Robbie Robertson is having a moment.

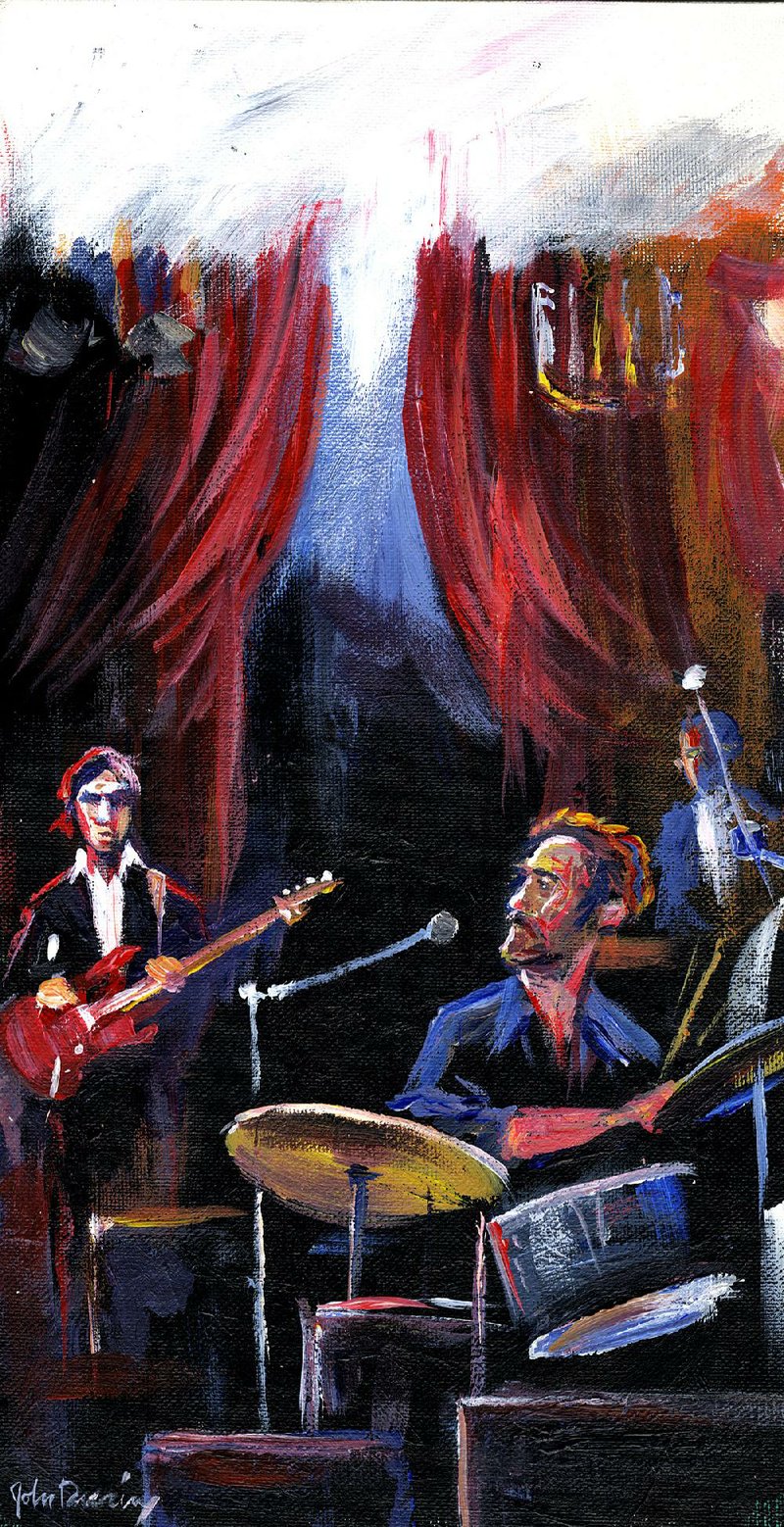

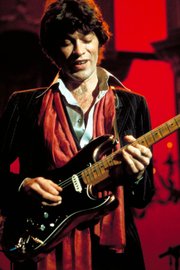

Best known as chief songwriter and guitarist for The Band -- a group that came as close to being "The Great American Band" as any group is ever going to come -- Robertson is on a book tour in support of his recently published biography Testimony (Crown Archetype, $30), which covers his life up until the Christlike age of 33. Not coincidentally, the book concludes shortly after The Band's farewell concert, The Last Waltz, a Thanksgiving Day show held at Bill Graham's Winterland Ballroom in San Francisco.

Nov. 25 marked the 40th anniversary of the concert, which was famously filmed by Martin Scorsese and featured such special guests as Bob Dylan, Paul Butterfield, Neil Young, Emmylou Harris, Ringo Starr, Ronnie Hawkins, Dr. John, Joni Mitchell, Van Morrison, Muddy Waters, Ronnie Wood, Neil Diamond, The Staple Singers and Eric Clapton. There's a special boxed set, available in several configurations, for which you can pay as much as $260. Screenings of the film are popping up all over, including at Ron Robinson Theater in Little Rock on Jan. 27. (Tickets are $5. For more information go to tinyurl.com/zlbh8gc.)

