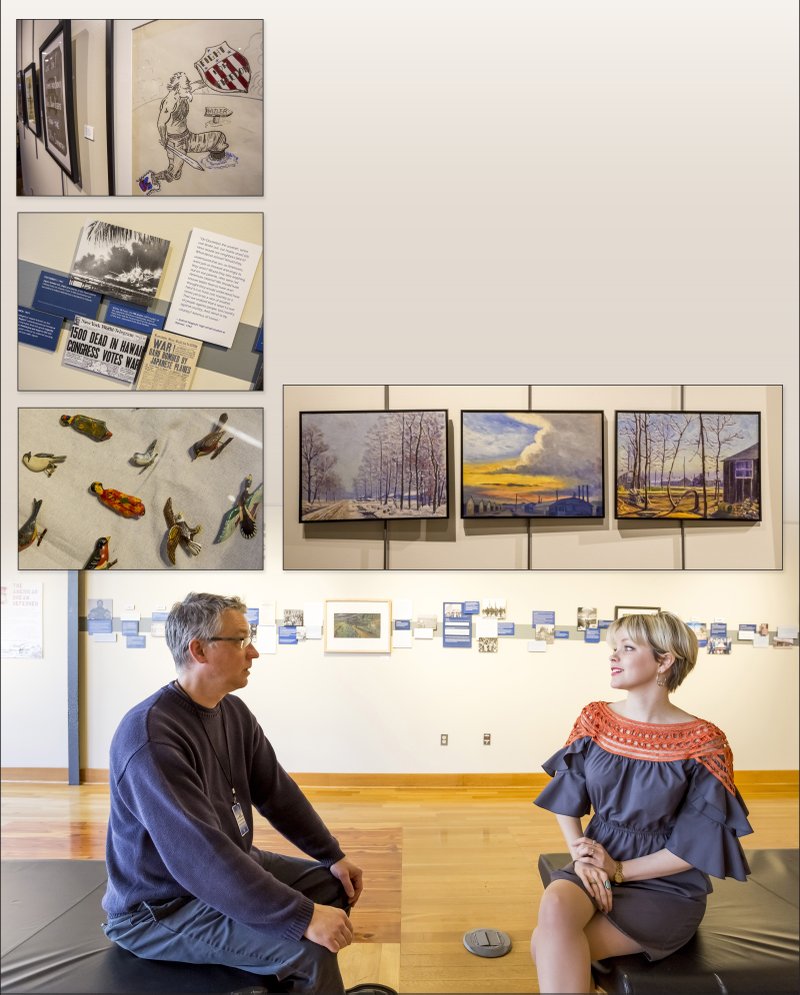

A little flock of bird pins, delicately carved and painted in vivid colors, rests in a glass case. Pins like these, inspired by the popular Audubon bird print series, were all the rage in the 1940s.

But these particular birds represent much more than a fashion trend.

“The American Dream Deferred: Japanese American Incarceration in WWII Arkansas”

Through June 24, The Butler Center for Arkansas Studies, 401 President Clinton Ave., Little Rock

Hours: 9 a.m.-6 p.m. Monday-Saturday

Admission: free

Info: (501) 320-5790

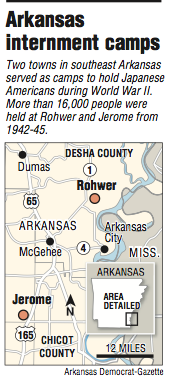

These birds were made by inmates at the Rohwer War Relocation Center, a detention facility for Japanese Americans that operated from 1942 to 1945 in Desha County in southeast Arkansas. Now they're a part of the collection at Little Rock's Butler Center for Arkansas Studies and its newest exhibit: "The American Dream Deferred: Japanese American Incarceration in WWII Arkansas." It is the first of four exhibitions about the Japanese internment in Arkansas that will be held at the Butler Center over the next two years.

Because the inmates couldn't get jewelry in the camp, "all of these bird pins are made out of scraps," says exhibition curator Kim Sanders.

She points out how the legs were made from wires pulled out of screen doors.

The art created at Rohwer and at Jerome War Relocation Center in Drew and Chicot counties gives impressive and poignant insight into what the 16,000 inmates' lives were like the years they lived there.

This is not the first time the Butler Center has had an exhibit on the subject, but this is its largest and most involved effort: a four-part, two-year project that will focus on multiple aspects of the history and cultural significance of the Japanese American experience during World War II. The exhibit exists thanks in large part to a grant from the National Park Service to encourage spreading the story of Rohwer and Jerome.

The efforts of people like actor George Takei, who lived at Rohwer and the Tule Lake facility in California as a child, have drawn more attention to the story of Japanese Americans' forced relocations, a story that has been

largely unheard for many years.

"It's only been in the past couple of decades that this story has gained momentum," Sanders says. "For a while, it was swept under the rug. People didn't talk about it."

The 1941 attack on Pearl Harbor fanned strong anti-Japanese sentiments and fears of further Japanese attacks on the United States. In response, President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066, ordering the deportation and internment of thousands of people of Japanese descent, most of whom were American citizens and most of whom lived in California, Oregon and Washington state.

Many were gathered in places like the Santa Anita racetrack, where horse stables were converted into "apartments," before the people were loaded on trains and sent to camps. They worked, went to school, took classes, took part in camp government, had clubs and social events, but they were also surrounded by barbed wire and guards and forced away from their homes and livelihoods.

...

The Butler Center has a large collection of artifacts, particularly from Rohwer, that includes art, furniture, camp school yearbooks, newsletters, posters, circulars, even mundane things such as art supply lists.

