He drives his red pickup off the paved road and onto a dirt path before coming to a stop at a lake.

The heat index has already climbed above 100 degrees on this June afternoon, making it almost unbearable to leave the air conditioning. So Verlon Abram, 65, stays in the truck and points to the 22-acre lake that looks like it has always been there but was built only a few years ago.

The lake is part of Abram's desire to make a living from the land of his family's farm in the Wilburn community in Cleburne County. He moved back to the farm after he retired from the Army in 2006.

Abram initially planned to raise cattle. But when drilling rigs and other heavy equipment began rolling into the community, he realized there was an alternative use for his 773 acres.

A crush of companies arrived in north-central Arkansas in the mid-2000s eager to pull natural gas from the Fayetteville Shale, a formation that stretches across the state to the Mississippi River.

The nation was on the verge of a shale boom that would change the American energy landscape.

In Arkansas, it offered a gold-rush opportunity for people like Abram, and thousands of jobs and wealth for local communities.

But it didn't last.

The energy companies' success at extracting natural gas from shale soon became their undoing. An oversupply of gas pushed prices to record lows. That led to layoffs, bankruptcies and meager royalty checks.

The glory days of the Fayetteville Shale are over. The main drillers are gone. What remains is sobering. Businesses have closed. Once-bustling highways are mostly empty now, and equipment sits idle along the roadsides.

ENERGY EXPLORATION

The early days of the Fayetteville Shale exploration were highlighted by discovery of new geology and development of new technology. There was a lot of optimism about the gas-producing potential of the area, but there was also a hefty dose of skepticism.

This was north-central Arkansas, after all, where acres of green support dairy and cattle farms. There had never been energy exploration there.

Then, while Southwestern Energy Co. was drilling for natural gas in the Arkoma Basin, the potential of shale natural gas was discovered in Arkansas. Until this time, the Barnett Shale in north Texas was the only commercially producing shale formation in the United States.

Realizing that the shale rock in north-central Arkansas was similar to that in the Barnett play, Southwestern Energy started buying acreage across the state in 2003. The next year, the company drilled its first Fayetteville Shale well in Conway County.

Other companies, including Chesapeake Energy Corp. and XTO Energy Inc. -- a subsidiary of Exxon Mobil -- followed, looking for gas in the shale. Chesapeake Energy eventually sold its Fayetteville Shale assets to BHP Billiton Ltd. in 2011.

"How significant it is in the history of shale exploration: Prior to the Fayetteville Shale, only the Barnett was commercially producing," said George Sheffer, Southwestern Energy's vice president of operations for the Fayetteville Shale. "The Fayetteville Shale proved the Barnett wasn't a fluke because it proved another shale was productive."

To extract the natural gas from the Fayetteville Shale, energy companies coupled hydraulic fracturing, or fracking, with horizontal drilling. The technique, used in the Barnett play, allows companies to reach more of the gas locked in the rock formation.

Fracking involves blasting water, sand and chemicals underground to break apart the dense rock, releasing trapped natural gas and oil.

As the energy industry realized that fracking was the key to unlocking the oil and gas trapped in shale formations, it became the go-to method from Texas to North Dakota to Pennsylvania, igniting the nation's energy boom and pushing the United States ahead of Russia and Saudi Arabia as the world's largest energy producer.

CHUMP CHANGE

Abram lives in a modest, double-wide mobile home on his property. Not far away is the farm's main house, a red-brick structure where Abram's daughter, a schoolteacher, lives with her family.

When gas companies approached Abram about leasing his property for drilling, he agreed to a lease of $25 an acre, plus one-eighth mineral royalties.

"If they offer me upwards of $20,000, they must be a gift from God," he recalled thinking at the time.

Looking back, Abram calls the terms of the deal "chump change" because landowners who waited to lease their properties received better payouts.

The first two natural gas wells built on his farm were behind his home. In the years since, six more have been built on that same well pad and another 25 throughout Abram's property.

"I refused to sell the old farm because of my attachment to it," he said. "I thought I would have to get into raising cattle to survive, but then gas exploration came."

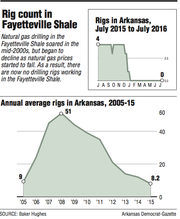

The Fayetteville Shale entered its heyday in 2008. That year as many as 60 drilling rigs worked in the formation. Natural gas prices ranged between $6 and $10 per British thermal units, and rose above $13 per Btu at least once.

Drilling activity reverberated throughout the local communities in numerous ways. It provided landowners new sources of income through royalty checks, offered new job opportunities, and generated millions of dollars in revenue for communities and the state.

The timing was fortuitous, community leaders say. As counties in the Fayetteville Shale region buzzed with activity, the global economy entered a recession.

"We were sheltered from much of the downturn in the economy," said Buck Layne, president of the Searcy Regional Chamber of Commerce. "The counties in Arkansas that were fortunate enough to have the Fayetteville Shale, their communities and counties were beneficiaries of income that was unexpected."

For the South Side Bee Branch School District in Van Buren County, the increase in revenue from the Fayetteville Shale allowed the district to pay for building projects and stop receiving state aid, Superintendent Billy Jackson said. The district replaced roofing, renovated classrooms, added a security system, bought iPads and computers for students, and hired specialists to help students with remedial studies.

