"... In order correctly to define art, it is necessary, first of all, to cease to consider it as a means to pleasure and to consider it as one of the conditions of human life. Viewing it in this way we cannot fail to observe that art is one of the means of intercourse between man and man."

-- Leo Tolstoy,

“American Made: Treasures from the American Folk

Art Museum”

Through Sept. 19, Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art, 600 Museum Way, Bentonville

Hours: 11 a.m.-6 p.m. Monday, Thursday; 11 a.m.-9 p.m. Wednesday and Friday; 10 a.m.-6 p.m. Saturday-Sunday; closed Tuesday

Admission: $10 for “American Made,” regular admission to the museum is free

Information: crystalbridges.org or (479) 418-5700

What is Art?

BENTONVILLE -- Wandering amid the 115 or so works that comprise "American Made: Treasures from the American Folk Art Museum," you might wonder what the (largely anonymous) artists whose work is displayed would make of this quiet, contemplative space. What would they think of seeing their products -- shop signs, samplers, weather vanes -- removed from the clatter and dust of the enterprising world and set like jewels beneath muted lights in climate-controlled rooms?

The exhibit, the first folk art show mounted at Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art, draws from the collection of the American Folk Art Museum in New York, offering what Stacy Hollander, chief curator and director of exhibitions at the New York museum, calls an "alternative art history" of our still young country. And the artifacts may be displayed to better advantage here than they would be in the New York museum on Manhattan's Upper West Side.

I've been to that museum several times and told Hollander I expected many of the works in the current exhibit to be familiar. Instead, I only recognized two or three. She explained that the New York museum's gallery is only large enough to allow a small portion of the museum's collection of more than 7,000 works to be exhibited at any given time.

What's been assembled at Crystal Bridges is sort of a greatest-hits collection, a survey of the creative output of ordinary early Americans. It's touching and inspiring that such dedication to craft and quality should be expressed by people whose lives -- by our lights -- were difficult and largely devoted to securing the necessities of survival.

FOR ALL INTENTS

There is a school of thought that holds that all art comes from intention, that what separates the snapshot from the photograph is simply the will of the artist to make art. Some will even try to tell you that the meaning of any work of art is precisely whatever the artist intended it to be, regardless of what may be read into it or how inscrutable it might seem to the observer.

There is nothing inscrutable about a quilt or a weather vane, and there is obvious intention behind these objects. But their makers by and large did not intend for them to become art -- whoever carved that sheep that's hanging from the ceiling could not have imagined that someday it would be installed inside a museum. But there it is, removed from its original rural context, sacralized in a gallery. It is beautiful, a work of delicate craftsmanship informed by careful observation, a fantastic work of reportage. It hangs as a sheep would hang, in resigned dignity, belted about the middle, its head and neck drooping, gravity sucking either end down into a gentle C shape.

But is it art?

It is now, no matter how its unknown carver might have scoffed at the idea. He intended it as a practical sign, something that might inform the illiterate. So did the artisan who made the tragicomic giant tooth to alert the suffering to the presence of a dentist. Weather vanes were obviously made to indicate the direction of the wind, something that would be important in a weather-dependent agricultural society. Quilts were made to warm beds; whirligigs were toys meant to amuse and delight.

Even decorative articles like paintings -- portraits and landscapes -- were often made to convey information, to certify social position and standing. On the American frontier, hobbies were rare and extremely dear. Few could afford to indulge the impulse to, as Tolstoy put it, consciously communicate their inner feelings to others. There simply wasn't time.

But time is what we have, and by the end of the 19th century some members of the European and American upper classes had already begun to appreciate and collect utilitarian examples of the simple creativity of common folk. Some of this was no doubt driven by the modernist movement, which sought distance from the purely representational standards of classical art. (Some people reacted to Impressionism by embracing the plain aesthetic of a bygone era.)