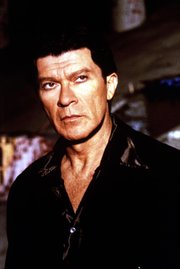

As this is Arkansas, you may have your own thoughts about Robertson and maybe about The Last Waltz. That's because there was another person who was in The Band, Levon Helm, who is pretty well beloved around these parts. Famously from Turkey Scratch, an unincorporated community in Phillips County, Helm was the lone American -- the lone Southerner -- in The Band.

That's important to remember, for the secret to The Band was that, because they were mainly Canadian, they were only sort-of Americans. (Though Canada is indisputably in North America, those of us in the United States tend to be pretty possessive of the adjective. To most of us, Canadians are only sort-of Americans, nice-enough folks but not as likely to clap on the two and the four as they are in Memphis or Muscle Shoals.)

Being 80 percent Canadian (and 80 percent rural-raised -- Robertson, who grew up in a Toronto neighborhood called Cabbagetown, was the only city boy) made them outsiders, which lent them perspective. That let them see straight into the heart of the wounded noble land to the south. For them, all of America was the South.

They first came together as the backup group for Huntsville-born Ronnie Hawkins (cousin to Dale), who took Helm (born in Marvell, 1940; no hospital in Turkey Scratch) with him to Toronto. Hawkins collected the best musicians from rival bands -- Robertson, Rick Danko, Richard Manuel and Garth Hudson -- for his backing group the Hawks.

After a few years, the Hawks split from Hawkins, becoming Levon and the Hawks. They got a big commercial break in 1965 when they became Bob Dylan's backing band, later collaborating with him on what became known as The Basement Tapes. Their 1968 debut album, Music From Big Pink, is often cited as one of the greatest rock albums of all time. Their second album, 1969's The Band, was even better.

Except for Robertson, who was a guitarist, they were all multi-instrumentalists. Helm was mainly the drummer, but he was playing guitar by the time he was 8 years old and added the mandolin soon afterward. Danko played bass, guitar, violin and trombone. Manuel played piano, harmonica, drums and sax. Hudson may have been the most accomplished -- he got an extra $10 per week as the band's "music instructor" -- and considered his rock 'n' roll organ playing a hobby, something to fill the time while he was preparing for a serious music career.

While they never went in for ostentatious instrument-switching onstage, in the studio it sometimes seemed that it didn't matter who was playing what. Their songs could sound like a chuck wagon full of marching band instruments falling down a mountainside in a tornado, but they were also full of subtle colors, of shifting timbres.

They famously had three lead singers: Helm owned a plaintive dirt farmer's drawl, sweat-soaked and seeded with grit; Danko a gliding, frictionless tenor; and Manuel -- whom Helm and Danko considered the lead singer -- moved between a keening falsetto and a dark, murderous baritone. With occasional support from Robertson (who only sang lead on a handful of songs) they formed rough-hewn harmonies, approximate and relative, but with the odd raw beauty of a Howard Finster painting.

They had The Last Waltz, and it was over, except for an anti-climatic final studio album, Islands, released in 1977 to fulfill a contractual obligation.

...

A lot of you have read and a lot more of you have heard about the longstanding feud between Helm and Robertson. It was mostly over money. In his 1993 book This Wheel's On Fire (co-written with Stephen Davis) Helm insinuated that Robertson took sole credit for writing songs that were group efforts and prematurely arranged the end of The Band to suit his career. And Helm was suspicious of Robertson as early as 1969.

"When The Band came out we were surprised by some of the songwriting credits," he wrote. "In those days we didn't realize that song publishing -- more than touring or selling records -- was the secret source of the real money in the music business. We're talking long term. We didn't know enough to ask or demand song credits or anything like that. Back then we'd get a copy of the album when it came out and that's when we'd learn who'd got the credit for which song ...

"When the album came out, I discovered I was credited with writing half of 'Jemima Surrender' and that was it. Richard was a co-writer on three songs. Rick and Garth went uncredited. Robbie Robertson was credited on all 12 songs.

"Someone had pencil-whipped us. It was an old tactic: divide and conquer.

"After that, the level of the group's collaboration declined and our creative process was severely disrupted. There was confusion. It's important to recognize Robertson's role as a catalyst and writer. But I blame Albert Grossman for letting him or giving him or making him take too much credit for the band's work ... I even confronted Robbie over this issue during this era ... I told Robbie that The Band was supposed to be partners ... Well, it never quite worked out that way."

Helm attacked Robertson as vainglorious, mocking him for showing up at their final concert in heavy makeup. He accused Robertson and Scorsese of editing the concert film to make it look like Robertson was the undisputed leader of the group. He even wrote that Robertson couldn't sing, that his microphone was routinely turned down during concerts, including the final one. ("The muscles on his neck stood out like cords when he sang so powerfully into his switched-off microphone," Helm wrote.)

