Northwest Arkansas researchers, churches and residents are sharing knowledge and using science to improve the health of Hispanic and Marshall Islander communities and of the region in general, participants say.

The 3-year-old Office of Community Health and Research at the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences works with those groups to find and refine ways to treat or prevent high blood pressure, diabetes and related health concerns. Those issues touch all demographic groups but are several times more common among some immigrant groups and their descendants.

Web watch

For more information about the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences Office of Community Health and Research, including in Spanish and Marshallese, go to http://northwestcam…">northwestcampus.uam…

"We see a lot of stuff changing," said Julio Gonzalez, youth pastor and worship leader for Iglesia de Cristo Miel in Rogers, pointing to a community garden, soccer league and nutrition classes that have appeared at the church in recent years with support from the university and local nonprofit groups. "It's a good partnership. It's a big blessing for us."

The theme since the beginning has been collaboration, said Pearl McElfish, the office's director and associate vice chancellor for the university's northwest campus in Fayetteville. Researchers, many of them bilingual, sat down with religious and civic groups to choose the health priorities, design the studies and share the findings in understandable and culturally informed ways.

Research so far has been mostly exploratory, pinning down the communities' knowledge about and barriers to managing diabetes, for example, or simply getting a clearer picture of how big a problem the disease is. But even those first steps had never been done, particularly with the Marshallese, McElfish said.

"We're definitely forging new ground," she said in January. "It's just a population that has not been looked at in the South and Midwest."

Ground work

The Marshallese number about 12,000 in Northwest Arkansas, among the largest gatherings outside the Marshall Islands, according to researchers' analysis of school enrollment and other data.

Dozens of U.S. nuclear weapon tests on the islands devastated native fish and other food, turning locals' diets toward processed, fat- and salt-heavy foods while intensifying the risk of cancer from lingering radiation. In return for continued American access to the territory, Marshallese can travel and work in the U.S. without visas.

The population of Spanish speakers and their descendants has soared to more than 80,000 in the metropolitan area, according to census estimates. Many are immigrants who came to work in food processing and construction, though those industries dominate less with each generation.

These histories and other factors contribute to median incomes for Marshallese and Hispanics thousands or tens of thousands of dollars lower than the rest of the area's residents. That in turn leads to a lack of transportation and health care, leaving pockets of need in a prosperous region, McElfish said.

University surveys find roughly half of the region's Marshallese have diabetes, compared to 9 percent of all U.S. adults with diabetes, and most are overweight. Hispanic people also suffer disproportionately from diabetes and high blood pressure, according to the federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

To fight these problems, the community health office is switching gears to direct interventions that are gradually fine-tuned and expanded. It's too early to see broad results, but participants point to more and more signs of success: community gardens and health fairs at dozens of churches, fresh fruit at parties and gatherings, pastors who talk with their congregations about taking care of their bodies.

"I've seen older folks who, boy, they're so strict in their diet now," said Patrick Boaz, who runs a Marshallese language newspaper called Chikin Melele -- a pun on many islanders' jobs at poultry companies that translates to a place of information or understanding. "Even their countenance changes. They feel better, they're happy."

The social angle is key in cultures that heavily emphasize the family and group, participants have told researchers.

One study published in 2015 found weekly sessions of Marshallese family diabetes education could lower family members' blood sugar levels by several percent after six weeks and did a better job keeping participants on board than past attempts that didn't include family. A larger version of the study is going on now.

"When we do something, we do it in groups. You never see a Pacific Islander go somewhere by himself," Nia Aitaoto said at a health training for a dozen Marshallese pastors and their wives in January. Aitaoto, who is Samoan, co-directs the health office's Pacific Islander center with McElfish.

Knowledge has gone from community to university and vice versa, Gonzalez said. He knew next to nothing about gardening but now helps grow lettuce and other vegetables that go into the church's meals and food pantry, he said. On the other hand, his church taught researchers about the cultures and cuisines of Mexico, Panama, Honduras and other homelands and how to adapt nutrition classes to them all.

"We were just pleased that they'll let us come along," said Lisa Smith, administration director for the community health office.

The impact of such work helps the broader community, McElfish said, such as by giving health researchers experience with adapting to different cultures or personal situations and overlapping with other university projects.

The university is working with Springdale Public Schools and several food pantries for the next several years to make their food less salty, and a 2015 study from the community health office recruited participants of all ethnicities for the long-term National Children's Study by involving prenatal care clinics.

Joining paths

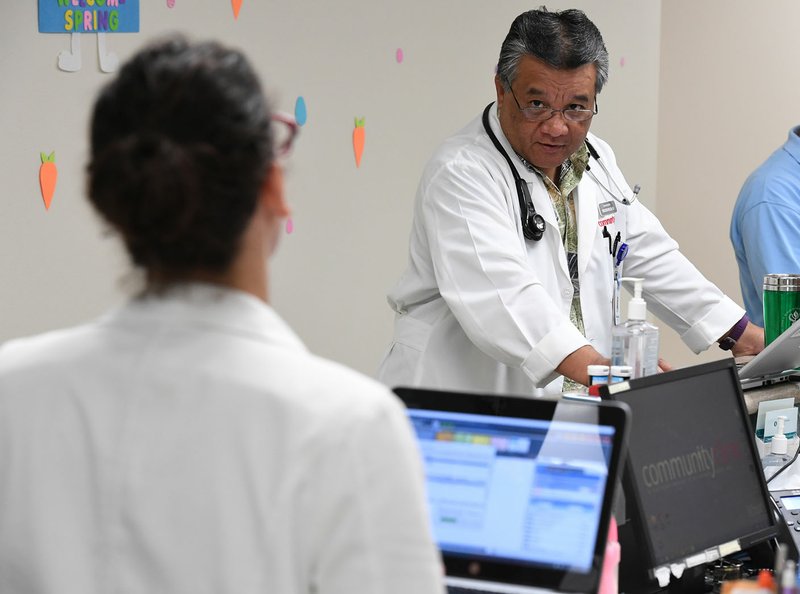

Dr. Sheldon Riklon had bad news for a Hispanic patient one recent Friday afternoon: the man needed to cut down on tortillas and rice to help control his blood sugar before an approaching surgery.

"All the things you like to eat," Riklon said with a laugh, the patient's daughter translating. "You do your part, I do my part, and we work together to make it happen."

Riklon, a Marshallese physician, joined the medical university as an associate professor last year and also treats patients on the family medicine side of the low-cost Community Clinic in Springdale. Conversation in English, Spanish and the rapid-fire, rounded syllables of Marshallese fill the clinic's main room.

"You can tell they appreciate the freedom to talk in Marshallese and express what they've always wanted to express," Riklon said of his Marshallese patients, who come to him with issues such as diabetes, cholesterol concerns and common coughs.

Allan Elanzo, a Marshallese man who moved to Springdale from Hawaii last year, doesn't have health insurance but started coming to the clinic about a month ago specifically because he heard about Riklon. Talking to Riklon is easy, he said through a translator, and he plans to return.

Riklon is representative of a long-term goal of the university and local health care providers in general: increasing the number of bilingual researchers and care providers in a virtuous cycle and connecting with minority communities. He and other Marshallese researchers at the university also work to translate or create materials for the health office's studies and interventions, among other duties.

The university in June plans to hold a conference for Pacific Islander high school students and parents aimed at encouraging them to go into the health care field.

"That's one of my goals and one of my dreams," Riklon said. "I know it's going to happen."

NW News on 04/23/2017