Somebody shot the pelican.

We're standing along Arkansas 7 on the Arkansas-Louisiana line near Lockhart, La., early on a cloudy Tuesday morning in November. The sign that welcomes visitors to Louisiana features the state bird, and some good ol' boy has filled the pelican's belly with buckshot. We speculate that the crime was committed by a disgruntled Arkansas Razorback fan following a football loss to LSU. It's quiet here.

We pull into the driveway of a house on the state line and get out of the car. If people are in the home, they don't bother to come out and check on us. Chickens roam free in the yard, and a rooster crows out back.

This is pine timber country. Having grown up in the Gulf Coastal Plain area of southwest Arkansas, I've always thought that the southwest and south-central parts of the state should have joined up with north Louisiana and east Texas decades ago to form a state with Shreveport or Texarkana as the capital. There's not much difference--culturally, economically, socially -- in the three areas.

I was raised at Arkadelphia, just a few blocks from Highway 7. It's an iconic route than runs from this point south of El Dorado and east of Junction City all the way to the shores of Bull Shoals Lake near the Missouri border at Diamond City in Boone County. At one time or another, I've traversed every mile of this highway. But I've never done it all on consecutive days.

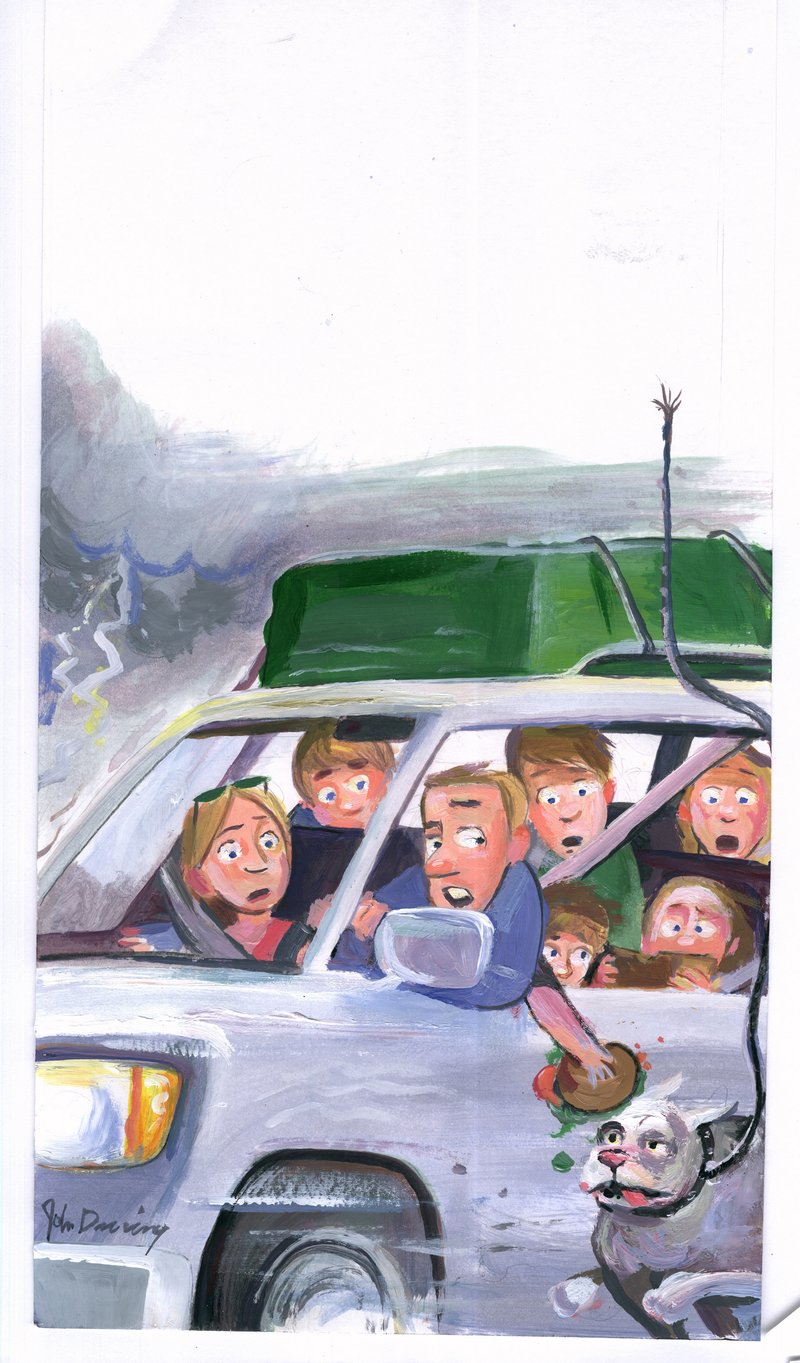

That's the goal for David Stricklin of the Butler Center for Arkansas Studies, Paul Austin of the Arkansas Humanities Council, and me. In two days, we'll drive through four of the state's six distinct geographical areas: the Gulf Coastal Plain, the Ouachita Mountains, the Arkansas River Valley and the Ozark Mountains; everything but the Delta and Crowley's Ridge. We'll see more deer

than we can count, several elk and a coyote along the way. We'll tell stories, eat well, see the autumn leaves changing colors, and meet interesting people. We'll come to appreciate both the beauty and the variety of Arkansas.

The excursion had begun the previous evening over dinner at the swank new Griffin Restaurant in downtown El Dorado's $100 million Murphy Arts District. Known as MAD, the arts and entertainment district is part of a broader effort to stem population loss in a county that has 15,000 fewer people than it had in the 1930s. With more than 1,000 square miles, Union County is the state's largest county geographically. About 90 percent of the county is forested, and almost a fourth of its residents live below the poverty line. Like most of Arkansas, cotton was once king in Union County. There are no longer row crops here. They grow pine trees, chickens and cattle instead.