Basically Helm blamed Robertson for breaking up a glorious collaboration.

Most Arkansans who were aware of the feud took Levon's side -- in part because he was one of us, and in part because he was a charismatic, soulful creature. Helm was a remarkable singer and multi-instrumentalist -- the "only drummer who can make you cry," critic Jon Carroll wrote -- who had an interesting second career as a character actor and whose last couple of decades of life were blighted by financial and health issues that might have been mitigated by a share of the royalty checks Robertson continued to receive for canonical Band songs like "The Weight," "Up On Cripple Creek" and "The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down."

When Helm was dying of cancer in 2012, Robertson says he went to the hospital to see him. He wrote on Facebook that he "sat with Levon for a good while and thought of the incredible and beautiful times we had together."

Others have disputed this story. They say that by the time Robertson arrived at the hospital, Helm had already slipped into a coma, that no final peace was made. People close to Helm have told me he didn't want Robertson there, that Helm would never have absolved Robertson.

...

That final scene doesn't appear in Testimony, although Robertson says he intends to continue the story in another volume that will cover his life after The Band, his collaboration with filmmakers like Scorsese and Jay Russell (another Arkansan, one who also worked with Helm on a number of projects) and his solo work. Instead, the book, which Robertson insists he wrote himself in longhand -- a departure from the typewriter-based lyric-writing method he picked up from Bob Dylan -- largely corroborates the story Helm told in This Wheel's On Fire, with a few key points of departure.

For instance, in Robertson's version he is the one who tells Dylan that he'd have to hire all the Hawks to get him and Helm in his backing group. ("'It's a kind of all-or-nothing situation,' I told Bob," Robertson writes.) But Helm insisted it was he who confronted Dylan's manager, Grossman, and told him, "Take us all, or don't take anybody."

It's not inconceivable that both were telling the truth, or at least that both believed they were telling the truth.

Aside from a few allusions to Helm's drugging and hot-headedness, there's little in Robertson's book that could be read as ungenerous. (There's a strange account of an aborted poker party robbery, and some have objected to an early scene in which he recounts Helm's father using racial epithets, but that feels more like honest reportage than a dig at his late partner. Helm's father seems more interested in shocking the callow Canadian kid than anything else.)

By 1976 Helm, Manuel and Danko all had fairly serious drug problems. Robertson writes that he felt their contributions to the group had suffered. He was fed up with life on the road.

And it seems likely that, at least in the technical sense, he did write the songs he's credited with writing. The way things work is that whoever writes the melody and the lyrics of a song is credited as the writer -- the rest (and often the greater part) of making a record is considered arranging. So while John Entwistle's dive-bombing bass run may be the most distinctive and salient characteristic of The Who's "My Generation," Pete Townshend is still considered the songwriter.

While "The Weight" might have been informed by Helm's stories and characters familiar to all The Bands' members, if it was Robertson who codified it into verses and choruses, if he wrote the lines and gave them to their voices to animate, then he wrote it. Legally.

But something else must be acknowledged. The Band wasn't really in the business of producing songs. They were in the business of making records, of producing four or five minutes of sonic art that, as it turned out, have endured for more than 50 years. As Helm pointed out, no one remembers the words of "Chest Fever" (not even Robertson, who has said he doesn't even "know if there are words to 'Chest Fever'"); what they know is Hudson's magnificent work on the Lowery organ.

It's interesting to note Robertson didn't write a memorable song before The Band began collaborating with Dylan, and that his subsequent solo career has not yielded many memorable songs. He has had some success -- "Broken Arrow" from his 1987 album Robbie Robertson might be his most noted tune -- but it's mainly as a soundscape artist, not as a singer-songwriter.

If the companion compilation CD released in conjunction with the book (also called Testimony) is supposed to make the case that Robertson's time in The Band was bookended by equally substantial work, it fails. It's heavy on Band and Dylan material, and only the inclusion of the tender Robertson-sung "Twilight (Song Sketch)" -- previously available only on the five-CD Band retrospective A Musical History -- raises it above the level of a profit-taking "Best Of" disc.

Considering that most of the great songs with which he's credited seem to draw from Helm's Southern experience, maybe it's reasonable to wonder how Robertson could have written them. But then Helm wasn't a prolific songwriter before or after The Band. While his late-career solo albums Dirt Farmer (2007) and Electric Dirt (2009) approached the best work of The Band, the first album consisted entirely of covers and Helm only co-wrote one track (the excellent "Growin' Trade") on the second.

In any case, Robertson grew rich off The Band's publishing royalties. He was free to pursue a career writing movie music or whatever he wanted. The rest of The Band had to work for a living. They had to tour, they had to record.

But the truth is, though they had some moments, The Band really wasn't The Band without Robertson either.

Email:

Style on 01/15/2017