First in a series

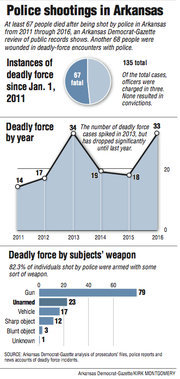

Police in Arkansas shot at least 135 people in the past six years. Sixty-seven died.

During the same period, at least three Arkansas police officers were fatally shot by assailants, and 31 reported being shot at when they wounded or killed someone, according to research by the Arkansas Democrat-Gazette.

Those numbers come from the Democrat-Gazette's efforts to count all deadly-force encounters -- fatal or not -- between the public and law enforcement from 2011-16.

The newspaper built a database from public records and media reports because reliable, official statistics on police shootings are hard to come by.

The lack of official numbers makes it difficult for police to do their jobs, and breeds mistrust and suspicion among the public, say social scientists, political leaders and law enforcement officials.

And while few deadly police encounters in Arkansas resulted in the protests or public outrage seen elsewhere, that doesn't mean it couldn't happen, Little Rock Police Chief Kenton Buckner said.

"Have you ever heard of Falcon Heights?" Buckner asked, referring to the Minnesota town where a police officer killed school lunchroom worker Philando Castile in July.

"You'd never heard of it, had you?" the chief said. "So, if it can happen in Falcon Heights, Minnesota, it can happen in Little Rock, Arkansas."

The Democrat-Gazette developed this series of articles by analyzing thousands of pages of documents obtained through dozens of public records requests. The newspaper also used media reports to fill in gaps in the official records.

Among the newspaper's findings:

• Black men make up 7.5 percent of the state's population. They accounted for more than 39 percent of people police killed or wounded from 2011 to 2016.

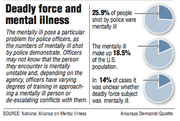

• A quarter of all victims of officer-involved shootings -- at least 35 cases -- struggled with mental disorders. Officers in those encounters often had failed to complete training that would help them interact with the mentally ill.

• Police investigations into deadly-force encounters often lacked impartial oversight and rarely resulted in actions against the officers who fired their weapons.

• The people killed by police included one woman. The rest were men -- black, white and Hispanic, armed and unarmed, ranging in age from 15 to 107.

• Last year, Arkansas police used deadly force 33 times -- a 68 percent increase from the six-year average.

• So far this year, five people have been shot by police, two fatally.

Incomplete or imprecise record-keeping by certain law enforcement agencies and prosecutors means some lethal-force incidents may have been overlooked.

Most prosecutors said they didn't have indexes on deadly-force investigative files and could furnish only the files that they remembered handling.

First Judicial District Prosecuting Attorney Fletcher Long refused to dig up the files the newspaper requested under the state Freedom of Information Act. The 1st Judicial District covers Cross, Woodruff, St. Francis, Monroe, Lee and Phillips counties.

"I would have to go through each and every file maintained in my office to see if they had anything to do with the use of police force," Long emailed in response to the newspaper's request. "I decline to do this."

Andy Riner, 18th-West Judicial District prosecutor, didn't release deadly-force case files when the newspaper first requested them in July; he said he considered them homicide investigations with no statutes of limitation.

"If additional information were to be obtained in these matters, we may reopen the investigative process," Riner said in a letter.

The state public records law exempts details of active investigations from disclosure.

Months later, Riner released some of his files after the newspaper questioned his interpretation of the law. He said he was still searching for other records, which weren't provided before publication of this series. Riner's district covers Polk and Montgomery counties.

Eight of the state's remaining 26 elected prosecutors provided only one- or two-page cover letters rather than complete case files.

Information shortage

Like Arkansas, other states and the federal government fail to effectively track lethal-force cases, making any comparison difficult.

For now, the most complete public data on police shootings have been compiled by media outlets. The British newspaper The Guardian and The Washington Post began compiling comprehensive lists of people killed by police in 2015.

A 2015 investigation by the Post and Courier, a Charleston, S.C.-based newspaper, found that South Carolina police engaged in deadly force 235 times over a 77-month period -- roughly one occurrence every 10 days.

The Democrat-Gazette examined a 72-month period and found 135 cases, almost one every two weeks.

Adjusted for population, police in both states used lethal force at almost identical rates.

The FBI claims to track police-caused deaths and serves as a clearinghouse for crime statistics from all 50 states.

But at a crime summit in September, even FBI Director James Comey admitted the agency's collection methods are flawed and described the lack of data on police-involved shootings as "embarrassing" and "ridiculous."