The oil and gas industry remains important, though it's not nearly the driver of the south Arkansas economy that it was in the 1920s after Dr. Samuel Busey's well erupted on Jan. 10, 1921, near El Dorado. Historian Ben Johnson of Southern Arkansas University at Magnolia, with whom we had shared dinner at the Griffin, writes that there was "a thick column of oil that soiled clothes on wash lines a mile away. The rural market center was unprepared to become a boomtown. Hotels and rooming houses overflowed, and tent-covered cot spaces, restaurants and shops went up along South Washington Street. A newspaper reporter noted that a person walking along what became known as Hamburger Row could 'purchase almost anything from a pair of shoes to an auto, an interest in a drilling tract or have your fortune told.'"

Nearby Smackover also became a boomtown when oil was discovered there in July 1922. By 1925, there were 3,500 wells in the county pumping 69 million barrels of oil. Production declined considerably by the late 1930s. A few wells are still visible from Highway 7 as we make our way north to El Dorado and then turn onto the divided four-lane portion of the highway between El Dorado and Camden. It's easy to speed on this stretch, which passes near Norphlet and touches the outskirts of Smackover.

We go north from Union County into Ouachita County on our way to Camden on the Ouachita River. Camden has the feel of an old river town, albeit one that has seen better days. When I was a boy, Camden seemed like a city compared to Arkadelphia. After all, it had two high schools, Camden High School and Camden Fairview High School. It also had the smell of the giant paper mill that International Paper Co. had opened in 1928. The two school districts consolidated in 1991, and the paper mill closed for good a decade later. Camden has yet to recover. The city's population peaked in 1960 at almost 16,000. By the 2010 census, it was down to 12,183.

My father and I were frequent visitors to Camden in the 1960s and 1970s to watch the Arkadelphia Badgers play the Camden Panthers and the Camden Fairview Cardinals in football and basketball. On this day we pass the building that housed our favorite eating place in those days, the Duck Inn. It's now a Mexican restaurant. Just past the Duck Inn on Adams Avenue was a row of bars and juke joints that locals once called The Front. Most of them are long gone, replaced by vacant lots. Near what once was the depot, however, the White House Cafe still operates. It's the oldest restaurant in Arkansas, having been opened in 1907 by Greek immigrant Hristos Hodjopulas. It's far too early for lunch. We work our way through downtown Camden and cross the Ouachita River bridge.

There will be no more rural four-lane stretches of Highway 7 on this trip. The road here is narrow as we enter the heavily forested bottomlands along the river. The hardwoods form a canopy over the highway with railroad tracks to our right and the river to our left. This section of highway often floods, though that's not a problem in the dry autumn of 2017. Huge cypress trees have turned golden, and we comment on the number of cypress knees we can see as we peer through the woods, hoping to spot an alligator. It's beautiful in a Deep South sort of way.

