During my years as the political editor of this newspaper, I came to have great respect for state Sen. Stanley Russ of Conway. On my first day in a new job as the policy and communications director for incoming Gov. Mike Huckabee, my respect for Russ grew.

Ten minutes before he was to be sworn in as governor on July 15, 1996, Huckabee received a phone call from outgoing Gov. Jim Guy Tucker, who on May 28, 1996, had announced his intention to resign following a federal conviction on conspiracy and mail fraud charges. Tucker informed Huckabee that he had changed his mind, setting off a maelstrom that engulfed the Capitol until Tucker finally resigned unconditionally four hours later.

I was standing by Huckabee when the phone call from Tucker came in. The most important meeting that wild afternoon occurred in a former vault in the small office Huckabee had occupied since being elected lieutenant governor in a 1993 special election. During that meeting, Huckabee asked Russ, the Senate president pro tempore, and House Speaker Bobby Hogue of Jonesboro to lead efforts to impeach Tucker if Tucker didn't change his mind.

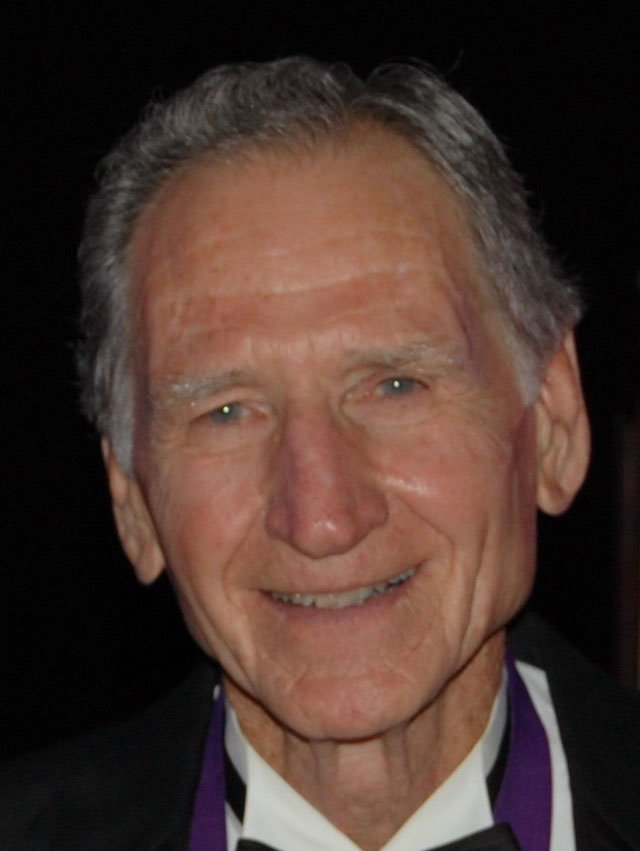

Huckabee was set to become only the third Republican governor since Reconstruction. Russ and Hogue, who at the time was hinting that he would run for governor in 1998, were Democrats. Russ, who died at 86 on Jan. 5 following a short bout with leukemia, didn't hesitate to let Huckabee know he had the senator's full support. Russ was an island of calm on a hot afternoon when calm people were in short supply at the Capitol.

During the 1997 legislative session, Russ stood up for Huckabee on numerous occasions as a faction led by state Sen. Nick Wilson of Pocahontas attempted to derail the governor at every turn. It was the Stanley Russ of July 15, 1996, and also the Stanley Russ of the 1997 legislative session that I thought about earlier this month when I heard of his death. But it also was the man who never missed a meeting of the Political Animals Club of Little Rock, of which I have served as chairman for the past six years, and the talented storyteller with whom my path often crossed at events across the state.

The story of how his 26-year Senate career began provides a fascinating look into the operations of what was known as the Old Guard in Arkansas politics. Russ first ran for the Senate in a 1975 special election to fill the vacancy left by Sen. Guy "Mutt" Jones of Conway, who had been convicted of income tax evasion and removed from the Senate. Jones, a Conway native who served almost 24 years in the Senate, once was described by the Arkansas Gazette as "the noisiest, newsiest, most ferocious, entertaining and controversial man in the Legislature." Veteran journalist Ernie Dumas wrote of him: "In the Senate, Jones would exhibit many idiosyncrasies, such as relaxing with his red cowboy boots propped on his desk. Each day, he brought a dozen red boutonnieres and ceremoniously pinned them on people he decided to favor--senators, Senate employees, the chaplain or reporters." Dumas went on to describe Jones as the Legislature's "most compelling orator and also its most partisan, craftiest and, some said, most vengeful member."

Another legendary Arkansas political figure of the era--Conway County Sheriff Marlin Hawkins--worked against Russ in his 1975 Senate race. Hawkins, who served in county office from 1941-79, was known across Arkansas despite being a county rather than a statewide official. The Encyclopedia of Arkansas History & Culture notes that he "managed to use his political friendships with various legislators and especially Gov. Orval Faubus" to bring projects to Conway County.

To understand Hawkins' strength in delivering votes in the county, consider this: Even though Winthrop Rockefeller lived in Conway County atop Petit Jean Mountain, he failed to carry the county against Democrat Jim Johnson when Rockefeller was elected governor in 1966 and failed to carry it again when he was re-elected in a race against Democrat Marion Crank in 1968. The Senate seat for which Russ was running included Faulkner County, Van Buren County and part of Conway County. Jones and Hawkins supported Bill Sanson of Enola in a three-man race. Sanson finished first in the Democratic primary, but didn't have enough votes to avoid a runoff against Russ.

"To help blunt the Hawkins influence, Russ had poll watchers come to Conway County on election day to monitor activity in the polling stations," Jimmy Bryant writes for the Encyclopedia of Arkansas History & Culture. "All of Russ' poll watchers were either lawyers or law school students." One of those poll watchers was Mark Stodola, the future Little Rock mayor.

Another was Joe Purvis, now a well-known Little Rock lawyer and longtime friend of Bill Clinton. The Log Cabin Democrat at Conway reported that Purvis "was told by two Conway County deputies at about 10 a.m. to leave the Menifee precinct or 'you won't spend the night with your wife.'" Sanson received 83 percent of the vote in Conway County, but Russ piled up large margins in Faulkner and Van Buren counties and finished with 402 more votes than Sanson.

Russ won the general election with 90 percent of the vote against a GOP opponent and never had another opponent for the Senate, which speaks volumes. He carried no grudges and, in fact, loved telling stories about members of the Old Guard he had known. Still, one of his favorite pieces of legislation to sponsor in his long political career was a 1977 act that strengthened the rights of poll watchers.

------------v------------

Freelance columnist Rex Nelson is the director of corporate community relations for Simmons First National Corp. He's also the author of the Southern Fried blog at rexnelsonsouthernfried.com.

Editorial on 01/18/2017