MEMPHIS -- Five miles due north of Graceland, the Stax Museum of American Soul Music sits in a neighborhood that Yelp! commentators call "sketchy" and locals call "Soulsville."

Maybe it does feel sketchy to Canadian tourists, but driving through Soulsville on a late summer afternoon, it feels more like a sleepy Southern town than any sort of urban ghetto. It is sun-dappled with the kind of screen-doored little groceries that might put the sentimental in mind of their grandparents' town. It feels more antique than gritty until you reach a suddenly gentrified block of McLemore Avenue. There's the Stax Music Academy and The Soulsville Charter School. And, yes, a police station.

And a movie theater marquee announcing the Stax Museum.

"Soulsville" is a rejoinder to the sign hung on a former photographer's studio in Detroit. Berry Gordy dubbed Motown's first headquarters "Hitsville U.S.A." So Stax Records proclaimed its 'hood "Soulsville." And if you think you perceive something of a snarl in that answer you're getting close to the heart of the rivalry. Motown was all smooth glamour and gospel-inflected pop confectionery while Stax was earthier, tighter, tougher and closer to the bone.

Motown had more hits. It had the Jackson 5, The Four Tops, Diana Ross and the Supremes, Smokey Robinson, Stevie Wonder, Marvin Gaye. The artists made television appearances and toured internationally. As a side effect, Gordy turned lots of white kids on to black pop.

On the other hand, Stax had Rufus Thomas and his daughter Carla. It had Booker T. & the MGs. Gus Cannon. The Bar-Kays. Freda Payne. Otis Redding. Little Milton. Albert King. Isaac Hayes. Maybe they didn't have quite the cross-cultural appeal -- maybe you didn't see them as often on TV. After all, if you wanted to see Shaft, you had to ask your momma.

Not that you have to take sides.

You can love the Jackson 5's "ABC" and Booker T. & the M.G.s "Green Onions." But the Stax Museum of American Soul Music has invited us to compare and contrast the styles by hosting an exhibit, which will be up through Nov. 8, called "Motown Black & White," which includes clothing, jewelry and never-before-seen photos of Motown artists from the personal collection of Al Abrams, who, as the first Motown employee hired by Gordy, became the label's founding publicist and public relations director. (After he left the label in 1967, Stax became one of his clients.)

Abrams, who died in 2015, was a "white Jewish kid in an all-black company" who relied on chutzpah to market his clients to a wider audience than they might otherwise have enjoyed. He was especially proud of having landed the Supremes the cover of a nationally distributed newspaper insert section called TV magazine. (It proved, he told the Detroit Free Press in 2011, that "we can put black people on a cover that will sit in peoples' living rooms for a week, and they won't cancel their subscriptions.") And with Bob Dylan intimate Al Aronowitz, Abrams cooked up the story that Bob Dylan had called Smokey Robinson "America's greatest living poet," a bit of mutually beneficial myth-mongering.

Abrams was a pack rat who turned his collection of photos, news releases and other label effluvia into the coffee-table book Hype & Soul -- the basis for the current exhibit -- in 2011.

While the Motown exhibit is what drew us to Soulsville, it pales beside the story of Stax you walk through to get to it. The museum is larger (17,000 square feet) and more inclusive than expected -- it contains a circa 1906 Mississippi Delta gospel church preserved in its entirety and the dance floor from Soul Train. You can see Donald "Duck" Dunn's Fender Precision bass and the Hammond B3 organ Booker T. Jones used on "Green Onions."

Don't call the modest Motown exhibit an afterthought; it's more a sweet bite of dessert after a hearty meal of meat and potatoes. And we know some people -- maybe most -- like dessert best.

But it's not something to make a steady diet on.

PERSISTENCE OF PLACE

Place matters, and it means something that Stax Records settled into an abandoned theater at 926 E. McLemore Ave. Its founders, a self-described mediocre country fiddler and bank employee named Jim Stewart and his sister Estelle Axton, had first opened Satellite Records in a barn-like building in Brunswick, Tenn., in 1957. They soon discovered it was -- in addition to being a lousy venue for recording -- too remote to attract talent. So Axton took a mortgage out on her house to move the operation into Memphis and work commenced on remodeling the old Capitol Theater. They christened the new venture Stax Records, the name coming from the first two letters of their last names.

Stewart, along with Axton's husband and son and future legend Chips Moman (who after serving as Stax's recording engineer and house producer would go on to work with the Box Tops, Elvis Presley, Aretha Franklin, Bobby Womack and many others) worked on refurbishing the space, hanging acoustical drapes Axton had sewn and building a control room on what had been the theater's stage as well as a riser for the drums. They threw down a few carpets and had some baffles hung from the ceiling.

The result of this minimalist approach to soundproofing was a very "live" room with an inherent reverberation effect more akin to a concert hall than a typical recording space. This was further complicated by the fact that the theater's sloping floor was never leveled, because Stewart didn't want to spend the money to do so. This resulted in the studio having no surfaces directly parallel to one another, another factor that complicated and deepened the sound.

Not only did the studio become a major player in the Stax sound, the neighborhood itself was uncommonly populated by talent. Many of the area kids who were drawn to the Satellite Records store Axton opened in the lobby ended up contributing to the Stax sound. Booker T. Jones, a 16-year-old who lived within a couple of blocks of the studio (who would go on to lead the Stax house band, the Memphis Group, which released its own instrumentals under the name Booker T. and the M.G.s) hung out there after school and on Saturdays.

