Midazolam, the first drug in Arkansas' three-drug lethal injection protocol, cannot be used by itself as an anesthetic, an Oklahoma pharmacologist testified Tuesday.

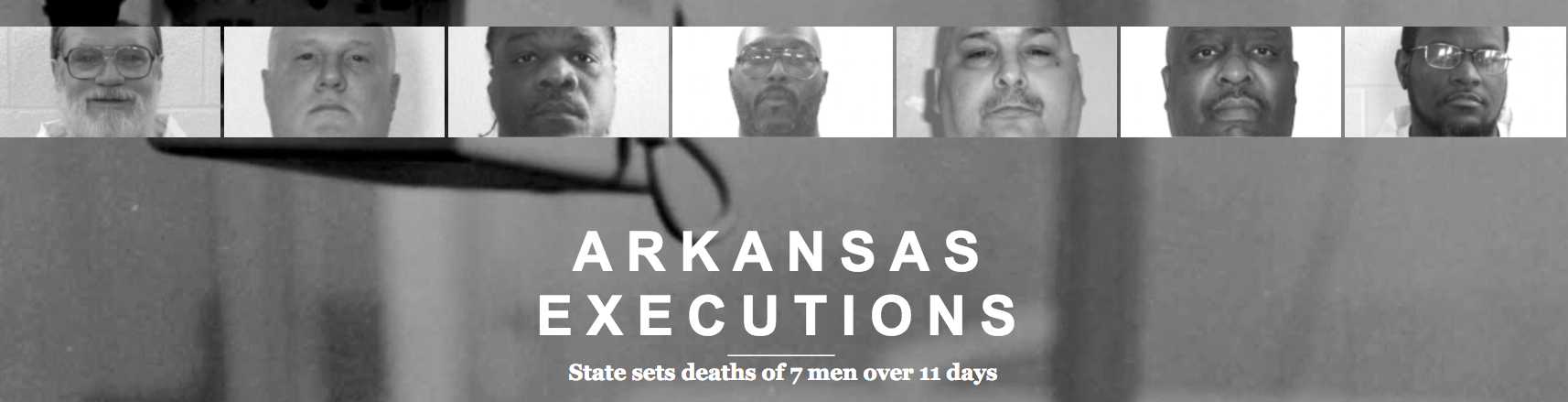

EXECUTIONS: In-depth look at 4 men put to death in April + 3 others whose executions were stayed

Click here for larger versions

Craig Stevens' testimony kicked off the second day of a hearing in which attorneys for seven condemned inmates want U.S. District Judge Kristine Baker to stop the state from carrying out the executions under a compressed time frame this month. They argue that the tight schedule undermines the prisoners' rights to be adequately represented and receive due process.

The executions of seven death row inmates over 11 days, beginning at 7 p.m. Monday, were scheduled because the state's limited supply of midazolam expires at the end of the month. Gov. Asa Hutchinson agreed to the schedule after the Arkansas Supreme Court dissolved a state-level stay.

Stevens, who holds a doctorate and teaches at Oklahoma State University, testified that midazolam is a benzodiazepine, a class of drugs not designed to be used by themselves for anesthetic purposes. He said he has analyzed in-vitro studies, or studies done in petri dishes, to discover at what doses the drug starts to affect cells and at what point it stops producing an anesthetic effect, or reaches its ceiling of effectiveness. The "ceiling effect," Stevens said, occurs after the injection of 220 milligrams of the drug -- or about half the dosage that Arkansas' protocol calls for a condemned prisoner to receive.

[FULL TEXT: Read the American Bar Association's letter to Gov. Asa Hutchinson on executions]

Arkansas' lethal injection protocol calls for the injection of 500 milligrams of midazolam, which Stevens and others have testified doesn't block pain, as has been claimed, but is instead used as a calming agent and to create amnesia. The second drug administered intravenously is vecuronium bromide, which is often used to paralyze muscle movement while patients undergo surgery. It is followed by potassium chloride, which stops the heart.

Attorneys for the inmates say the use of midazolam doesn't protect the patient from feeling immense pain after the injection of the other two drugs, particularly potassium chloride, which creates a strong burning sensation as it destroys the vein through which it is injected. They have previously argued that the three-drug protocol thus violates the prisoners' rights to be free from cruel and unusual punishment under the Eight Amendment, though the case being heard this week focuses on the execution timetable.

Attorneys for the state questioned the reliability of Stevens' assertion about the "ceiling effect" of the drug. Stevens called it "an attempt that I think is scientifically valid," while also acknowledging that the research needs to be "more robust" to be published in a scientific journal.

