Look up the word "slacker" (slack•er) to find variations on a theme, depending on your dictionary:

• a person who avoids work or effort.

• a person who evades military service.

• layabout, idler, shirker, sluggard ...

Evading duty is pretty much what the word meant 100 years ago, but back then "slackers" weren't necessarily sluggish. Here's evidence from a report out of Oklahoma in the Aug. 6, 1917, Arkansas Gazette:

It is reported that 300 slackers are expected to arrive with the announced purpose of pillaging and burning the town.

Whoa! These were draft objectors, white and black tenant farmers -- overworked people -- who didn't believe the Selective Service Act of 1917 was constitutional. They had been riled up by crop failures and socialist activists opposed to the "rich man's war" declared that April by Congress.

Not only did these objectors refuse to report to their local draft boards, beginning Aug. 2, 1917, they mounted an armed insurrection. Bands of a few hundred farmers ambushed the Seminole County sheriff, damaged two bridges and cut phone lines.

"Central Part of Oklahoma Resists Draft" read the first headline about the resistance, in the Aug. 4 Arkansas Gazette. Fighting in Ada, Okla., had broken out after a meeting of 2,000 or more residents, and "1,000 heavily

armed possemen" from Seminole, Hughes, Pontotoc, Okmulgee and Pottawatomie counties planned to attack any insurgents they encountered at daybreak. Oklahoma's governor told them shoot to kill.

Here's part of a follow-up the Gazette published Aug. 6:

Two large posses tonight are continuing the search for armed bands which were organized to oppose the selective draft. However, Sunday passed almost without incident in the Central Oklahoma counties, which for three days have been the scene of attempted revolution against the government.

Captures of the resisters, members of the so-called "Working Class Union," the "Jones Family" and other organizations of kindred beliefs, have reached 193, according to the best count available at Sasawaka, in Seminole county, the base of operations. Of this number, 30 were taken today, the large part of them sending in word, generally by a woman, that they were ready to surrender. Small detachments would bring them in. But one death has resulted from the man hunt, that of Wallace M. Cargill, an alleged leader, late yesterday. ...

Dreams of conquest, riches and power have been implanted in the minds of the ignorant tenant class by organizers of the different organizations until they were led to believe that a show of force was all that was necessary to gain the promised fruits. Affidavits in the hands of officers tell of the innocent belief of tenants that to be drafted into the National Army was to go to sure death.

Those tenants weren't the only ones who felt dragged. Day after day in the first weeks of August, the Gazette and Arkansas Democrat reported on heavy appeals for exemption as draft boards in Arkansas called in their registered men.

The newspapers named names, of those who passed the physical exam, those who failed, those who sought exemptions, those who didn't show up. A Gazette report Aug. 9 noted some absentees had not received their notices because rural mail delivery was slow. But quotas were not being met, so in Little Rock and other cities, men who failed the exam the first time were re-examined by a different doctor. And each board was to impanel a prosecutor.

So it was a particularly ugly effort by the enemies of Little Rock Mayor Charles E. Taylor that sought to depict his secretary -- who was his son -- as a draft dodger. Young Charles Taylor was arrested Aug. 10 but quickly released when his birth announcement from the Gazette archive proved he wasn't old enough to register. Also that he had been a 10-pound baby.

