PARKIN -- American Indian artifacts from a long-vanished culture are the primary attractions at Parkin Archeological State Park. But a restored 20th-century building sheds fascinating light on much more recent life here.

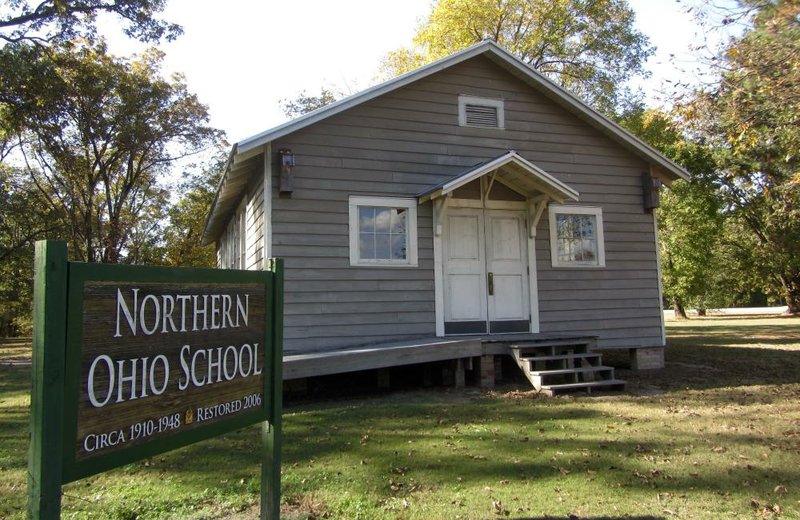

It's the one-room Northern Ohio School, attended by black pupils from about 1910 until 1948 in the lumber-mill community aptly known as Sawdust Hill. The town occupied much of the acreage extending over the prehistoric village of Casqui, thought to have been visited by Spanish explorer Hernando De Soto in the summer of 1541.

Until the middle of last century, the majority of Arkansas youngsters were taught in mainly rural one-room schoolhouses like Parkin's. Relatively few of these relics remain standing, but Northern Ohio School was saved at the northern edge of the state park after a lucky discovery described on a sign at the location.

After the school closed 68 years ago, a local family used the building as a hay barn. The property was bought in 1959 by the Ott family, who "transformed the old 'barn' into a home by portioning rooms and designing a living space. A carport and additional rooms were added through the years, completely disguising the one-room school. It was used as a residence well into the 1990s, when it was bought by Arkansas State Parks."

As the sign explains, "The restoration of this historic structure almost did not happen. When preparing to demolish the house, a unique discovery was made -- the Northern School was inside the walls. Plans for demolition were canceled, research began, and a plan for restoration was developed."

Inside the building, visitors see the classroom as it appeared on most any given school day between 1936 and 1948. The teacher's desk sits below the blackboard at the head of the class, facing eight tables and benches with room for five students each. Lunch pails are among the objects on display, along with two wood-burning stoves.

"Rural education in the Delta was no easy task for students or teachers," another sign reminds visitors. "There were many obstacles to overcome, such as weather, walking distances and family responsibilities. Plus, being an African-American school, students and teachers were often given used, worn and substandard materials. This made getting an education and graduating difficult."

The restored schoolhouse is just off the park's three-quarter-mile Village Trail, which skirts the St. Francis River. Part of the trail runs parallel to the moat evidently dug by Casqui residents sometime between the 11th and 16th centuries as a defense against warring neighbors.

Dirt from the moat may have been used to create the mound whose remains rise near the river bank. It is believed that the mound, flat-topped and pyramidal in shape, served as the base for the house of the village's chief. It has been reduced in size and altered in shape over the past 500 years by treasure hunters and erosion.

A 12-minute video shown at the visitor center asserts that Parkin "is one of the most significant archaeological sites in the United States." At the time of De Soto's visit, Casqui's population was perhaps 2,000. Villagers lived on the 17-acre site in wattle and daub buildings around the chief's mound. The village apparently was abandoned in the late 16th century.

Casqui's inhabitants were part of the so-called Mississippian culture. There were once dozens or more similar villages in eastern Arkansas, but most were destroyed by erosion, farming and careless artifact digging in the 19th century. Casqui was spared that fate by the 1887 establishment of Parkin town, which prevented cultivation by farmers before the advent of the Sawdust Hill community.

On exhibit at the visitor center is an array of prehistoric objects excavated here since the 1960s by the Arkansas Archeological Survey, a unit of the University of Arkansas. The work has been done in cooperation with the Arkansas Department of Parks and Tourism.

Among the eye-catching displays is a quiver made from a bobcat's skin and lined with a hollowed-out tree branch to hold the arrows. Another object hints at a sense of humor among some Casqui residents. It's a clay pot decorated with two figures perched on the rim across from each other. The exhibit's caption suggests that the scene depicts "a hunter gazing wistfully across at a rascally rabbit. A potter may have been poking fun at an unsuccessful hunter."

Parkin Archeological State Park, at the junction of U.S. 64 and Arkansas 184 in Parkin, is open 8 a.m.-5 p.m. Tuesday-Saturday, 1-5 p.m. Sunday. Admission is free. For details, visit ArkansasStateParks.com or call (870) 755-2500.

Style on 11/15/2016