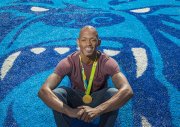

There stands Jeff Henderson, clad in patriotic blue, inside Olympic Stadium in Rio de Janeiro. It's Saturday evening, Aug. 13, at the finals of the 2016 Summer Olympics long jump competition. Henderson, 27, is in fourth place in the competition -- on the cusp of a medal -- as he prepares for his final jump.

DATE AND PLACE OF BIRTH: Feb. 19, 1989, North Little Rock

My pre-race ritual: I eat a banana for breakfast every time I compete. I have to have a banana. I always pray to God when I wake up. That’s always.

Favorite place I’ve visited: Bermuda

My most prized material possession: Besides the gold medal?

If I could race one famous person, it would be: Carl Lewis.

My favorite character trait in people is: Honesty, mostly. If they are honest and they are funny? You’re good in my book.

My pet peeve is: Bad smells. That’s probably the biggest thing. People are very, very ripe in athletics.

The one thing I will not eat is: Ribs, probably. I ate some ribs once that weren’t cooked all the way.

Always in my fridge you’ll find: Water, fruit and chocolate milk. I love chocolate milk. Organic chocolate milk tastes so much better than the regular chocolate milk.

My favorite junk food is: Peach cobbler. If not that, I love Chick-fil-A.

One word to describe me: Interesting

He bends his upper body forward at the waist, wiggles his fingers down low over the long jump track runway. The McAlmont native then rocks his body up, pivoting on his left foot, and stretches backward with his full body, jiggling his fingers again, before returning to a hunched-over position.

Then, he pulls his body back again, but just as it seems he's returning to a bow, he's off. Legs gliding, arms pumping, picking up speed. His strides quicken, his head comes slightly up, his legs start to blur.

A last step, a spring and blast off. Up, into the Rio sky, arms windmilling, legs pedalling the air. It's like he's attempting to fly. And flying he is, for barely more than a second, but it must seem like an eternity up there, soaring through the Rio night.

And now he's falling, and he tucks his torso over his thighs, almost touching his white Adidas-encased feet, before thumping back to the sandy earth, landing 8 meters and 38 centimeters from where he launched. It's nearly 27 feet and 6 inches from lift-off.

He springs from the sandy pit while the crowd roars. Henderson's 8.38-meter jump is 1 centimeter more than the longest jump of South Africa's Luvo Manyonga, the event's leader until Henderson's jump.

Henderson knows it's a long jump when he hears the crowd, but when his jump length flashes on the screen at Olympic Stadium, that's when he grasps he is in first place. And with two jumpers behind him, he realizes he has earned a medal of some sort.

Henderson celebrates for a minute. He pauses. He then watches the next two jumpers fly through the air. Neither beats his mark.

A centimeter probably doesn't mean much to most people. It's a tiny unit of measurement, basically the width of a No. 2 pencil or a little more than the depth of an iPhone.

So, a centimeter is so small it's almost negligible.

Not for Henderson, though. For him, a centimeter -- in an athletic endeavor where centimeters matter -- is "everything." Being 1 centimeter better than Manyonga meant a gold medal in the long jump for Henderson at the Rio Olympics, making him the first American man to win a gold in the long jump since Dwight Phillips in 2004.

"It doesn't matter how you win or how much you win by, as long as you win," Henderson says. "As long as you win."

Looking back on that August night, Henderson says that when he was on the podium, with the gold medal around his neck, "it felt like I wasn't there."

"I knew I was there," he says. "Al [Joyner] and some other coaches were there yelling very, very loud. That's how I knew. It just felt like I wasn't there. There were no emotions."

Joyner was an NCAA All-American at Arkansas State University and a 1984 Olympic gold medalist in the triple jump. He's also a USA Track & Field High Performance Olympic coach and Henderson's coach.

Before Henderson's final jump, Joyner offered some encouragement and advice. The key word in the exchange was "execution."

"I told him, 'If you execute what you need to do, I'm going to be happy, but you're really going to be happy,' because on any given moment Jeff Henderson can probably set the world record," Joyner says.

The Rio gold medal jump wasn't a world record, but Rio also was only the beginning for Henderson, Joyner says.

"He has the X-factor, that extra, that unknown to the point where if anybody could put it in a case, everybody would buy it," Joyner says.

"He's special. I don't know how great he's going to be, but I know he's going to be great."

GROWING UP ON THE TRACK

The truth is, football is Henderson's first love. Or, as he describes it, his passion. So much so that before the U.S. Olympic Trials in July at Hayward Field in Eugene, Ore. -- where Henderson won with a leap of 28 feet, 2¼ inches -- Henderson tried out with the Kansas City Chiefs.

Henderson was one of 67 players at the Chiefs' rookie mini-camp in May, running routes as a wide receiver and trying to impress the coaches.

He didn't make the team, but he's looking for another shot, at another receiver position. At 6 feet and about 185 pounds, Henderson says he's a slot receiver, a position where his shorter stature and speed come in handy.

"The wide receivers were way taller," he says. "I didn't have a chance to use my speed and hands. I didn't have a decent chance to show them what I could do on the field."

Football is a sport Henderson grew up with. The youngest of Laverne and Debra Henderson's five children spent his youth running around with a football with neighborhood children in tiny McAlmont in northeast Pulaski County, competing in youth football and playing for the Sylvan Hills High School Bears.

Henderson says he was a pretty good receiver, with good hands, a good route runner, and well, he was quick.

The quickness was natural, Henderson says, but he was never really fast until high school, when he started focusing more on track and field. His senior year, he exploded, running faster and jumping farther.

Rocky Fawcett, Henderson's high school track coach, says the athlete had tremendous natural gifts to begin with. "Once he discovered the weight room, he took off from there," Fawcett says.

