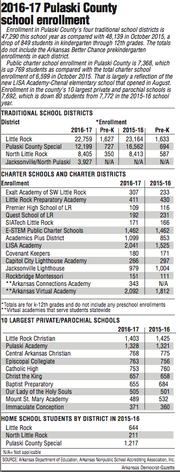

The Little Rock School District's kindergarten- through-12th-grade enrollment is down by 405 students to 22,759 in a year that has seen significant redistribution of students among schools and school districts in Pulaski County.

The Little Rock district remains the state's largest district, according to data from the Arkansas Department of Education for October 2015 and October 2016, but the Springdale School District in Northwest Arkansas, with 21,527 students in kindergarten through 12th grade, is growing annually and catching up.

Elsewhere in Pulaski County, the North Little Rock School District's enrollment is stable at 8,405 this year, down just slightly from 8,413 the previous year.

The Pulaski County Special School District's kindergarten-through-12th-grade student count in October was down from 16,562 to 12,199. The size of that decrease, however, is an anomaly that reflects the separation of the new Jacksonville/North Pulaski district from the Pulaski County Special system. That detachment became official July 1.

The new Jacksonville/North Pulaski School District's baseline-year student count this year is 3,927.

Enrollment in Pulaski County's independently operated, publicly funded charter schools and charter school systems showed a one-year increase of 769 students since last year, moving from 6,599 to 7,368.

The gain for the 12 charter schools or charter systems in Pulaski County is largely fueled by the opening in August of LISA Academy-Chenal, an elementary school just off Bowman Road in west Little Rock. The Chenal campus is the third campus in the LISA Academy system.

The 405-student drop in the Little Rock district's enrollment all but assures a decrease in state financial aid to the district in the 2017-18 school year. State per-student aid to a school district in a particular year is based on the previous year's enrollment. Specifically, the funding is based on the average enrollment in the first three quarters of the previous school year.

Any decrease in state aid because of enrollment declines would come at the same time that the state-controlled Little Rock district is adjusting for the scheduled end of $37.3 million a year in state desegregation aid.

That longtime special desegregation aid is being paid this school year and next school year, but it will end after the 2017-18 school year, according to the terms of a 2014 settlement agreement in a 34-year-old Pulaski County school desegregation lawsuit.

Little Rock Superintendent Mike Poore is conducting a series of evening community meetings to exchange ideas with the public on possible budget cuts for the district in the coming school year. The proposed cuts to be finalized in early 2017 would total more than $10 million in a budget of about $300 million.

"We are not anticipating having to make deeper budget cuts," Poore said last week about the loss of students on top of losing desegregation aid.

Already on the table are proposals to close or repurpose five of the district's more than 40 campuses: Carver Magnet, Wilson and Franklin Incentive elementary schools, Hamilton Learning Academy and Woodruff Early Childhood Education Center.

The district is also anticipating savings from discontinuing the busing of interdistrict transfer students to other districts and from streamlining bus service for special-education students and students participating in extracurricular activities.

A third area targeted for savings is in staffing within the central administration, and in middle and high schools so that classrooms are closer to the state limits of one teacher per 25 students.

"It means -- the whole staffing piece -- we have to really make sure we manage it well," Poore said last week about ways to compensate for student-generated state aid. "If we do a good job getting to that $10 million mark -- including the current staffing number around the $3 million mark -- we should be in good shape."

"Obviously, you always try to budget conservatively," Poore added. "We are trying to be much more aggressive throughout this fall and into the spring of recruiting students and being much more intentional about that than we have in the past. We hope that will have an effect."

Those efforts include encouraging prospective families to tour schools before making enrollment decisions.

"If we can get them into our buildings and let them walk around, we feel like we have a really good chance of them saying 'Wow, this is a good school culture, there's good teaching going on.' That's what we are trying to do," he said.

Registration for the 2017-18 school year for those who will enter pre-kindergarten and kindergarten, and for students who want to enroll in magnet schools that have arts, math and science, or international studies themes, or the Forest Heights STEM Academy will be Dec. 5-16.

Enrollment data for the Little Rock district's new Pinnacle View Middle School shows a total of 222 students, consisting of 103 blacks, 91 whites, 19 of Asian heritage, five of Hispanic heritage, and four of two or more races. A federal court challenge to the opening of the school centered on the possibility that the school's enrollment would be overwhelmingly white.

LISA Academy-Chenal, Pulaski County's newest charter campus, opened with 540 pupils, 266 of whom are black, 73 white, 112 Hispanic, 71 Asian, and 18 who are either of other races or are multiracial.