The FBI's statistics, for example, showed that Arkansas law enforcement officers have killed two people since 2011. The Democrat-Gazette's data show that police in the state killed twice that many people in December alone.

Under former President Barack Obama's administration, the Department of Justice began to "re-design" how it tallies police-caused deaths by scouring media reports before inquiring with individual police departments and coroner's offices for verification and additional details.

In December, the Justice Department released a preliminary report of the redesign -- which counted shootings between 2015 and 2016 -- and estimated that FBI statistics covered only about half of the actual deaths.

That report matched the Democrat-Gazette's count of one officer-involved shooting death in the state from June 1 to Aug. 31, 2015, but it didn't include four other nonfatal shootings by Arkansas police.

'They're humans'

Local police agencies often track use of force within their departments to steer training and policy, but some officials say the absence of large-scale data is problematic.

"I think every modern police agency recognizes the vital importance of transparency," said Hope Police Chief J.R. Wilson, immediate past president of the Arkansas Association of Chiefs of Police.

"Scrutiny does make policing better. Scrutiny ensures that justice remains fair and equitable for all in a dynamic and imperfect environment.

"But, we must be careful," he said. "A vigilante or politically expedient approach to perceived injustice without reasonable understanding of the facts of an incident is unreasonable, unconscionable and not acceptable."

Many officers say that the heightened scrutiny they face has made their jobs harder.

In a nationwide survey released in January, police reported that the attention surrounding high-profile fatal shootings increased tensions between police and blacks, and made officers less willing to stop and question suspicious people.

The findings of the Pew Research Center survey included attitudes and experiences drawn from almost 8,000 police officers belonging to departments of 100 or more officers.

The report shows that police and the public disagree over the causes of police shootings and that police don't always agree with each other on that issue.

Sixty-seven percent of officers surveyed described the killing of black Americans in police encounters as "isolated incidents," while 60 percent of the public reported that these shootings were "signs of a broader problem."

The survey also noted differences in the views of black and white police: 92 percent of white officers said the country has already made the changes "needed to give blacks equal rights," while 69 percent of black officers said more needed to be done to ensure that blacks are afforded "equal rights with whites."

A large majority of officers surveyed also said they thought the public "doesn't understand the risks [police] face."

In many of the cases reviewed by the Democrat-Gazette, police had just seconds to weigh life-or-death decisions.

Since 2011, three officers in the state have been shot dead, two officers were killed in vehicular assaults, and two prison guards were killed by inmates.

"Officers are operating in an environment now that they didn't used to operate when I was just starting," said 23rd Judicial District prosecutor Chuck Graham.

"Officers have been shot for no other reason than they were a police officer. How do they operate in that? They're humans."

Graham was president of the Arkansas Prosecuting Attorneys Association last year and has decades of law enforcement experience with the U.S. Air Force.

"You're not the one that has a gun pointed at you," he said. "You're not the one that's having to make a decision like that."

Arkansas prosecutors charged police with crimes in only two of the 135 cases the newspaper reviewed, but neither officer was convicted at trial.

Prosecutors across the United States have struggled to successfully try cases against police officers -- a trend law experts attribute to juries' predisposed leniency toward police.

Overall, 2016 was different for prosecutors than previous years.

Nationally, at least four officers were convicted by state-court juries for on-duty shootings as compared with 2014 and 2015, when no officers in the United States were found guilty on murder charges, according to Philip Stinson, a criminal justice professor at Bowling Green State University in Ohio.

Stinson worked for police departments in Virginia and New Hampshire before earning advanced degrees in law and criminology. In 2005, he started collecting data on police shootings -- which are frequently cited by researchers and media outlets -- by sifting through media reports, court records and videos.

Thirteen officers were convicted of murder or manslaughter for deadly on-duty shootings between 2005 and 2015, Stinson's research shows.

This does not include cases in which officers faced lesser charges.

In cases reviewed by the Democrat-Gazette, local police officers involved in shootings generally were granted special concessions, such as extra time to prepare their statements to investigators.

Often, the officers who fired their weapons were questioned by their colleagues -- a potential conflict of interest, say survivors and legal experts.

These practices have created a feeling of helplessness in victims' families -- families like the Finleys.

'The last thing'

As he stands in a cold October drizzle, Chris Finley recounts the worst night of his life -- the night his son Grant died at the hands of a Jonesboro cop.

Finley slowly turns a brass shell casing between thumb and forefinger, and points to the spot where his 31-year-old son took his final breath.

The night Grant Finley died, his father cleaned up the pool of his son's blood left behind by crime scene investigators -- and found the .40-caliber shell casing now wheeling in his hand.