Henderson won the long jump at the 2007 Arkansas Activities Association Class 6A state high school track and field championships and the 2007 Arkansas Meet of Champions high school meet, where he also placed second in the 100 meters.

"It came easy, even though I hate running," Henderson says. "No one wants to feel that pain. It hurts me once I'm done. The start is always easy, but the finish is like, 'Argggh.'"

LaConda Watson, the chief executive officer of the Boys & Girls Club of Jacksonville, watched Henderson race for years, first meeting him through Team Elite Track Club, a local track club that Henderson joined when he was a young teenager. She doesn't remark too much on Henderson's athletic talent. What she appreciates about the man is who he is off the track.

His manners are impeccable, Watson says. His attitude is likewise spotless. "Quiet," "modest," "polite" and "respectful" are just a handful of descriptors Watson uses when discussing Henderson.

Still, that athletic talent was noticeable, and Henderson nurtured his athletic ability, Watson says.

"He always went out and gave his best effort," she says. "He is such a hard worker. He set a goal for himself, and he would reach that goal."

Henderson struggled with attention deficit disorder and his grades were too low for major college track programs, so he first attended Hinds Community College in Raymond, Miss., where he won three National Junior College Athletic Association long jump national titles in 2008 and 2009 (outdoor and indoor), and one in the 400-meter relay.

He then attended Florida Memorial University in Miami Gardens before transferring to Stillman College in Tuscaloosa, Ala., where he won the NCAA Division II title in the 100 meters and the long jump in 2013 and was named an All-American.

Graduating from Stillman in 2013 with a degree in education, Henderson moved to San Diego, where he began training at the U.S. Olympic Training Center in Chula Vista, Calif., just southeast of San Diego.

Joyner became his full-time coach, with Henderson focusing exclusively on the long jump. It's his job.

"I was always fast in the 100 and 200, but I'm not fast enough," he says. "It's hard to compete for world when you're running a 10.1 or 10 flat. You got to run at least a 9.8 or 9.7, 9.9 to compete with them. Gosh, come on guys. You're killing me here."

A 10-second 100-meter dash is basically running at a little over 22 mph. It's still just a few steps too slow to be world class. With the long jump, though, Henderson could blend his speed with his leaping ability. It was a perfect combination.

He won the USA Track & Field Outdoor Championships in 2014, then last year won a gold medal at the Pan American Games in Toronto.

Technique is key in the long jump, and Joyner has been instrumental in honing Henderson's long jump procedure.

"The long jump is all a rhythm," Henderson says. "The rhythm is always the same thing. It's almost like an airplane. You're slowly, gradually building up speed until you take off at the end."

Once in the air, the goal is simple -- go far.

Joyner also has sharpened Henderson's mental approach to the long jump.

"He focuses mostly on challenging the athletes mentally because that's all it is once you're in the professional game," Henderson says. "Everyone has the talent to be great, but in their heads, they're always going crazy. If you are mentally strong, and then are athletically talented, no one can beat you because no one can really get in your head."

THE LOVE OF A SON

Laverne and Debra weren't in Rio that night. Debra, whom Laverne met in high school, was diagnosed with Alzheimer's disease about a decade ago. She is bedridden in their McAlmont home.

But Henderson's parents watched that fateful night on TV. And Laverne was part of a group of about 125 family members, friends and supporters who greeted Henderson when he arrived at Bill and Hillary Clinton National Airport/Adams Field on Aug. 17, gold medal in hand.

The days between Henderson's final jump and coming home were a whirlwind. There was an appearance on the Today show, and newspaper, TV and online interviews.

But Henderson was ready to see his mother and show her his gold medal.

"She's close to my heart," he says. He wants to give her things that insurance can't give her and make her life as comfortable as possible. He has become involved with the Alzheimer's Association, even playing a key role in the Alzheimer's Association, Arkansas Chapter's recent Walk to End Alzheimer's fundraiser in Little Rock.

Henderson greeted top fundraisers, listened to their stories and shared his own mom's fight with Alzheimer's.

"His recent [fame] has brought a lot of attention to him, so he helped us encourage people to participate in the walk, just to bring greater awareness about the cause," says Susan Neyman, executive director of the Alzheimer's Association, Arkansas Chapter. "We saw a nice spike in participation. He was very approachable, very genuine, and has a really great and caring heart."

The walk -- the organization's biggest fundraiser -- raised $150,000, Neyman says.

Henderson's local renown also led to him being selected as the grand marshal of Little Rock's annual Big Jingle Jubilee Holiday Parade this Saturday in downtown Little Rock.

While the celebration over Henderson's win continues, he's turning toward the 2017 track and field season, and, beyond that, the 2020 Summer Olympics in Tokyo.

He spends most of his time in Southern California, training seven days a week, making sure he's eating well (chicken, fish, fruits and organic juices mostly) and sleeping well. The training is sometimes eight to 10 hours a day, seven days a week.

He relaxes by watching scary movies, with Insidious and Insidious: Chapter 2 being favorites. Henderson is also working on a clothing line, titled JH Brand. Clothes that are "about being comfortable in your own wear," he says.

Plus, he wants to give the NFL another shot.

His primary focus is on Tokyo, where he hopes to fly briefly and defend his gold medal. Joyner expects Henderson to be there with more long jump victories in between. In fact, a lot more.

"I have a saying, 'What God left out of you, I can't put in you,'" Joyner says. "He has a gift. He has an amazing gift.

"I think he's going to be a legend of the sport. He's a champion. This is just the beginning. ... Now he knows how to be a champion. It's going to be pretty interesting to watch over these next [Olympic games] to see what this young man can do, because right now he has figured it out and that's a big problem for his competitors."

High Profile on 11/27/2016