"If the Fayetteville Shale had not happened, we would have had to have made cuts to keep operating," Jackson said. "It's allowed us to do things we were not able to do. The renovations are because of the Fayetteville Shale."

As new job opportunities started trickling in, energy companies discovered a problem. Since there had never been shale exploration in the area, few locals were qualified for the jobs the companies were looking to fill.

In 2006, Southwestern Energy partnered with the University of Arkansas Community College at Morrilton to offer a petroleum-technology program. The program had 30 students in its first year. By December 2015, 462 students earned certificates and degrees in the program.

For many graduates, the program offered a high payoff. They were able to enter an industry that was known for its high-paying jobs.

During the Fayetteville Shale's heyday, annual salaries for roughnecks in the gas fields were as high as $100,000 -- about 2½ times higher than what most jobs in the communities paid, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Personal income in some of the busiest shale counties increased during the drilling activity, rising gradually at first, then jumping between 2.7 percent and 4 percent in 2008, according to the U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis.

Some counties saw an even bigger increase in personal income. In Cleburne County, the jump was almost 8 percent in the one-year period, and in White County it soared 11 percent. While personal income in all of the counties dropped in 2009, it never reached previous levels, although it did increase in 2010.

"It was kind of like a windfall of cash that came into our community -- to the landowners," Layne said. "Most people working in the gas business were making very good money. ... It was a heyday. It was a good time here in White County and every county."

Some residents, like Abram, reaped benefits from the uptick in business activity and mineral royalty payments.

Abram found ways other than drilling to feed the drilling operations.

"I started selling them shale [to construct well pads]," Abram said. "I sold them lots of shale and lots and lots of water."

SEECO, a subsidiary of Southwestern Energy, built a second lake on his property to support its fracking operations and paid him for the use of the water

Abram built his lake about five years ago with the intention of selling the water to the energy firms. It cost $127,000 to build, and he recouped that expense within one year.

But use of the lake as a water source for the companies' fracking was short-lived. Federal regulations were implemented that required Abram to get a permit, and he said it became too costly to continue.

But, "the gas companies were good to me."

The money he received from the gas exploration allowed him to take his children and their families on European vacations and Mediterranean cruises.

"They have made me fairly wealthy," he said. "I'm not going to lie to you."

GOING BUST

As quickly as the Fayetteville Shale rose, it fell even faster. Drilling in the play began to decline in 2012 when natural-gas prices dipped below $2 per million Btus and struggled to rebound.

In response, the three main operators in the state -- Southwestern Energy, XTO Energy, and BHP Billiton -- moved their rigs to other U.S. shale formations that were rich in oil and natural-gas liquids, which are more profitable than the Fayetteville Shale's dry gas.

Local communities started to feel the effects. Workers began to lose their jobs, smaller oil-field service companies scrounged for work, and business activity -- from hotels to restaurants -- declined.

Despite the slowdown, hope for a resurgence remained. Many analysts and investors expected a rebound in natural-gas prices. A recovery in prices would revive activity in the Fayetteville Shale, they said.

But the Fayetteville Shale hasn't recovered.

By 2014, fracking had created an energy boom in the United States, providing record amounts of natural gas and oil. Supply of natural gas and oil worldwide exceeded demand and cut crude-oil prices in half.

From Pennsylvania to Texas, energy companies curtailed exploration to save money and have yet to fully recover.

All of the drilling rigs in Arkansas are gone. Most of the smaller oil-field service companies that had popped up in the shale area have disappeared. They either left for other states or went bankrupt, community and industry leaders say.

The University of Arkansas Community College at Morrilton ended its petroleum technology program, and layoffs have sent most gas field workers hunting jobs in other states.

Mark McLendon, who lives in Greenbrier, was laid off Dec. 17 by Schlumberger, an oil-field service company. Now he works for a fluid hauling company in the area.

"I've always said 'when it's good, it's good, and when it's bad, it's bad,'" McLendon said. "I've been doing this since 1995, and this is just one of those downturns.

"A lot of the local people from Arkansas thought they were just following a big, golden pile of work, and that's just not the case."

Local revenue from drilling activity also has declined. In 2015, the South Side Bee Branch School District received $4.6 million in local funding, down from $6.2 million in 2011, according to the superintendent.

He said the slowdown hasn't forced the school district to make cuts yet, but if it continues that is something the district will have to consider.

"We were the victims of our own success," said Danny Games, who was hired by Chesapeake in 2007 and now is deputy director of the Arkansas Economic Development Commission. "If the Fayetteville had been the last or next-to-last play, we would still have 60 to 50 rigs.

"We just found too much gas."

Many things have gone back to the way they were before natural gas wells were scattered across north-central Arkansas, but there is a sense of loss now that wasn't there before. The royalty checks that increased the standard of living for so many aren't as fat as they once were, and that's being felt throughout the region.

"My royalty checks have reduced by about three-fourths," Abram said. "I'm not selling any shale. When drilling stops, the construction stops."

Was it worth it -- to have the energy companies swoop in and then leave?

"It was to me," he said without hesitation.

"I may have wasted my money on frivolous things like vacation, but it's been good for me."

Information for this article was contributed by Emily Walkenhorst of the Arkansas Democrat-Gazette.

SundayMonday on 07/17/2016