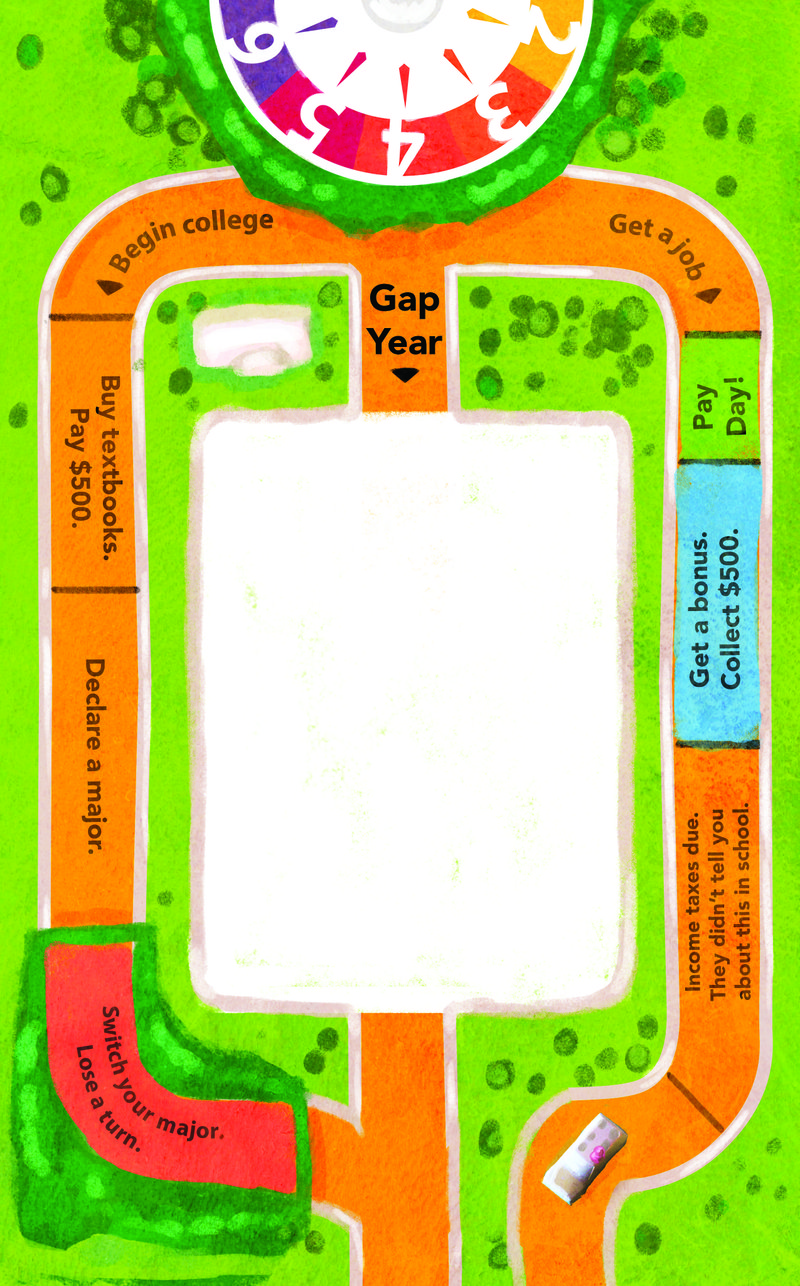

Beyond the classic board game created by Milton Bradley Co., for generations, the game of Life has been a well-worn but limited path after completing high school. The next move? Find a job, join the military, marry and become a full-time homemaker, or enroll in some form of higher education or trade school.

Recently, an increasing number of high school graduates, including one who calls this nation's White House her home, are venturing off those well-traveled routes to blaze new trails.

Malia Obama, eldest daughter of President Barack and Michelle Obama, is taking a "gap year" before beginning Harvard University in the fall of 2017. In England, where the gap year is more common, Prince William and Prince Harry both took time off from school during the early 2000s.