"This didn't have to happen," Chris Finley says.

Grant Finley was typical of mentally ill individuals whose interactions with police led to injury or death from officers who had little or no training in calming agitated, confused people.

His family knows he wasn't perfect. His schizophrenia, and use of legal and illegal drugs to deal with his troubles led to several run-ins with police.

And while his father and sister acknowledge that he shouldn't have brandished a machete the night he was killed, they also say the officer shouldn't have shot him. The officer was not charged.

The Finleys and other victims' families feel the system intended to protect them has done the opposite.

"I feel like the last thing you want to do is call the police for help," said Caitlyn Finley, Grant's sister.

"I don't want to deal with them unless I have to, and that's sad. They should be the first person you want to call if you're in trouble."

Some families seek justice through the federal courts.

Thirteen separate federal lawsuits have been filed so far involving the cases reviewed by the Democrat-Gazette. More than a million dollars in settlements have gone to some families, court records show.

'A lot of anecdotes'

Some Arkansas lawmakers are pushing changes this year to alter the way police shootings are tracked.

Their intent is to give lawmakers and police the information needed to have an "educated discussion."

Rep. Vivian Flowers, D-Pine Bluff, filed a shell bill last week "to establish a uniform standard for data collection among law enforcement agencies." In a phone interview, she said that would encompass officer-involved shootings. She added that she is working with the Commission on Law Enforcement Standards and Training to sort out how to effectively record the data.

Some lawmakers, though, worry that their colleagues will be hesitant to support a bill that receives push-back from the law enforcement community.

"When we talk about tracking this, we start moving into corners right away," said Sen. Joyce Elliott, D-Little Rock.

"Officers feel accused, but it's not accusatory at all. We have a lot of anecdotes. But if we had data, that would tell us if those anecdotes are trends," she said.

Elliott filed a shell bill in the 2015 legislative session that called for creating a statewide "citizen's review board on policing practices" aimed at promoting "positive relationships" between law enforcement and communities, and providing for fair and transparent police practices. The bill did not contain any details and wasn't pushed further.

Legislatures in eight other states have passed laws requiring the collection of data on police use of deadly force. But most of those laws are new and haven't been as effective as intended, according to studies and news reports.

The central problem is that police agencies often fail to report use-of-force encounters and aren't penalized, according to officials in those states.

In Texas, for example, a public database debuted this year, but it was missing several notable instances of use of force. State officials have said it will take time for all agencies in the state to grow accustomed to reporting fatal force encounters.

In Maine, the state's attorney general reviews all deadly force investigations and posts the reviews online. But there is no collective data set that would identify trends, which could then be addressed through policy.

As for Arkansas, James Golden, a criminal justice professor at the University of Arkansas at Little Rock, believes more data would be helpful, but he doubts steps will be taken to collect that information anytime soon.

"More data is always good," said Golden, a former Jonesboro police officer. "However, nobody is ever willing to pony up the money."

A final embrace

At 9 p.m., April 4, 2015, Jonesboro police confronted Grant Finley about an earlier altercation with a woman at his home, but he refused to answer the door.

Chris Finley persuaded officers to allow him to take his son to the police station early the next morning. The officers agreed and left 30 minutes later.

Or so the Finleys thought.

At 10:50 p.m. Chris Finley wrapped his son in a tight hug and whispered good night, unaware it would be their final embrace.

Meanwhile, officer Heath Loggains waited behind bushes across the street. Through the leaves, he saw Chris and Chris' daughter drive away in a white pickup.

Loggains later told investigators that he and several other officers took it upon themselves to stake out Grant Finley's home, believing he would hurt others or himself.

Loggains' statements to detectives tell what happened next:

About 11:40 p.m., Grant Finley stepped onto his front yard, in socks and camouflage pants. A machete sheath hung from his belt.

Loggains jumped from behind the bushes, barking commands.

Grant retreated into his tiny home and shut the metal door.

The officer kicked the door several times trying to get inside.

The door jamb abruptly gave way. The two men pushed against the door from opposing sides.

Losing ground to Loggains, Grant swung the blunt end of the machete through the space between the jamb and the door.

Loggains stepped back and unholstered his gun.

Fourteen bullets punched through the thin metal door.

For two hours, police reports show, a tactical team waited outside, unsure of whether it was safe to enter. Finally, they pushed a pole camera through the front window of the small home.

The camera screen showed Grant, with streaks of blood staining his chest, slumped against the door, dead.

SundayMonday on 03/12/2017