Frans Van Liere opened with an Anglo-Saxon riddle from the 10th century:

"Who am I? First I am killed by an enemy, soaked in water and dried in the sun, where I lost all my hair. After that, I am stretched out and scraped with a knife blade, and smoothed. Then I am folded. A bird's feather travels over my surface, back and forth, leaving black marks. Finally, I am bound and covered with skin, gilded and beautifully decorated.

Sponsors

Symposium: Bible Craft: Making and Remaking Scripture in Early Britain and America

When: April 6-7

Where: University of Arkansas

Funding: Mellon Foundation scholars of bibliography fellowship awarded in 2015 to Joshua Byron Smith, UA assistant professor of English

Sponsors: Andrew W. Mellon Foundation; Rare Book School, University of Virginia; Medieval and Renaissance studies department, indigenous studies department, English department, Fulbright College of Arts and Sciences and the Honors College, University of Arkansas.

"If the sons of men would make use of me, they would be safer and more sure of victory; their hearts would be bolder, their minds more at ease, their thoughts wiser. They would have more friends, companions and kinsmen (true and honorable, brave and kind), who would gladly increase their honor and prosperity, holding them fast in love's embraces. Ask what I am called, useful as I am to men. My name is famous, bringing grace to men, and itself holy."

Van Liere, a professor of medieval history at Calvin College in Grand Rapids, Mich., spoke April 6 as the keynote in the symposium, "Bible Craft: Making and Remaking Scripture in Early Britain and America," at the University of Arkansas.

"What is it," Van Liere asked his audience.

"It's a book. It's a Bible," he answered. "But is it?"

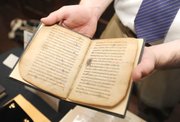

Van Liere held up a Bible, "stolen" from his hotel room, he said.

"It's a handy-size book. It contains the entire canons of the Old and New Testaments.

"But it's probably a far cry from what the author of the riddle had in mind."

Van Liere noted that the riddle made no mention of the act of reading, rather, it focused on the process of making the book, its outward appearance and decoration, and the social implications of its use.

The riddle didn't describe a Bible in the modern sense, Van Liere continued. More likely, the riddle described a Gospel book, a liturgical object that was carried up the aisle of a church during a solemn procession, raised high so everybody could see its decoration. During the service, the item would be wafted with incense and kissed by the priest.

"In many ways, the respect and reverence shown to this book is very much like that shown to the relics or the elements of the Eucharist, which also are elevated during the celebration of Mass," Van Liere said. "It is a sacred object, but also a text that creates community and bonds of kinship and one that ensures the user of his hope for personal salvation."

Van Liere shared slides of some of the decorated gospel books: an ivory carving of Christ crucified, with gold and precious stones.

"Keep in mind, the modern concepts of 'books' and 'literacy' can be quite different from what they were in medieval society," Van Liere continued. "Did medieval people possess Bibles? Could they even read? We would assume not, but we don't know. And it would be absurd to expect the piety of early medieval people to conform to post-Reformation expectations.

"Instead, I would like to cite here some examples of recent scholarship that have taught us to ask new questions, and make us reconsider how medieval people saw -- and used -- their Bibles."

OATH MAKER

"First I want to consider the use of the Bible in a ritual that seems to emphasize the Bible primarily as object: in taking an oath," Van Liere began. "It would seem, that in this ritual, the Bible is in the first place appreciated for its object quality. You can take an oath on the Bible and respect its symbolic quality, without having any idea about its contents."

He cheekily showed slides of both Donald Trump's and Barack Obama's inaugurations as president.

Oaths were important in the Middle Ages as part of the judicial process. An oath could establish the truth of a witness account, rather than going through the trouble of proving it. And it would establish feudal relationships.

"Unfortunately, we know a great deal more on the text of medieval oaths than about the actual ritual surrounding it," Van Liere said. "Taking an oath could be done while holding or touching one's beard, other body parts -- including the testicles (which is where this body part gets its name, from testare, 'to swear') -- or sacred objects -- such as a church altar, relics or a gospel book. "

Taking an oath on a complete Bible seems completely absent in the Middle Ages. Medieval oaths were taken, not on a Bible, but on a gospel book, he said.

"I would suggest there is a theological reason for using the gospel -- not just a ceremonial one," Van Liere said. "More than any other part of the Bible, the gospels were seen as the verbum dei, 'the word of God, incarnate in Jesus Christ, the word made flesh.' Swearing on the gospel was very much the same as swearing on the incarnate body Christ, who himself was the 'truth.'"

Oaths were taken with one hand on the book or holding the book. Kissing the book became customary -- at least in England -- after taking the oath. And not kissing the book could have invalidated the oath, Van Liere continued.