The student enrollment patterns in Pulaski County -- with its mix of traditional public school, open-enrollment public charter schools and private schools -- are the subject of a five-part study by the University of Arkansas at Fayetteville's office for education policy.

"School integration has been a contentious policy issue in Little Rock since the 1950s," the introduction to the series begins. "Recent charter expansions have raised questions about the current level of integration in public schools (charter and traditional) in the Little Rock area."

The different parts of the study examine broad changes in school enrollment in Pulaski County, and the demographics and academic performances of the students switching among different kinds of schools.

A sample of the findings from the study -- which cover 2008-09 through 2013-14 school years -- show:

• Enrollment in traditional public schools in Pulaski County has declined by 18 percent in the past 30 years. Charter school enrollment now represents about 10 percent of students in Little Rock's metropolitan area.

• More than 10,000 students have transferred between traditional public schools and charters in Pulaski County in the past six years.

• All students moving from traditional public schools into charter schools enter schools with lower concentrations of poor students, as demonstrated by their eligibility for free or reduced-price meals.

• There is no evidence that students transfer into schools with higher concentrations of students of their own race.

• Students move into schools with similar academic performance as the schools they left.

• Poor students are underrepresented, and black students are slightly underrepresented among students moving from traditional public schools in Pulaski County to charter schools.

• Public school students in the Little Rock metropolitan area are more likely to attend a racially integrated school than a socioeconomically integrated school. No more than 38 percent of students attend socioeconomically integrated schools. Up to 50 percent attend racially integrated schools, with "integrated" defined as reflecting the overall makeup of the overall student enrollment in the county.

Gary Ritter, founder of the office for education policy, said he was surprised that only a small fraction of all students who move out of the traditional public schools in the Little Rock School District go to charter schools.

Typically, he said, about 2 percent of those who attended the Little Rock district in one year have left the capital city district the next school year for a charter school, while 3 percent go to other public schools in Arkansas, 3 percent go to the adjoining Pulaski County Special or North Little Rock districts, and 7 percent leave the state's public school system -- which means the students have left the state, enrolled in private schools, signed up for home-schooling, died or have been incarcerated.

"Clearly the biggest slice we can no longer find in the data," Ritter said is the 7 percent. "It seems that a lot of energy is spent on concern about how are we going to keep the LRSD up and running and keep the budget going if we are losing all these kids, and there is great focus on the relative handful of kids going to charters. It ends up that if we stop kids going to charters entirely, LRSD would lose 13 percent of students per year [who were in the district the previous year] instead of 15 percent a year."

Sarah McKenzie, executive director of the office for education policy, said the study contradicts the perception that charter schools in Little Rock and across the nation draw higher-performing students from traditional schools.

"What we found is that kids are generally transferring to [charter] schools that are similar to what they left, and that their performance was average for the [traditional] school that they left. They weren't the highest-performing kids at their schools, in general.

"The one difference we did see was in terms of poverty rates," McKenzie said.

"Kids who left traditional public schools in Little Rock for charters transferred into schools that had lower overall poverty rates," McKenzie continued. "But we didn't see a difference in terms of demographics or achievement. That was interesting to me. I thought people would choose schools on higher achievement. There is some other mechanism that people are using in their decisions to transfer schools. It's not about going to schools with more kids that are like them or schools that are higher-achieving. There is something else."

Those unspecified reasons, she said, could be safety, convenience, faculty personalities, or academic or extracurricular opportunities, but the study did not go into that.

The link for the office for education policy and its publications is: officeforeducationpolicy.org.

Another facet of student enrollment in Pulaski County is home-school students.

In Arkansas, a total of 19,229 students were home-schooled in 2015-16, the most recent year for which numbers have been compiled by the Arkansas Education Department. That was 4 percent of the state's 476,049 non-home-school enrollment, according to the Department of Education. The largest numbers of home-school students are in Pulaski County Special, 1,217; Bentonville, 932; Rogers, 674; Little Rock, 644; and Springdale, 556.

The percentages of students home-schooled last year was as high as 13.4 percent. That was in the Yellville Summit School District. Guy-Perkins, Jasper, Mountain View, Mulberry-Mt. Pleasant Bi-County and Searcy County school districts had home-school student counts in excess of 10 percent of their enrollments.

There were 2,072 home-school students residing in the Little Rock, Pulaski County Special and North Little Rock districts.

Additionally, a total of 842 people received General Educational Development, or GED, certificates in Arkansas during the 2015-16 school year, including 46 in Pulaski County, according to state figures.

SundayMonday on 11/27/2016