, and I probably wouldn't have made any special effort to see Petty and the Heartbreakers anyway. But most of us don't think about the things we're never going to do again.

And that's the thing that stings, isn't it? The real crux of the thing: when we grieve for people we've never met, what we're really doing is contemplating our own certain mortality -- the impossible idea that there will be a last time for everything. A last time to kiss your mother, to look your father in the eye. A last time to walk to the grocery store.

All grief is frivolous and vain; but the deaths of artists and celebrities are like mile markers on our own road to nowhere. David Bowie, Leonard Cohen, Lou Reed -- it feels like something ending. Because it is.

"It is the blight that man was born for," poet Gerald Manley Hopkins wrote in "Spring and Fall."

It is ourselves we mourn for.

Email:

blooddirtangels.com

Style on 11/05/2017