The one-year hiatus between high school and college, during which students typically travel, volunteer, study or work -- often abroad -- first became popular in other countries, but its acceptance is slowly, steadily increasing in the United States. And taking the year off is no longer a practice of just the financially privileged.

While a year-long international

program can cost as much as $30,000, more and more students are finding creative and frugal ways to have similar experiences.

Arkansas high school graduates are a slow-growing part of the trend.

Studying abroad outside the classroom

After excelling in his advanced placement studies and graduating from Prairie Grove High a year early, Roy McKenzie, 17, will spend what would have been his senior year living in Spain before beginning college back in the United States.

"Growing up in a small town like Prairie Grove, I was always looking for opportunities and making them for myself," he says.

When his cousin Maria, who lives in Spain, came to stay with McKenzie's family for a year between high school and college to have the American high school experience, he began thinking of doing the same with her family, and took classes at the University of Arkansas so he could graduate early.

"When I told people I was thinking about doing this they'd advise me not to rush my life away," he says. "I never wanted to rush. Instead, I was looking at whether the greatest value was going to come from me staying in high school doing the same thing for another year or finding some new opportunity."

His mom, Sarah McKenzie, executive director of the Office for Education Policy at the University of Arkansas, says her son has no set financial plan for his gap year.

"I don't know how it's going to work over there," she says. "He may have to play his guitar on the street corner. But that's part of him taking this year and what he's going to learn. I think it's such a great opportunity for the kids to see themselves in a new light, learn from different kinds of people than they've ever met before, and face some challenges on their own."

Realistic expectations

Her son says, "I feel like that is as much a part of the experience as the traveling itself. I'm not afraid of having to work some to make some extra money and then not working to take the time to travel. And I'm hoping it will be a trade-off between those two things. That is one of the major perks of my having family there. I'd be a little more worried if I was just going to be dropped off at the airport."

After returning from Spain, McKenzie will attend the University of Chicago, where he has a spot awaiting him.

Exact numbers aren't known, but The American Gap Association, a nonprofit group that accredits organized programs, estimates 30,000 to 40,000 students in the United States take time off annually, whether for a semester or a year. Gap year enrollment in the association's programs has increased every school year since at least 2006, growing by about 23 percent between the academic years of 2013 and 2014. Correspondingly, attendance at gap year fairs -- gatherings of organizations that facilitate programs for teens considering taking a year off -- across the United States has increased 294 percent since 2010, according to the AGA.

Some universities have developed gap year programs, with some deferring freshman year enrollment and/or financial assistance. All eight schools in the Ivy League system now consider a gap year to be a positive choice for freshmen. Harvard urges members of its incoming classes to consider it. The university's dean of admissions, William Fitzsimmons, along with two other school officials, even wrote an online essay espousing the benefits of a gap year.

Some who take a gap year volunteer with organizations such as AmeriCorps' City Year, which pays the students stipends to teach, or Global Citizen Year, which offers financial support to students who volunteer abroad, although admission to those programs is highly competitive (City Year only selects one in four applicants). Others sign up for mission work either in the United States or overseas, while others travel, work or combine experiences.

Supporters of the gap-year path believe students who have a meaningful, adventurous year between high school and college are more focused, mature and goal-centered when they do start classes. Skeptics worry the sometimes expensive alternative might cause students to detour off course and never make it to college.

Those considering a gap year are encouraged to have concrete plans for college afterward (preferably having deferred enrollment in a university), have a specific plan for how they will spend their year, and be at least partially financially invested (from their personal earnings and savings, not just their parents' money).

McKenzie says he believes a gap year experience gives students an additional perspective. "If you spend the year doing something really interesting and exciting, it has a lot of value and makes you a better person. For me, this is a chance to see a lot of the world while I can still have a very pure enjoyment of it.

"It is also a time for reflection, to figure out what you want to major in, enrich yourself, and whatever you experience, you can bring it back to your community."

As for organized gap year programs, his mother is dubious about how much the participating students gain from them.

"There's an industry of people who organize trips to places like Costa Rica or India, but it's still sort of supervised summer camp," she says. "The greatest thing about a gap year is that it gives kids a chance to be independent and make some choices on their own."