In 1924, Polish-born American sculptor Elie Nadelman and his wife, Viola, had announced their intention to open their Museum of Folk and Peasant Arts in Riverdale, N.Y. The same year saw the first folk art exhibition in America at New York's Whitney Studio Club (later to become the Whitney Museum of Modern Art). By 1926, examples of folk art were being offered for sale in Antiques magazine, and in 1931 the first gallery to exclusively offer folk art -- Edith Halpert's American Folk Art Gallery -- opened in New York.

In a pamphlet written to accompany an exhibit at Harvard University in 1930, the founders of the Harvard Society for Contemporary Art (undergraduates Lincoln Kirsten, Edward M.M. Warburg and John Walker III, all of whom went on to become important figures in 20th-century American culture) attempted to define the term:

"By folk art we mean art, which springing from the the common people is in its essence unacademic, unrelated to established schools, and generally speaking anonymous."

As far as it goes, the definition fits, though most of the work displayed at Crystal Bridges also conveys an ineffable quality, a directness that connects the long dead and practically unknowable artist to the viewer. Some of this may be due to the context: If you remove any workaday artifact from its quotidian setting, dust it off and set it in a case it's likely to strike you as something alien and possibly beautiful. Part of what we human beings do is project and imbue meaning into things -- we lend our cars and appliances personalities. When you examine the intricate cross-stitching of a sampler made by preteen Sally Hathaway more than 200 years earlier it's not hard to correlate what must have been her experience with one's own.

"When you look at folk art, you're being invited into someone's life in a very visceral way," Hollander says.

"Invited" is one way to look at it. There's an unguarded quality in many of the artifacts on display here, and a certain confidence that none of the makers were interested in playing any high art games with identity. There's nothing oblique or obscure about these works. Still, there's a quality of spying in the experience, for these artists didn't think of themselves as such. They couldn't have imagined their work receiving this kind of scrutiny.

They didn't think they were doing anything extraordinary. They didn't think they were special creatures.

SELF-RELIANCE

And the thing is, they weren't.

Sure, there are some examples of portraiture in the exhibit that evince a certain professionalism and exploit some of the advantages that an imaginative medium had over early photography. But the skills on display here were once common skills. What we call "art" was not considered beyond the ken of ordinary folks. Ladies made quilts, girls made samplers, men applied themselves to making things both solid and winsome. It's not so much that the creators were self-taught -- no doubt many of the skills displayed here were handed down through generations -- but that they were self-reliant.

"I read the other day some verses written by an eminent painter which were original and not conventional," Ralph Waldo Emerson wrote in his famous essay on the subject from 1841. "The soul always hears an admonition in such lines, let the subject be what it may. The sentiment they instill is of more value than any thought they may contain. To believe your own thought, to believe that what is true for you in your private heart is true for all men -- that is genius."

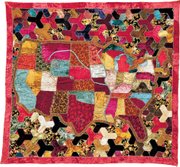

The articles on display in "American Made" are more than works of studied craft. They have a vigor and a unity of purpose. They are some of our best examples, masterpieces found among an allotment of quality. There's a vibrancy in a stunning map quilt of the United States as it was constituted in 1886. Made of scraps of silk and cotton, it hums with prideful power.

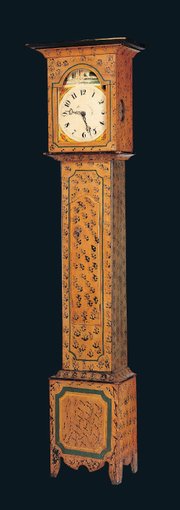

Other items may be of more historical than aesthetic interest. The monumental 8-foot tall hollow copper weather vane in the likeness of the Delaware Indian leader Tammany, said to be the largest surviving example of its kind, is iconic and an essential feature of the exhibit. But it's no more powerful or affecting than the tiny folded paper soldiers and horses that, circa 1850, a young boy made for his amusement.

When Crystal Bridges' curator Mindy Besaw says, "These are truly their treasures which they entrusted us with," she's talking about the collaboration with American Folk Art Museum. But I hear it differently. This is the way Americans lived, this is what they left us. These humble acts of beauty.

Email:

Style on 07/24/2016