Despite the uncertainty of some scientific theories, Baker told attorneys that because she is presiding over a preliminary hearing, and because of the urgent nature of the case, she is giving more leeway to scientific testimony than she would in a trial.

Asked if he believes the use of midazolam, also known as Versed, can render an inmate "insensate" to the other two drugs, Stevens replied, "I don't believe it can."

While lower doses of midazolam in other states have led to concerns that the condemned prisoners experienced pain, Arkansas' higher dosage doesn't guarantee that the pain problem is solved, Stevens said.

"You can't give more and more of a drug and expect it to change its nature," he said. "Benzodiazapines can't produce the same effect as barbiturates, because they work differently."

Assistant Attorney General Jennifer Merritt told Stevens that under the law, Arkansas can use either a barbiturate or the three-drug protocol that has been upheld by the U.S. Supreme Court.

"As a matter of law, the Arkansas Department of Correction has only these two options, and can pick one based on the availability of the drug," she said, adding that the department is using the three-drug cocktail only because it has been unable to find a manufacturer who will sell a barbiturate to the state for execution purposes.

Meanwhile Tuesday, a third federal lawsuit and injunction request was filed on behalf of condemned inmate Marcel Wayne Williams, whose attorneys say his unique medical conditions -- primarily, being obese and diabetic -- create a strong likelihood that the protocol will affect him differently from the way it would an average healthy inmate. They said that an anesthesiologist who has examined him believes that if the protocol is administered to him, it creates a "substantial risk" that he will experience a prolonged, painful execution, or that he won't die and will be rendered permanently disabled from oxygen deprivation and multisystem organ failure.

The lawsuit asks U.S. District Judge James Moody Jr. to declare that the protocol thus violates Williams' Eight Amendment right to be free of cruel and unusual punishment, and to permanently prevent the state from using it on him. The suit recommends using a high dose of a fast-acting barbiturate instead.

Stevens testified that there are alternative drugs, such as sevoflurane, which is an inhalational general anesthetic, or a gas, that is "like barbiturates on steroids" because if affects the brain more strongly than a barbiturate would and is capable of causing death by itself. He also discussed the possibility of using a massive dose of opioids, which would basically stop a person from breathing, noting that opioids are known to produce a euphoric effect and an anesthetic effect, creating a rapid, painless death.

In response to a question from Merritt, Stevens said he wasn't aware that Arkansas has "no requirement" to use a pharmacological equivalent.

Stevens agreed that a "black box warning" on packages of midazolam says it should only be used in a hospital setting because it has been known to cause respiratory distress and it could cause a patient to stop breathing or die. The typical dosage used for sedation, according to the package insert, is 1 milligram to 2.5 milligrams.

While he agreed that higher doses of injected midazolam bring on quicker sedation, Stevens emphasized the word "sedation." He noted that according to the manufacturer, the drug can be used for the "induction of general anesthesia," before the administration of other anesthetic agents.

Merritt told Stevens that the state "reached out" to the manufacturer of a barbiturate, Nembutal, also called pentobarbital, but the company refused to sell the drug to the state for execution purposes. She also noted that in the past, the department tried to obtain Nembutal from an overseas supplier, only to have it confiscated by agents from the Drug Enforcement Administration.

"There are other ways" to get the drug, Stevens said, such as at a compounding pharmacy, but he acknowledged that he was unaware of any such pharmacy willing to supply the drug for execution purposes.

Also Tuesday, Baker heard from an assistant federal public defender in Alabama who said he watched client Ronald Byrd Smith Jr. die after a lethal injection of 500 milligrams of midazolam in December, coughing and clenching and unclenching his fists throughout the 17-minute procedure.

An Oklahoma journalist, Ziva Branstetter, testified about watching an agonizing 43-minute lethal injection of Clayton Lockett on April 29, 2014, in McAlester, Okla. Authorities later determined that Lockett had received a 100-milligram injection of midazolam, but because of an improperly placed intravenous line, much of the drug went into his flesh, leaving him conscious for several minutes after the injection began. Branstetter described seeing him kick his right leg, roll his head from side to side and mumble before "writhing and bucking."

Also Tuesday, American Bar Association President Linda Klein sent a letter to Hutchinson, saying, "Because neither Arkansas decision-makers nor defense counsel currently have adequate time to ensure that these executions are carried out with due process of law, we simply ask that you modify the current execution schedule to allow for adequate time between executions."

The letter said the group hasn't taken a position on the death penalty as a legal punishment. In Arkansas, state Bar Association President Denise Hoggard said her group has remained silent on both the death penalty and the governor's execution schedule.

Information for this report was provided by John Moritz of the Arkansas Democrat-Gazette.

Metro on 04/12/2017