In April 2013, a middle-aged man named Scott Miller committed suicide.

He was a musician (not the Scott Miller who was in the V-Roys; that Miller is still very much alive and well, releasing records and maintaining a limited touring schedule while tending to his cattle ranch in Virginia). He had just turned 53. His death reportedly stunned his family and his friends.

Those of us who knew him only through his music and his writing might have suspected that he was introverted and morbid -- he'd written songs with titles like "Slit My Wrists" (What I need is not ways to go on/What I need is to slit my wrists and be gone) and "Together Now, Very Minor" (And write the obit when you do/He never ran out when the spirits were low/A nice guy as minor celebrities go/All right all together now now very minor I know) but you never know about people you don't know. I always imagined Morrissey was putting us on with his "woe betide me" shtick.

Anyway, Miller is important to me, even though I didn't get to know his band Game Theory until after they'd stopped recording and touring. My wife Karen was a fan. She contributed the band's entire catalog when we commingled our record collections in the early '90s.

I had heard of Game Theory; they were famously obscure -- Miller once said they had "reached national obscurity, as opposed to regional obscurity" -- and a lot of people who wrote about pop music in the '80s liked to use them as a point of reference. The legendary Mitch Easter, the jangle pop pioneer who worked with R.E.M. and led Let's Active, produced their albums from 1985 on. I knew that they were some kind of California nerd rock band, but I'd never heard them until Karen got me to listen to the 1987 double album Lolita Nation, 1988's Two Steps From the Middle Ages and the compilation -- you could call it a "greatest hits" record, but none were -- 1989's Tinker to Evers to Chance. Those were my gateway drugs. It took me years to get my hands on everything they'd released.

The band was active from 1982 through 1990, during which time they released five studio albums and two EPs, beginning with Blaze of Glory in 1982. (All of these went out of print in the '90s and remained unavailable until 2014, when the preservationist label Omnivore Recordings re-released them in deluxe editions.)

With Miller the only constant, Game Theory went through several incarnations, eventually involving 11 other members. (Before that, Miller had fronted a band called Alternative Learning, which he'd formed in high school.) In 1991 he formed The Loud Family, which released seven albums, none of which made much of an impression on the culture at large, probably because they were even pricklier than Game Theory.

I like the Loud Family. I love Game Theory. But you might not like either band.

Some find Miller's vocals annoying -- his natural register is pretty high and plaintive, to the point that he made a joke of it. On Two Steps From the Middle Ages he's credited on guitar and "miserable whine," which was how one critic referred to his voice.

But for a lot of us there's something genuinely thrilling about his songs, which are simultaneously complex and infectious, cerebral and playful, pretentious and self-deprecating. Miller deconstructed guitar-based pop, broke it down to its elements, then recombined it in original and surprising ways. He employed weird time signatures, tape collages and lots of chord changes, slouching toward a weird pop-prog fusion. He was a magpie who built an intricate architecture from rags and scraps. His esoteric lyrics betrayed the influence of T.S. Eliot, Thomas Pynchon and James Joyce.

It's amazing pop music -- angular and melodic with a hyper-literacy that is witty and dense and occasionally achieves a kind of elliptical poetry.

You look so cool with your young man's charm/but you're so distracted/The world leans on its boyfriend's arm, Miller sings in 1982's "Bad Year at UCLA," a post-breakup lament we can take as semi-autobiographical, though Miller was going to University of California, Davis, at the time. But "UCLA" had the benefit of scanning better, plus it located the drama to the famous campus in Westwood, a good deal more glamorous than the Sacramento valley satellite school.

I never noticed until after Miller's death that the song also contains another reference to self-extinction: And should you follow her car upstate/It's a long drive up/And a long way down off the Golden Gate.

. . .

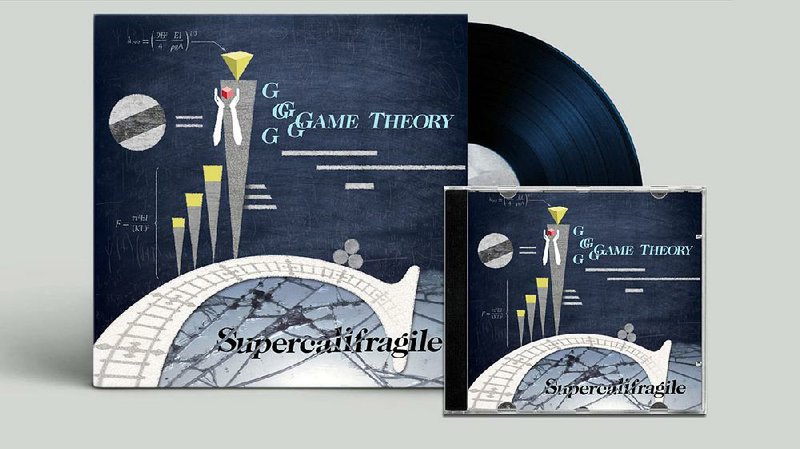

Before he died, Miller was working on a new Game Theory album, to be called Supercalifragile. His intention was to bring back former members of the band to work on the project.

After his death, Miller's wife, Kristine Chambers, enlisted the help of Ken Stringfellow -- a songwriter and producer who was a founding member of the Posies and the Minus Five and who has worked with R.E.M. and the reformed Big Star -- to finish the record. Miller left behind an archive of nearly finished songs along with snatches of lyrics and snippets of found sound. He'd recorded a number of vocal and guitar tracks and left extensive notes.

Stringfellow assembled a host of Miller's prior collaborators to finish the project, including Aimee Mann (who recorded a project with Miller in 2002 that is now considered lost), R.E.M.'s Peter Buck, and Ted Leo. Former Game Theory members Michael Quercio, Jozef Becker, Suzi Ziegler, Dave Gill, Nan Becker, Donnette Thayer and Gil Ray took part. They raised a production budget via Kickstarter. While the album was originally scheduled to be released about a year ago, it finally happened earlier this month.

It's pretty good, and entirely representative of what Game Theory was about. Instead of producing an all-star eulogy or a tantalizing glimpse at what might have been, Stringfellow and company have realized a record that stands with Miller's best work.

It's certainly the most accessible, if only because Miller's eccentric vocals -- featured on seven of Supercalifragile's 15 tracks -- are balanced by other voices, such as Mann's ("No Love"), the Posies' Jon Auer ("Between the Bottles") and Anton Barbeau ("I Still Dream of Getting Back to Paris").

It's not often that a posthumous release results in a satisfying listening experience. Too often it seems like profit-taking. Some of Miller's friends have said that in the months before his death he was pulling away from this project, that he was uncharacteristically shy about playing his new material for them. They wonder if he'd have lived if he'd actually gone through with the record.

Some artists have such strong visions that it's difficult to imagine anyone else completing their work. There are others who need collaborators. All I know about Miller is what I hear on the various records he's credited on, and my sense is that he was a songwriter who benefited significantly from the contributions of his bandmates. I think of him as Game Theory, but that's a convention of convenience. Those were always band records, and that's why they're all different.

Supercalifragile features the best band Miller ever had. It's a shame he had to die for it to come together.

Email:

blooddirtangels.com

Style on 08/20/2017