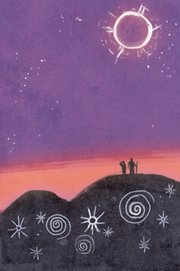

How did ancient Arkansans react to solar eclipses?

Imagine it: Anonymous One is padding along outdoors, just keeping his wits about him per usual, when all at once stuff starts going dark. Whoa!

Crickets pipe up. Turkey vultures descend to their roosts. Lightning bugs blink on.

If he's under leafy trees, maybe a bunch of tiny crescent suns appear on the ground at his feet. Something obliterates daytime for one minute ... another minute ...

And then it all clears up. Day comes back. Without so much as a heads-up whistle from a smartphone app.

Would he know not to stare at the sun? How would he "process" sudden onset night?

"We really don't know," George Sabo III says. As director of the Arkansas Archeological Survey, part of the University of Arkansas System, he thinks a lot about how little we know of the Indians who lived here before Europeans arrived.

"What I'm not going to tell you is that American Indians or other ancient people manifested wild native superstitions about things like the dragon swallowing the sun, causing them to rise up and do loopy dances on treetops and shoot arrows into the sky and so on and so forth in order to scare the dragons away and get their sun back," he says.

"They simply didn't do things like that."

Prehistoric people in Arkansas spent most of their lives out of doors, exposed to random hazards, and so they had to be keen observers. "In short, they were scientists just like folks in our society are scientists," he says. "If they did not have that capacity they would not have been able to endure for centuries and millennia."

And so he's inclined to believe that the prehistoric people who lived in Arkansas would not have lost their minds over occasional experiences like meteor showers or an eclipse. A total solar eclipse happens about twice a year somewhere on the globe, but any one place on the earth will fall within the shadow zone far less frequently -- and cloudy weather can easily obscure the special obscurity of the whole affair. But something like that would be remembered and talked about, including the information that the world did not come to an end.

"By the same token they probably did make up stories about it," Sabo says, "and they may have been fanciful stories that would amuse and delight children in the same way that we in our own society tell fables and amusing stories that amuse and delight children, and everyone else for that matter.

"But there was a science behind their knowledge which they translated then into their own cultural terms."

Although he knows of no rock art or other artistic artifacts in Arkansas clearly linked to a specific celestial event, archaeoastronomers have found such evidence elsewhere in North America. And evidence is not lacking that ancient Arkansans watched the skies. Embossed copper, engraved shell, woven fabric, decorated ceramics -- painted and engraved -- depict the sun, the moon, the stars. And "we do have in rock art illustrations of the sun, the moon and stars," he says.

"What that suggests is that they were acute observers of celestial phenomena and they recorded their observations. They understood it," he says. "Why they chose to record them in the ways that they did is something that we can't fathom with any kind of certainty."

NAKED EYES

Today's astronomers include specialists using computerized instruments far beyond the capacity of most of us to fabricate, let alone reinvent, and so it's easy to underestimate how much science rests on bare-eyed observation.

Across the globe down through time, smart people without telescopes have learned to predict the motions of celestial bodies. The first human in recorded history to predict a solar eclipse, which is an infrequent celestial routine, was Thales of Miletus in what is modern Turkey. He did so more than 500 years before the time of Christ -- and more than 2,000 years before the invention of the telescope in 1608.

Although prehistoric Indians didn't leave behind evidence in written language, we know, Sabo says, that they tracked solstices and equinoxes, which mark the changing of the seasons. Equinoxes -- when day equals night -- occur twice a year, at the onsets of fall and of spring, when the axis of the rotation of the earth (a line drawn between the north and south poles) parallels the direction the earth is traveling around the sun.

Solstices also happen twice a year, in winter and in summer, when the sun reaches its lowest and highest positions in the sky at noon.

Archaeologists are fascinated by ancient earthworks laid out as, or including, observation sites for solstices and equinoxes. The compound known as Toltec Mounds in central Arkansas is thought to have been such a place between A.D. 650 and 1050. About the same time in Illinois directly across the Mississippi River from St. Louis, Cahokia was a mound city with a great big woodhenge -- an observatory.

Another site, the Newark Earthworks in Ohio was occupied earlier, between the time of Christ and A.D. 400. It's a series of geometric moats and mounded walls aligned to moonrise and moonset positions that have been shown to track the moon's 18.6-year orbit cycle. The moon rises at the northernmost point in its orbit every 18.6 years.

Sabo says, "There are dozens of archaeological sites across eastern North America that are like Toltec or like the Newark Earthworks, and there are an even larger number out on the Plains and farther to the west that are evidence of Indians' interest in celestial events. ...

"So what this indicates is a very clever ability on the part of the Indians to transform observations about cycles in celestial movements, in cycles and phases, onto the geometry of the earth's surface in order to reshape the landscape so that it reflected the planar geometry.

"This is advanced science. It's something that's certainly beyond my capability and perhaps yours."

MOUNDS OF EVIDENCE

A national historic site, Toltec Mounds Archeological State Park at Scott is 100 mosquito-friendly, flat and grassy acres where three enormous man-made hillocks can be observed looking ... err, mound-like. The place is jointly managed by the Archeological Survey and Arkansas State Parks.

"We know that the site is built in such a way that there is a kind of observation point for equinox and solstice events," says station archaeologist Elizabeth Horton.

Research suggests it was built by a distinct culture known as the Plum Bayou People. They had many villages and small farms scattered around the Arkansas River floodplain and uplands. They built tall, flat-topped mounds beside rectangular plazas. With two plazas, today's park site was the largest and is thought to have been a ceremonial and governmental center.

In her article "Toltec Mounds," former station archaeologist Martha Ann Rolingson writes that although only three mounds are readily seen, over time the people erected 18 mounds in a compound surrounded by an 8- to 10-foot-tall earthen embankment, a ditch and an elbow of the Arkansas River that has become a marshy oxbow.

The Plum Bayou People left the site 500 years before the first Europeans arrived, and it is not known which, if any, modern Indians are their descendants. When Europeans arrived, the Quapaw lived in several villages along the river and knew the mounds, Rolingson writes, but they did not build them. The name of a powerful Mesoamerican culture, Toltec was applied in the 19th century in a mistaken belief that no local tribes were sophisticated enough to have made the mounds.

Two of the mounds are 49 and 39 feet tall, and the third is 12 feet tall. As Park Superintendent Stewart Carlton describes it, if you imagined riding in an elevator from ground level to the top of the largest mound, when the door opened you would step out onto the fifth floor.

These huge mounds would have been piled up and packed down one basket of dirt at a time.

"Some mounds were placed to line up with each other and with the positions of the sun on the horizon at sunrise and sunset on the solstices and equinoxes," Rolingson writes, suggesting that, at first, posts were hammered in to mark the sun's positions, and the mounds were later built on those marks.

"If you are here for the setting of the sun during the fall equinox, it's very interesting," Horton says. "It goes directly down behind Mound A. It's a very beautiful physical phenomenon to watch."

UNKNOWABLE

So is Toltec Mounds one of the 11 state parks that has planned special events today (see bit.ly/2uQgFKM)?

No, says Carlton, the park superintendent. Toltec Mounds isn't open on Mondays. Experiments have demonstrated there aren't enough visitors to justify the expense.

Also, he said, no evidence has been found at the mounds suggesting that the Plum Bayou People predicted eclipses or celebrated them in any way there.

RELATED ARTICLE

http://www.arkansas…">Most protected eyes even in ancient times

"That doesn't mean that they didn't," he says.

ActiveStyle on 08/21/2017