Ethan Knight, founder of American Gap Association, told The New York Times the gap year is when book smarts and street smarts intersect.

"If anything, it connects the theory that they've been exposed to over their many years of education to the reality of what's going on in the real world," he said.

Rooted in old-school tradition

While interest in a gap year is growing in Arkansas, there has been no flood of teens doing it.

Nancy Rousseau, principal of Little Rock Central High School, says while there may be more, she only knows of one senior from this year's graduating class who is choosing to take a gap year.

Cheryl Watts, a counselor at Pulaski Academy in Little Rock, says from her experience, the gap year hasn't caught on. She knows of no graduating seniors from her school planning a gap year. And through the years she has only seen a few students do it.

"Sometimes they may take off a year after they've started," Watts says. "I think if it was more socially acceptable in the United States, students would probably benefit from taking a year before college, but here, the thing to do is to go on to college."

The University of Arkansas at Fayetteville works to accommodate students wishing to take a gap year, says Suzanne McCray, associate professor of higher education, vice provost for enrollment and dean of admissions.

"We do allow students to defer their admission and defer scholarships and federally funded financial aid for a year as long as we understand what that gap year is and is some kind of planned activity," McCray says. "We've had students go on mission trips, Rotary scholarships and study abroad. We are certainly very flexible. We want students to have exceptional experiences and encourage that, as long as they're not attending another university domestically.

"But we don't have a lot of students who do this; usually two or three a year," she says of the freshman class, which last year was about 4,900 students.

Girl on a mission

Lauren McLemore, 18, of Maumelle, recently graduated from Central Arkansas Christian Academy in North Little Rock and was accepted by several colleges for the fall. Instead, she'll take a year-long mission trip overseas with a gap year organization.

"I will reapply in August," she says of the schools that accepted her. That same month, she'll leave for a two-week training camp out of state with Adventures in Missions' World Race program. In October, she'll leave the country with about 50 others.

"We will be in India, Malaysia and Zambia spending three months in each place," McLemore says of the program, geared for those ages 18 to 21.

"My initial thoughts were 'Your dad's not going to be happy about this,'" says Lauren's mother, Sherri. "He and I both know Lauren is very smart and could get a lot of scholarship money for college, but she just wanted a break from 'traditional' school."

Sherri adds that she is concerned for her daughter's safety but feels confident in the organization's preparation of its participants.

"Lauren has a heart of gold, so for her, missions overseas is the perfect gap year. ... This trip is one where God's nature gives you peace and that is how I feel. I couldn't be more proud of her."

A different kind of elective

Several years ago, after graduating from Little Rock Central High, Blake Rutherford was accepted to Middlebury College in Vermont. Since the college's year doesn't begin until February, he spent the interim as a "gap semester" working for Bill Clinton's 1996 presidential campaign and then the Presidential Inaugural Committee.

"For me, a gap half-year was an extraordinary experience," says Rutherford, now living in Philadelphia, where he is a lawyer. "From the things I learned to the people I met -- many of whom remain friends 20 years later -- taking some time away from academic life gave me some space to breathe, experience and grow in ways that were necessary and meaningful, personally and professionally, as an 18-year-old.

"I think it's good to take some time and do something that matters to you, whatever that may be. College is there and will be there a semester or a year later."

His father, Skip Rutherford, dean of the Clinton School of Public Service, agrees. "Several of our students come through AmeriCorps' City Year program, where they have taken a gap year either before they started as undergraduate or in the middle of their undergraduate, so I'm also familiar with it from that perspective."

Before the concept of a high school-college gap year became popular, it was often a practice of new college graduates to work a few years before returning for graduate school, Skip Rutherford says. "A lot of our students have come in with professional experience. So the gap year is taking that model down to the undergraduate level."

Rutherford is a proponent of students taking time off, "particularly during presidential election years, encouraging people to take some time off and experience it because for some, it's a once in a lifetime opportunity."

But, he says, it's not for everyone. "I think it is for someone who is ready, focused and determined -- it's an individual choice and an individual opportunity."

Style on 06/14/2016