In the community of Amy, we stop at Smith's Liquor Store, not because we need to buy beer, wine or spirits. We stop because it looks like the kind of place where one might meet a colorful character, and that's the case. Hartwell Smith Jr. has run this store for more than four decades. He has seen it all. With a dog to keep him company and no morning customers, he has plenty of time to tell stories, such as one about the beer joint down the road that Gov. Winthrop Rockefeller obtained a liquor license for in the late 1960s after the owner delivered him the black vote in Ouachita County. Back when Clark County was still dry, college students from Arkadelphia sometimes would make the drive to Amy to hang out in a small place they called the Tulip Country Club. Smith remembers those days fondly.

It seems as if there are more deer than people as we leave Amy and drive into Dallas County, passing through the community of Ouachita and then coming to Sparkman, a once-thriving lumber town whose population fell from 787 in 1960 to 427 in the 2010 census. Led by the likes of Quinnie Hamm, Irene Hamm, Cosie Fite and Majorie Leonard, a girls' basketball team known as the Sparkman Sparklers brought national attention to the community from 1927-30. Country music stars Jim Ed Brown and Bonnie Brown were born in Sparkman. We turn toward the west for a couple of miles before heading north again into Clark County at Dalark. We cross L'eau Frais Creek and Tupelo Creek east of Arkadelphia in an area where I once hunted quail with my father. The quail are all gone now. The small cotton and soybean fields that once marked this area have been replaced by pine plantations.

We emerge from the pine forest and experience our first and only large row-crop fields of the trip several miles east of Arkadelphia. This land in the Ouachita River bottoms was cleared decades ago for rice and soybean fields. For a short distance, it's like being in the Delta. We've pretty much followed the Ouachita River north from Camden, and we cross the river for a second time this morning. To our left, a new bridge is being built to handle the lumber trucks that will head to a giant $1.3 billion pulp mill that a Chinese company hopes to build in Clark County. We detour a couple of blocks off the highway so we can read historic markers on the grounds of the 1899 Clark County Courthouse, which was designed by noted Arkansas architect Charles Thompson. The courthouse was damaged in the March 1, 1997, tornado that destroyed all or parts of 60 city blocks in Arkadelphia. It was repaired over the objections of some county officials who wanted to build a new courthouse.

It's Battle of the Ravine week in Arkadelphia, so signs are covered at Henderson State University and Ouachita Baptist University to prevent vandalism by students in advance of the big football game. We get out of the car and walk the paved trail to what's known as DeSoto Bluff, though there's no evidence that Hernando DeSoto ever made it to what's now Arkadelphia. We simply called it The Bluff when I lived within walking distance of this place. The views are among the best in the southern half of the state. Looking toward the north, we can see where the Gulf Coastal Plain gives way to the Ouachita Mountains.

We're entering the Ouachita foothills as we cross the Caddo River and pass under Interstate 30 at Caddo Valley. We can see DeGray Lake with the Ouachita Mountains in the background as we go through the blasted-out rocks of what my father called Grindstone Ridge. This view was once the cover photo of the official state highway map.

The 30-mile trip from Caddo Valley to Hot Springs is a familiar one. Hot Springs was the "big city" when I was growing up, and we went there often to shop and eat out. The worst Highway 7 curves of my boyhood--including one that was known as Dead Man's Curve just north of Bismarck--have been removed through the years. Still, it's a curvy route as we make our way into the mountains. The cypress bottoms we had experienced just outside Camden earlier in the morning seem like a distant memory now.

An advantage to the year-round gambling now at Oaklawn Park in Hot Springs is that one no longer has to wait until the thoroughbred racing season--the period from January until April that marketers once promoted as the Fifth Season--to get Oaklawn's famous corned beef. We park at the track and walk through rows of what Oaklawn officials like to call "games of skill" so we can get our corned beef fix at a sports bar known as Silks. It's good to get out of the car for an hour.

Ahead of us on Highway 7 loom two mountain ranges that are separated by the Arkansas River Valley. We have many miles of Arkansas highway still ahead.

Next Sunday: North to Missouri

Editorial on 12/10/2017