LOST HORIZON

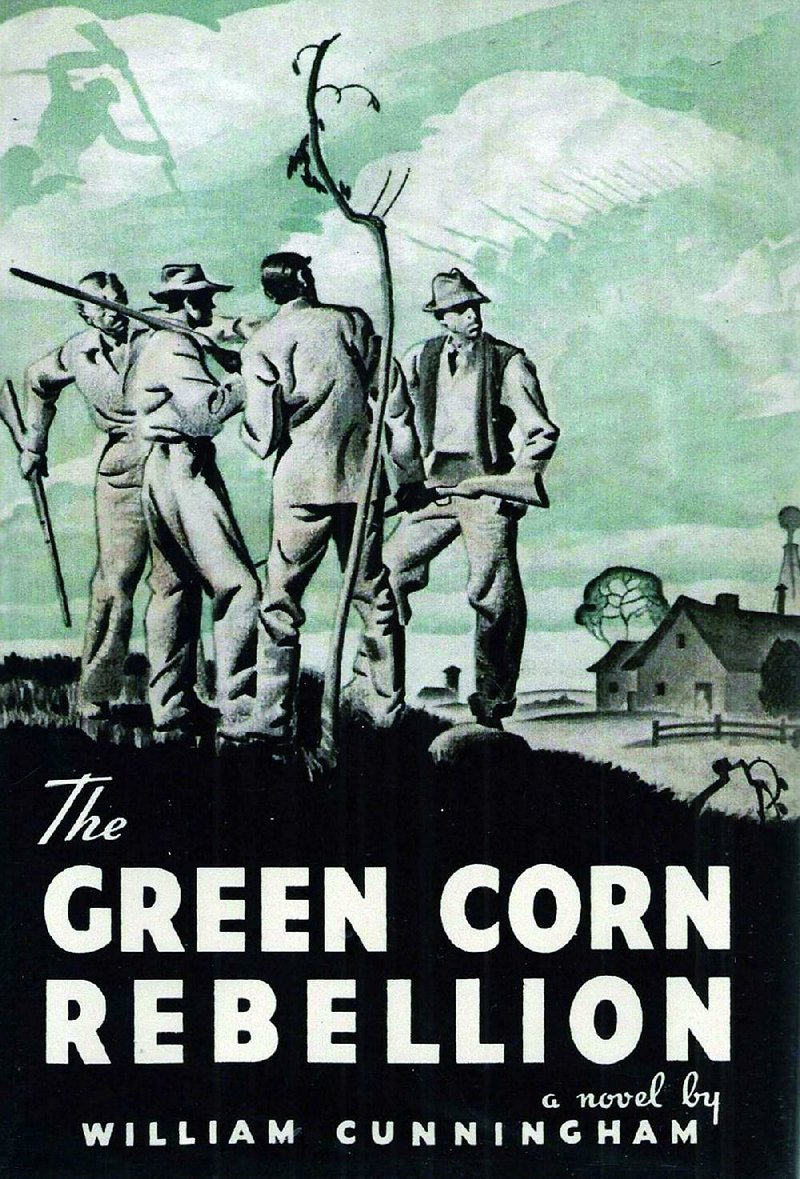

The Oklahoma anti-draft uprising today is known as the "Green Corn Rebellion." But the first use I find of that term in the Little Rock newspapers dates from a book review published in 1935: Gazette book editor Helen Hatley Horton praised William Cunningham's novel The Green Corn Rebellion, which uses the rebellion as a backdrop for romantic tragedy.

A peaceful farmer reluctantly goes to war to avoid exposing his affair with his sister-in-law, Happy McGee. Happy, otherwise a fine girl, fell into blissful adultery with him after an ill-judged indiscretion with a high school senior. "But," Horton writes, "'Happy's' life is meant for a sinister end, and finally she shoots herself."

Horton quoted another book lover, R.M. Berry of Mena: "Because of the realism in describing certain sooty situations, the novel may be banned by some overzealous censors."

All that to say this: The only mentions the Gazette made of "green corn" in August 1917 came in an ad for Arcade Grocery Co. and the cooking-advice column "Family Meals for a Week." The Democrat named it that August while contrasting "A Fashionable Dinner in Atlanta" with "A Fashionable Dinner in Paris" -- that included snails.

Humor aside, more than one nonfictional tragedy attended Oklahoma's draft resistance. Here's the Gazette from Aug. 7, 1917:

Moose Family Is Sorely Afflicted

Misfortunes have fallen thick and fast upon the family of the late Judge William L. Moose, who was attorney general of Arkansas at the time of his death about three years ago.

Yesterday it was learned that J. Fletcher Moose, who was shot and killed by a guard at Holdenville, Okla., late Sunday night, was a son of the late attorney general. Mr. Moose had been teaching school at Okemah, Okla., and had motored to Holdenville, ignorant of the fact that armed guards had been stationed on all the roads leading into the town, because of the anti-draft riots.

Mr. Moose encountered one of the guards, who ordered him to halt. Mr. Moose evidently did not understand, for he paid no attention to the order, and the guard fired. The bullet struck Mr. Moose in the head. He died soon afterward. He was 27 years old.

Compounding the tragedy, the Gazette went on, the wife of Capt. William Moose of the 8th U.S. Artillery had recently died at his post in the Philippines. Captain Moose had sailed for New York on July 18 to carry her body home.

His mother, the widow of the late attorney general, came to Little Rock yesterday en route to New York to meet her bereaved son. While here she received a message telling of the death of her son in Oklahoma and she returned at once to Morrilton.

She was accompanied to Little Rock by her son, Clifton Moose, who is afflicted with appendicitis, and who, on the advice of physicians, had come to Little Rock to undergo an operation. He returned to Morrilton with his mother.

From the 1920 U.S. Census records and from postings on FindaGrave.com by descendants of William L. and Lenni Porterfield Bright Moose (see bit.ly/2u5nj3g), we know that Clifton survived. He lived until 1932, when he joined his parents and several siblings in Morrilton's Elmwood Cemetery.

Next week: He Testifies to German Brutality

ActiveStyle on 08/07/2017