Much of that is due to the foresight and dedication of Mabel "Jamie" Jamison Vogel, the art teacher at Rohwer, who saved everything she could think of. When she died, she left her collection to Rosalie Santine Gould, the mayor of McGehee, who eventually donated everything to the Butler Center.

It was a perfect fit, Butler Center Director David Stricklin says. There are five galleries for displaying art, but also a research room that's open to the general public.

"You could go up there right now and sit down and read. We're unusual in that respect."

As word has gotten around about the collection, more and more people have donated pieces because, as Stricklin explains, they realize that having such an extensive collection in one place "attracts people to come learn about it and experience it."

One person who donated works to the collection is Frank Sata (named for President Franklin Roosevelt), whose father, J.T. Sata, was an accomplished and established artist before his incarceration at Jerome. The new exhibit features a few of his paintings of the Jerome camp and one of his sketchbooks. They were some of the last pieces Sata ever did.

"As a result of the whole experience, he stopped creating art," Stricklin says. "It was so jarring for him he couldn't do it anymore."

The exhibit is organized thematically. Along one wall, there's a timeline that covers the story of the Japanese in America from the 19th century to the 21st, with a heavy emphasis on WWII. The historical data is interspersed with photos and artwork and excerpts from autobiographies by Rohwer high school students who were asked to write about their experiences so far.

The artwork is divided into sections. There's a section on Vogel, with her portrait and photos of her students posing by the mural they painted on the walls of the camp gym, and displays on Rohwer and Jerome.

The wall on community focuses on the various activities and interests people had, like a series of fashion sketches.

"A lot of what the people in the camps tried to make life as normal as possible," Stricklin says. "So some of the young women, especially, they would design dresses because that's what they had been interested in."

They also kept up with more traditional Japanese art like kobu (a process of boiling, removing bark from and polishing cypress knees) and there are a few examples on display.

"Part of it goes back to this Japanese aesthetic of loving natural forms, simple things and things that are imperfect," Sanders says.

Nearby, the identity wall has sketches and paintings that represent the cultural duality these people felt -- the pull between their dedication to and love for America and the pride and strength of their Japanese heritage.

"For a lot of them, it was a real struggle with their identity," Sanders says. "You can be 100 percent American and have a different heritage. We know that now, but back then that was a different story."

That duality also comes into stark relief in the wall of patriotic posters, all painted in the camp and all looking very much like posters that could be found all over the country. Calls to "Keep Them Flying" or to buy war bonds. Despite the fact that they were called "resident non-aliens" instead of "citizens" and that they had been taken from their homes, many of them were still very patriotic.

Sanders says, "It's no different in these camps, even though they were rounded up by the very government they're trying to support, they still want to show they're loyal Americans so they were going to do their part for the war effort."

About 800 Rohwer camp inmates ended up serving in the 442nd combat team in Europe, which may have been the most highly decorated military unit in the war.

"Their attitude was, I think, the faster the war ends, the faster we can go back to California," Stricklin says.

The residents had access to ample amounts of wood, since Japanese American labor was used to clear the swamps for farmland.

Much of that wood was used to make furniture. The government provided inmates with a pot-bellied stove, a cot and a mattress. To make their little barrack apartments less stark, residents made their own furniture, built front porches, added gardens and gazebos. The exhibit includes a chair, table and screen made from pieces of scrap wood.

While Sata's paintings and some other pieces are obviously by skilled, highly trained artists, Sanders says, "Most of the work that we have here is by people who had never done art before."

Art classes were very popular at the camps with adults and children and while they did have some art supplies to work with and they could order fabric to make clothes, they also created art out of whatever they could find -- like making carefully sewn necklaces out of metal buttons.

"The ingenuity in this whole collection -- the whole experience is just incredible," Sanders says. "It's a testament to how humans can endure. They usually turn to art for endurance. It gives them some sort of control, I think, over their surroundings when they have little control otherwise."

...

This particular exhibit will continue at the Butler Center through June 24, but there will be three more. In the fall, there will be an exhibit of photographs by Paul Faris, who was invited to the camp to photograph the residents.

Part three, in winter/spring 2018, will focus on the experiences of the camp high school students, giving more details from the students' autobiographies, artworks and yearbooks.

The final part, in later 2018, will be on camp portraits.

The current exhibit will stay in a state of flux.

"Things are going to change," says co-curator Colin Thompson. "What you see here is just the beginning."

They plan to continue to add more pieces of artwork from the permanent collection, so Thompson promises there will be different things to see as weeks go by.

The national attention drawn to the story of Japanese Americans in WWII has increased over the years, and so has interest in the Butler Center's collection.

Takei has come to visit and explore the art and documents. While they have not interviewed him, they have started collecting interviews with other former inmates, their families and the relatives of people who worked at the camps. And they have hopes for starting new research projects based on the documents and works in the collection.

But it's still a subject many people don't know about. Even if they do know about the internment camps in general, there are still many who don't realize there were two in Arkansas. That's what the exhibit hopes to correct: to let people know what happened in southeast Arkansas and to link past and present.

"Part of what I've tried to do here was try to relate it to people today," Sanders says. "I try to drive it home that it's really up to us to reshape society so something like this doesn't happen again."

That connection between past and present comes through in the first-person accounts of the students, or in a young woman's sketches designing her dream formal gown -- one that looks much like a dress from Gone With the Wind. It's a world away, but also so very normal.

"I want them to know that just because it's history doesn't mean it can't happen again," Sanders says. "History is a living, breathing thing. It's not just over. It's something we make happen every day."

Thompson agrees.

"It's a tremendous story. A very moving story. When you meet people who were in the camps and you see, this isn't just a random fact. These were real people that were in these camps in Arkansas. I think it's something people should know about."

Style on 01/29/2017