Capital punishment in the United States is slowly and steadily declining, a fact most visible in the plummeting number of death penalties carried out each year. In 1999, the country executed 98 inmates, a modern record for a single year. In 2016, there were 20 executions nationwide, the lowest annual total in a quarter-century.

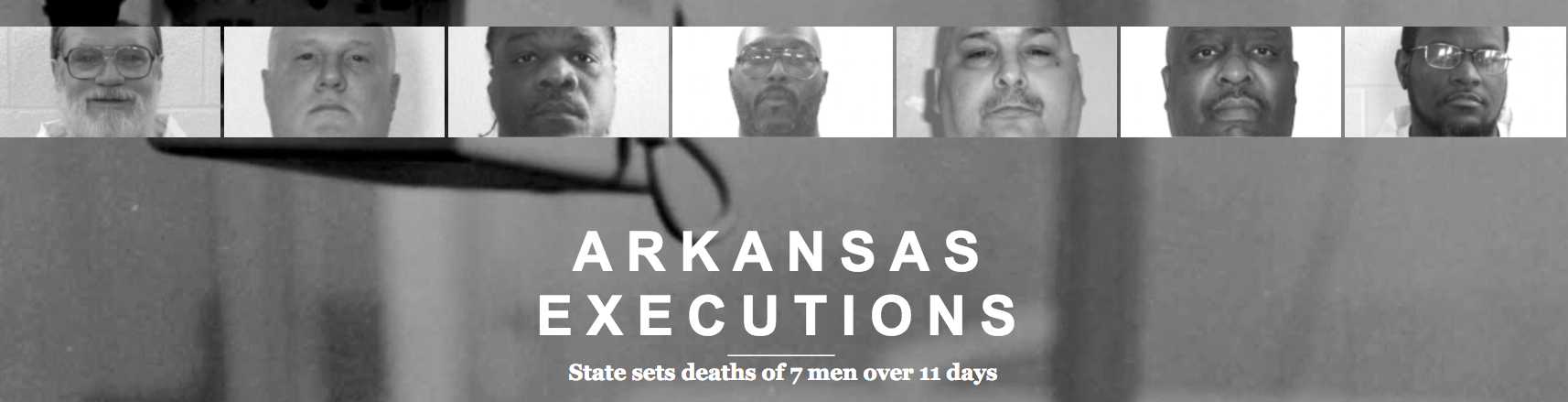

EXECUTIONS: In-depth look at 4 men put to death in April + 3 others whose executions were stayed

Click here for larger versions

Death sentences also sharply declined. Fewer states that have the death penalty as a sentencing option are carrying out executions, a trend that has continued despite two U.S. Supreme Court rulings in the past decade upholding lethal-injection practices. States that would otherwise carry out executions have found themselves stymied by court orders, other legal uncertainty, logistical issues or an ongoing shortage of deadly drugs. Fewer states have it on the books than did a decade ago, and some that do retain the practice have declared moratoriums or otherwise stopped executions without formally declaring an outright ban.

Public opinion also has shifted. A Pew Research Center survey last year found that for the first time in almost half a century, public support for the death penalty dipped below 50 percent; other polls found slightly higher support, but the overall numbers remained considerably down from the mid-1990s, when 4 out of 5 Americans backed capital punishment.

Another way to see the changing nature of the American death penalty: The gradual decline of death-row populations. At the death penalty's modern peak around the turn of the century, death rows housed more than 3,500 inmates. That number is falling, and it has been falling for some time. New Justice Department data show that death-row populations shrank in 2015, marking the 15th-consecutive year with a decline.

There were 2,881 inmates on state and federal death rows in 2015, the last year for which the Justice Department has nationwide data available. That was down 61 from the year before.

States carried out 28 executions in 2015, but nearly three times as many inmates -- 82 -- were removed from death rows "by means other than execution," the Justice Department's report states. Another 49 inmates arrived on death row that year.

In some cases, inmates left death row after being cleared of the crimes for which they were sentenced. Five people sentenced to death were exonerated in 2015, according to the National Registry of Exonerations, a project of the University of Michigan Law School and the Northwestern University School of Law.

Other inmates died before their executions could occur. In Alabama, three inmates died of natural causes in 2015 and a fourth hanged himself that year inside a prison infirmary, according to corrections officials and Alabama media reports. North Carolina officials say one death-row inmate died of natural causes that year, another was resentenced to life without parole and a third had his death sentence vacated and a new trial ordered.

Death sentences were thrown out in some cases. Four death-row inmates in Maryland had their sentences commuted to life in prison without parole in 2015, a decision made by then-Gov. Martin O'Malley after that state formally abolished the death penalty.

Meanwhile the number of people sentenced to life in prison has ballooned, reaching an all-time high last year, according to a report released last week from the Sentencing Project. The report states that more than 161,000 people were serving life sentences last year, with another 44,000 people serving what are called "virtual life sentences," defined as long-term imprisonment effectively extending through the end of a person's life. Similar to overall prison populations, black people are disproportionately represented; they account for nearly half of the life or virtual-life sentences tallied in the report.

The time between a death sentence being handed down and carried out has grown significantly. In 2001, when the American death penalty was at its apex with 3,500 prisoners on death row, they were spending an average of 8.6 years there after receiving their sentence, according to federal data. By 2013, the last year for which full Justice Department data are available, the death-row population fell below 3,000 while their time there ballooned to an average of 14.6 years.

Timeliness was an issue last month when Arkansas was seeking to carry out its first execution since 2005 -- one of eight originally planned for April. An inmate named Ledell Lee, 51, was sentenced to die for the killing of Debra Reese, who was beaten to death in her home in 1993. Lee, who had long denied any involvement in her death, sought DNA testing to prove his innocence. His attorneys appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court for a stay, but in a 5-4 decision, the justices sided with the state and denied the request.

Dissenting from that decision, Justice Stephen Breyer questioned Arkansas and its schedule of executions.

"Why now?" he wrote. "The apparent reason has nothing to do with the heinousness of their crimes or with the presence (or absence) of mitigating behavior. It has nothing to do with their mental state. It has nothing to do with the need for speedy punishment. Four have been on death row for over 20 years. All have been housed in solitary confinement for at least 10 years. Apparently the reason the state decided to proceed with these eight executions is that the 'use by' date of the state's execution drug is about to expire."

Lee was executed that night, becoming the first of four inmates put to death in Arkansas in a span of eight days. Courts blocked the other four executions that had been planned. According to the state, one of the three drugs used in lethal injections there expired last week, and because of the ongoing shortage, officials have said they are unclear when more can be obtained. Arkansas currently has no other executions scheduled.

A Section on 05/07/2017