ALEPPO, Syria -- Her face was ashen, her solemn manner suggesting a state of grief.

"It is as though we lost a close relative," Haymen Rifai, 60, explained gravely as she stood with her two daughters in the war-pulverized center of Aleppo. "Each time we come here it feels worse."

She had not lost a loved one, but rather a cherished, stone-and-mortar symbol: the historic Umayyad mosque, which Rifai and her family had arrived to visit on this sun-drenched afternoon -- part of a daily, if forlorn, pilgrimage to the grievously wounded house of worship in the heart of the Old City.

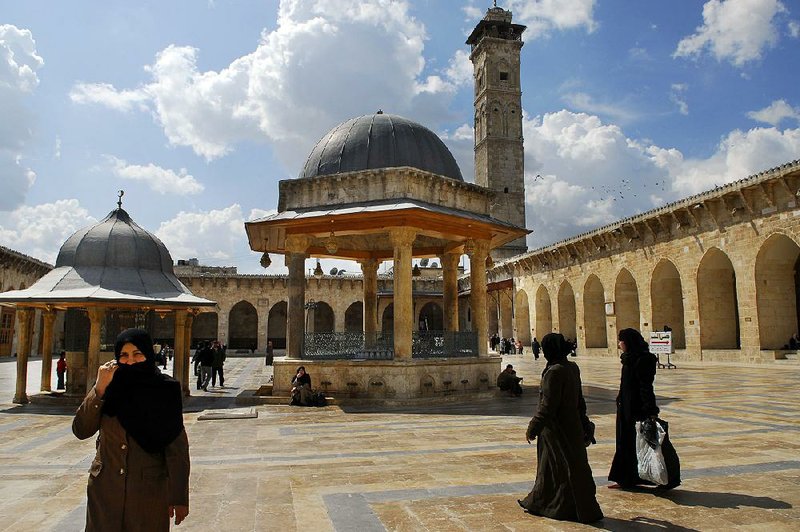

Another visitor, Mohammed Marsi, 41, and his son surveyed the vast courtyard once distinguished by intricate geometric designs in alternating black and white stones. Now the stones are chipped or shattered, or hidden by mud or implements of war.

"The destruction for the whole country is indescribable, just like what happened to the mosque," said Marsi. "If you knew the mosque before the damage, and saw it now, it is like someone who lost a child or part of his body."

The sublime mosque, along with the nearby, medieval-era covered souk, have long been synonymous with Aleppo, the core of which the United Nations declared a World Heritage site.

The mosque and the souk, along with much of the Old City, suffered calamitous harm during the more than four years that this former Silk Road hub was divided between opposition fighters and forces loyal to the government of President Bashar Assad.

The mosque, souk and adjoining districts were transformed into World War I-style front lines, featuring trenches lined with sandbags, fortified tunnels, sniper emplacements and near-daily shelling.

The mosque, once a pillar of Syria's moderate Sunni Muslim establishment, became a kind of opposition command center, hosting jihadi luminaries such as the firebrand al-Qaida-linked Saudi cleric Abdullah Muhaysini, who gave YouTube interviews from the stately courtyard.

Construction on the earliest mosque on the site began in 715, and through the centuries the complex has been rebuilt and renovated again and again after earthquakes and fires, looting and war. The mosque's signature minaret, nearly 150 feet tall, had survived since 1090.

But in April 2013, clashes reduced the minaret to a pile of rubble and collapsed the mosque complex's northwestern wall. The rebels blamed Syrian forces. Syria blamed the rebels.

But the huge scale of destruction began to become clear to the outside world only in December. That's when opposition fighters and their supporters finally decamped from their last strongholds in the city after months of government bombardment.

Since then, thousands of Aleppo residents who fled have returned from their places of exile. For many returnees, among the first stops has been the Old City and the beloved Umayyad mosque. Visiting has become a rite of passage for individuals and families.

"This is the first time for me to come to the mosque since the war, and I was really shocked," said Soha Alkhatib, 54. "I saw a lot of pictures of the mosque on the Internet, but I didn't expect to see this amount of damage. There are no words that can describe my sadness, my pain."

Though cleanup efforts have been underway for months, its walls remain riddled with bullet holes and pocked with shrapnel. Sandbags and 55-gallon drums filled with dirt mark where opposition fighters dug in against relentless government bombardment. Bullets and blasts have damaged some of the regal interior chandeliers, though many remain intact.

A pair of washing or ablution fountains in the courtyard still stand but are shot through and through. Gouges from bullets and shells mar the elegant porticoes and grand wooden front doors.

Still, the people come. And still, it is their mosque.

"I have always visited this mosque, its feel, its smell -- it is the essence of Aleppo," said Abdullah Bayoud, 56, a truck driver who was among the many stopping to pray at the walled-off shrine inside the mosque that in Islamic belief is said to contain a relic of Zacarias, a prophet and father of John the Baptist.

"Zacarias is the protector of Aleppo," said Bayoud, a father of seven who, like so many others, fled his home during the fighting. "He is with our city."

Both the mosque and the souk, shielded by stone walls at times more than 3 feet thick, appear structurally sound, despite the immense damage. But restoration is a huge undertaking that will take years, officials say, and cost many millions of dollars. Full repair will probably await the end of a war now into its seventh year.

Although Aleppo is now firmly in government hands, rebels remain dug in just west of the city, still within shelling range of various neighborhoods. Ambulances regularly screech through the streets with war victims.

The citizens of Aleppo, however, point out that their august city -- called Halab in Arabic and regarded as one of the longest continuously inhabited areas on Earth -- has rebounded from previous calamities, including 13th century Mongol sackings. And there are many signs of recovery.

Schoolchildren now scamper about the esplanade of the nearby Citadel, a medieval fortress that remained in government hands throughout the war. Notices posted outside the walls advise visitors to watch out for unexploded grenades and mortar shells. Other signs proclaim "Welcome Back" in English and Arabic, and plug a government-backed social media campaign.

Meantime, the people of Aleppo, and visitors, inevitably make their way to Umayyad mosque to say a prayer, contemplate its splendor, its history and its near-ruin, or just reconnect with one of the region's iconic sites.

Among those paying their respects one April day was Syria's chief Sunni cleric, or grand mufti, Ahmed Badr Din Hassoun, who had earlier hailed the government's recapture of "the crown of Aleppo." The mufti, a key ally of the Assad government and long a would-be target of opposition assassins, arrived in a convoy of more than a dozen vehicles, mostly ferrying heavily armed bodyguards.

Another recent visitor was Eva Jabbour, her presence a reminder that the mosque's majesty, even now, transcends sectarian lines. She is Christian.

"This place is so important for all people of Aleppo, whatever their belief or sect," said Jabbour, 60. "It is here for all of us. Our most profound hope is that the Great Mosque will be rebuilt, and be even better than it was before."

Also stopping by were a pair of towering Russian soldiers, part of a substantial force backing Assad's government. Upon exiting, one showed his respect for the ravaged house of worship in the best way he knew how.

He made the sign of the cross.

Information for this article was contributed by Liliana Nieto del Rio of the Los Angeles Times.

SundayMonday on 05/21/2017