Eyal Poleg, a materials historian and senior lecture at Queen Mary University of London, observes in his book, Approaching the Medieval Bible, that sacred books were used in oath taking "to endow civic and religious spectacles with an aura of sacrality. The talismanic use of the book was key to ecclesiastical hierarchy and civic governance," Van Liere quoted.

"The gospel books were preferred (for oaths) exactly because this object was a text," Van Liere continued. "They were preferred because they were books. They emphasized the value of the written word as a guarantee for the validity of the bonds of power that tied society together. No other book would do."

GIFT GIVING

"The second thing you can do with a Bible is give it as a gift," Van Liere said. "I think this is an interesting example where we can see the object-quality and the text-quality of the Bible overlapping. Gift giving is one way to strengthen bonds between the members of a community. Giving a book was symbolic of the commitment to a shared idea contained in the text of that book, which transcended the common bonds of friendship."

Van Liere shared the story of a Bible gift. He wrote for his presentation:

The double monastery of Wearmouth-Jarrow was founded in the late seventh century, under the protection of the Anglo-Saxon king of Northumbria, Egfrid. It was an important part of the Roman mission to the Anglo-Saxon church, first initiated by Pope Gregory the Great in 596. Its first abbot, Benedict Biscop (d. 690), cultivated close ties to Rome. In the course of his life, he visited Rome numerous times, each time bringing back with him stacks of books of "on all subjects of divine learning," sacred images and relics.

After the death of Benedict, Ceolfrid became abbot of both monasteries. The double monastery housed not only a library but a scriptorium, where monks labored in copying bibles. Ceolfrid had brought back a large one-volume copy of a bible from one of his Roman journeys. Under his direction, they copied three new bibles, modeled after this bible. Two of the copies were for the use of the two monasteries, but the third he carried with him as gift to Pope Gregory II, when towards the end of his life he set out to revisit the holy city. Sadly, Ceolfrid never made it all the way to Rome; he died on the way in Langres in France, "among people who did not speak his tongue." The bible he carried with him was brought to Rome, however, and remained there, until at some time in the eighth century, it became a gift again. The name of the original giver, "Ceolfrid abbot of the Angles," on the first folio was erased and replaced by "Peter, bishop of the Lombards", and the book was presented to the newly founded abbey of San Salvatore on Monte Amiata in Tuscany, where it stayed, until the 18th century. Today, it is housed in the Biblioteca Laurenziana in Florence, and already in the Renaissance, it became recognized as the oldest and most complete copy of Jerome's Vulgate translation we possess.

"But why would Ceolfrid bring a copy of the Bible back to Rome -- especially if it was modeled after a Bible brought from Rome, only decades before? Did they not have bibles in Rome," Van Liere asked. "Of course they did. Ceolfrid's gift was symbolic. It represented the ties that bound the two communities together: an adherence to the eternal and unchangeable text of divine law."

Another Bible was commission by Bishop Gerfrid of Laon in 798, to be presented to the rebuilt church at the Abbey of St. Riquier, Van Liere continued. The Bible contained a dedication poem by Alcuin -- a scholar in the Carolingian court -- in which he praised Gerfrid for rebuilding this house of God:

Here this saintly codex contains in one volume all the mysteries of the old and new law. Here is the fount of life, here are the precepts of salvation. Saints wrote it through the ages, God dictating the words. This is the holy faith, the entryway into heaven.

"There is some discussion as to the actual function of these Bibles, whether these Bibles were intended for use in the church," Van Liere posited. "Others have argued that 'church' is not the actual architectural setting, but means a more general body of believers.

"I would argue there is no essential difference between the two. The Carolingian state was a society bound together by a shared textual heritage. Even though the individual members of that society might have limited access to this text, it nevertheless represents the permanence of the ideals they shared -- because these ideals resided in the written word of God, not the fallible memory of humans. The presence of the book in the church is symbolic of the relation the text has to the community on earth."

MORE STUDY

"At the end of this exploration of the Bible as book and the Bible as text in the Middle Ages, I am afraid I have left you with a somewhat broad canvas," Van Liere told his audience. "I am not sure I have a unifying thesis -- exactly what I fault my students for.

"When studying the Bible in the Middle Ages, we sometimes need to look beyond the obvious answers," he continued. "Things are not always what they seem. But we'll only discover that when we pay attention to the small differences."

In studying the medieval Bible, historians will have to pay attention to changes in the meaning and use of the Bible over the long term, Van Liere said. They will have to explore the use of the Bible in the context of the specific community.

"The world of the medieval Bible can be at times familiar and recognizable, but we'll also find plenty of things that strike us as strange and alien," he said.

"Was the Bible regarded as a treasure chest or a story book?" Van Liere asked. "The answer lies in the question of who was reading the text and for what reason. Its use most often determined the shape of the object itself."

NAN Religion on 04/22/2017