The number of children in the foster-care system is at a record level in Arkansas because caseworkers are removing more children from homes immediately upon investigation and judges are ordering removals against the recommendations of caseworkers, according to a report released Tuesday.

But Gov. Asa Hutchinson, who said he requested the report to provide insight into why the number of children in state care has rapidly increased and what could be done about it, said there were no clear answers.

"We continue to look at how we reverse this trend" -- if it needs to be reversed, he said in an interview late Tuesday. "If the reason is that there's more neglectful parents, and there's more child abuse, and there's more drug use in the home, then we have to protect the children."

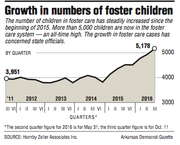

What is certain is that the number of children in the state's care has continued to increase. On Tuesday, 5,178 children were in the foster-care system. The state never had topped 5,000 children before this year. Between 2012 and 2014, 3,800 to 4,000 children were in foster care.

A child-welfare case begins when a report of possible abuse or neglect is made to the Child Abuse Hotline. Cases are investigated by the Children and Family Services Division or, in more serious cases, the Crimes Against Children Division at the Arkansas State Police.

A child can be removed for up to 72 hours without court approval. A child can be removed and placed in foster care, left in the home with an open protective-services case or voluntary services put in place, or left with no case open or services put in place. If a child is removed from the home, a judge must decide whether the state can continue to have custody and where the child should live.

The report, by Hornby Zeller Associates of New York, doesn't make clear whether more abuse is occurring or whether changes in policy or practice have accelerated significantly the child removals.

The report did say about 22 percent of child removals are "potentially" unnecessary, and it called for increased communication and cooperation among various entities. That percentage had increased over time, according to the report. Valid child removals must involve "an imminent safety threat to the child" and no "reasonable" alternative.

In separate interviews, Rep. Kim Hammer, R-Benton, and Sen. Alan Clark, R-Lonsdale, said they felt "vindicated" by the report. The two are co-chairmen of the Joint Performance Review panel, which has been investigating child removals and the agency that oversees them and provides caseworkers, the Children and Family Services Division.

Clark said the report echoed months of investigation by the committee -- particularly a finding that some children had been removed from their families without just cause.

"My first reaction is amen," he said. "It's just such a relief that they can't say anymore that it's not just that crazy senator from Lonsdale."

He renewed a call for increased oversight over the Children and Family Services Division.

"I just wish every legislator and the governor was getting every call that I'm getting," he said. "Even in the cases where people are guilty, we could just handle it so much better."

But the governor said the word "potentially" in the report made meaningless its claim about unjustified child removals.

"What does that even mean? Whenever you're exercising judgment, there's always the potential you make the wrong judgment," Hutchinson said. "I was not helped a great deal by that."

The report identified several causes behind the "potentially" unjustifiable child removals, as well as other problems.

In some cases, child-welfare investigators see themselves as "law enforcement officials rather than social workers," according to the report.

There's little communication between specialized investigators and caseworkers, who must look after the children after they're removed, according to the report. The caseworkers report that "investigators sometimes remove children who are not facing imminent danger and could be monitored in the home via a protection plan."

Protection plans are not used as much as they could because of legislation sponsored by Rep. David Meeks, R-Conway, according to the report.

Act 1017 of 2015 required the Children and Family Services Division to submit all protection plans for juvenile-court approval. But, according to the report, courts are more likely to place a child in foster care than the agency.

"Workers described the court's view of plans with words such as 'ineffective' and 'a joke,'" the report states. "Multiple supervisors and Area Directors reported that protection plans often fail to survive the court's scrutiny, with one supervisor commenting, 'If you consider using [a protection plan], you might as well take the kid into care.'"

The agency essentially can't stand up to judges because of the inexperience of caseworkers, according to the report. The agency is suffering from a "marked loss of experienced field staff."

Caseworkers have to contend with "pressure from the courts to make more removals, legal restrictions prohibiting [Children and Family Services] from diverting children from foster care by arranging for relatives to care for children, and high-profile cases that tend to make caseworkers and supervisors risk-averse," the report said.

The state should pass a law to allow parents to designate an appropriate caregiver, with the agency's approval, without the child entering foster care, according to the report.

Clark said that solution is "almost too common-sense for government" and he would be happy to introduce a bill to the recommendation's effect.

Hammer said there isn't just one cause behind the foster-care increase, but the report indicates that the investigation by the Joint Performance Review is on the right track.

"I think it's like a hundred-piece puzzle and every piece has its contribution to the complete picture," he said.

According to the state's transparency website, the Department of Human Services paid Hornby Zeller Associates $5.3 million in fiscal 2016.

Amy Webb, a spokesman for the department, said the report was included in an ongoing contract with the company and did not cost any additional money.

In an interview, Mischa Martin, the Children and Family Services Division's director, questioned many of the same parts of the report as the governor.

She said the report focused on subjective factors, focused on Sebastian and Pulaski counties as opposed to the whole state, and that about the same number of children entered the foster-care system in 2007, 2009, 2010 and 2011 as in 2016.

"We have not seen a huge spike in the number of children entering the system," she said.

Martin said she's looking at why children aren't exiting the system more quickly. For example, caseworkers have been burdened by the increasing number of children under their supervision and are not processing the cases as efficiently as they used to be able to, she said.

Regarding working with the courts and communication between caseworkers and investigators, she said everyone needs to be on the same page. She said she had reached out to the Administrative Office of the Courts to see how she could be a better partner.

"We need to have a common vision," she said. "That vision is twofold -- to protect children and to strengthen families."

Of the potentially questionable child removals, Martin said it's complicated.

"In every case, we want to make sure that children come into foster care as a last resort," she said. "Our cases are not always black and white."

A Section on 10/12/2016