Dunn, the legendary bassist who later played with Jones in the MGs, remembers seeing Jones in the shop wearing his ROTC uniform. While Dunn didn't live in the neighborhood, he frequented the Satellite Records store because it carried rhythm and blues records and, unlike other stores, would allow him to browse and loiter. Guitarist Steve Cropper's first job at Stax was working the record store counter. William Bell was a neighborhood kid when he was recruited to sing backup on one of the label's earliest hits, Carla Thomas' "Gee Whiz."

The record store served as a kind of reference library for the musicians who played in the studio and a venue where tracks could be test-marketed and focus-grouped. Axton would play fresh recordings for local kids, and some records were shelved or rerecorded based on their feedback. Songs from rival companies would be played and discussed, deconstructed and reverse-engineered by players meaning to steal their trade secrets. The Satellite Records store was where most of the musicians who became Stax listened to Motown.

But as much as they absorbed, they didn't copy. The Stax sound was a different kind of beat music. Like Motown, it was flavored with R&B and inflected with gospel, but tied to something elemental and earthbound. Stax is a simplified sound, one that's brilliantly suggested by the label's logo of a hand, with its fingers poised for snapping. Stax is as basic as a heartbeat, without the airiness -- the ride -- of Motown soul. Motown tends to glide while Stax tends to bite. The aural space is different. Stax is lower, more guttural.

Motown soul is effortless, Apollonian, angelic; Stax soul is sweaty, Dionysian, earthy.

PRACTICAL MAGIC

Stax soul is the result of practical magic, starting with dictatorial drummer Al Jackson Jr., who decided on the tempo and locked it down, even when the other players -- especially Dunn -- thought his feel was a little slow. ("Al was always right," Dunn would later concede.)

Jackson had been a bit of a prodigy who had played with his bandleader father's swing group when he was 5 years old. He played with Booker T in jazz trumpeter Willie Mitchell's group and Booker T brought him to the attention of Dunn and Cropper, who decided they needed him in their band. But Jackson figured he could make more money playing live than doing sessions, so he demanded a weekly salary -- and got it.

Jackson's playing is as key to the Stax sound as Booker T's organ, Cropper's guitar or Dunn's bass or the signature Memphis Horns, who fulfill the function of backup singers on many of Stax' biggest hits. Jackson keeps straightforward, uncluttered time on the songs by vocal artists like Otis Redding, while on the MGs' instrumentals he sometimes intricately interlocks with the lead instruments, displaying a virtuosity normally held in reserve. While he was famous for his timekeeping ability, he's not a metronome. He subtly varies the phrasing and voicings -- the crispness -- of his beats and obtained his signature sound by stripping down the grooves, allowing notes to hang and decay in the air. He placed his wallet on his snare drum to dampen its sound and rarely, if ever, opened up his high hat cymbal.

"We used to basically keep the cymbals out of most of the songs," Cropper told Rob Bowman for the 2004 book Soulsville, U.S. A. "We thought the cymbals were offensive. Demographically we were told that research [showed] that girls bought 70 to 80 percent of the records and, if a guy bought one, he was usually buying it for his girlfriend. We thought that women's ears were a little more sensitive and that they didn't like cymbals so much, so we tried to keep them way down in the mix almost all the time."

STAX IN BLACK AND WHITE

It is worth mentioning that many of the essential figures in the Stax story -- Stewart, Axton, Moman, Dunn, Cropper and songwriter/producer/multi-instrumentalist Terry Manning -- are/were white folks. Booker T. & the MGs and the Memphis Horns were integrated. That this was happening in the highly segregated city of Memphis -- where a few years before Sam Phillips had famously found in Elvis Presley a white artist who had co-opted the codes of black performance style -- shouldn't be lost on us.

In 1965, Al Bell -- a black native of Brinkley -- joined Stax. Over the next three years he rose to become executive vice president and shared an office and, pointedly, a telephone, with Stewart. More than a mere executive, Bell became the driving force in the company, writing songs and producing albums. After Otis Redding died in a plane crash in December 1967, and Stax lost its distribution deal with Atlantic Records (and many of its most important artists), Bell almost singlehandedly ramped up the company's production in order to build up its back catalog. He signed the Staple Singers and Johnnie Taylor.

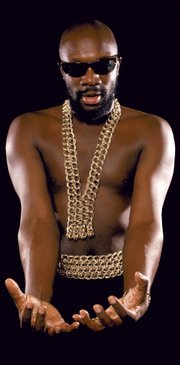

Bell bought Axton's share of the company and became co-owner in 1968 and had a few more good years as Isaac Hayes came into his own as a solo artist and movie star, an era commemorated by Hayes' Cadillac Eldorado rotating on a stage deep in the Stax Museum, which stands on the footprint of the old studio. With a white fur-lined interior, television, refrigerated bar and 24-carat gold detailing on the exterior (including the windshield wipers), the car was custom-built for Hayes in 1972. According to its little sign, it cost $26,000.

But it wasn't enough. Hayes eventually lost the car in bankruptcy. And Stax was done by 1975, a victim of a lousy distribution deal with CBS, changing tastes and maybe a little too much ambition on Bell's part. In a video in the museum, Cropper says the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. at the nearby Lorraine Hotel where the Stax musicians hung out and played cards and where Cropper wrote "In the Midnight Hour" with Wilson Pickett and "Knock on Wood" with Eddie Floyd, killed Stax as well.

"Before then, there was no black and white coming through the door," Cropper says. It was just musicians. But after that, they couldn't help but see race.

For a time after the label closed, the Stax building was used as a soup kitchen. It was torn down in 1989.

It was painstakingly replicated beginning in 2001. They even re-created the sloping floor.

Email:

blooddirtangels.com

Style on 10/16/2016