It is silly to think bad people are incapable of great art.

To be an artist is to be reckless with the confidences and secrets of others. You have to be willing to use your mother's shame and your brother's waywardness, to allow your own darkness to bleed through. You have to be selfish or at least willing to put your work before the world. You have to be brave to be an artist, but you don't have to be good.

Instinctively we know this, so it doesn't shock us when we hear rumors or read news stories about how some artists misbehave. There is a comic, famous for his honesty, about whom sordid sexual rumors are flying. In his act, this comic -- my training makes naming him impossible despite the easy identification the internet offers, despite the chattering websites, for these are rumors after all -- talks about situations uncomfortably close to the things he is accused of doing. On stage, he is fearless and funny in a way that induces squirms, for his material suggests that we are all the same, that we all understand the impulses to which he refers and that to pretend otherwise is worse than mere hypocrisy, but somehow life-denying.

His work these past few years has been remarkable, the sort of transcendental comedy that gets called "genius." Yet if he has done the things he's alleged to have done, he is certainly not a good person. We are not shocked by this -- even if he denies the rumors (which he hasn't quite, although he has sensibly noted that all he can really control is work), he doesn't claim to be a wholesome figure. And maybe those of us who can't help but laugh are complicit.

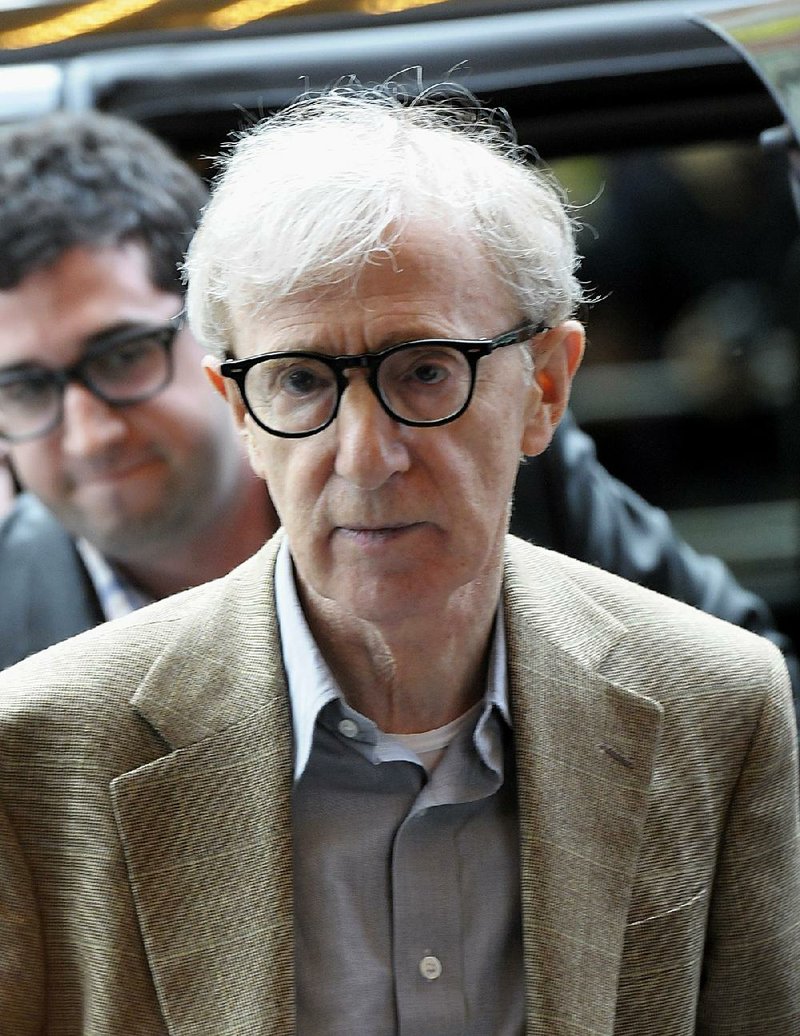

In this country we talk a lot about how people are supposed to be presumed innocent until they are proven guilty, but we all know it's not like that. There are stigmas attached to suspicion, not to mention arrest, indictment, conviction or confession. People are almost always willing to assume the worst if it fits in with the way they see the world. Of course dirty-talking comedians are perverts; of course presidential candidates are crooks. We are merciless in our judgments: Bill Cosby and Roman Polanski are rapists. Woody Allen is a child molester.

...

I still go to Woody Allen movies.

At least part of this is professional obligation, though Allen's movies don't typically screen for critics outside of major metropolitan areas. The last one I saw in advance of its opening was 2002's Hollywood Ending; I flew to New York to see it and to interview Allen. Those sorts of interviews, which consist of a few minutes in a hotel room, rarely yield much of interest because their whole purpose is to promote the movie, and most actors (Allen not only wrote and directed Hollywood Ending but played the lead role) are very good at winning empathy and staying on message. They can seem to be genuine while telling you exactly what they need to to enhance the commercial prospects of their films. I've done a lot of these interviews and remember only a few.

But Allen seemed extraordinarily candid and relatively unconcerned with how he might be portrayed in a newspaper in Arkansas. He came across as a serious and bright man who was very aware of his limitations as an artist. He did not consider himself a great director or writer and had no illusions about his onscreen persona. He worked a lot because he had the opportunity to work a lot, he had discovered that managing expectations and not blowing modest budgets were key to being allowed to make a movie every year. He said he was puzzled and a little dismayed that he didn't get more work acting in movies that he didn't write and direct -- he said he had never turned down an acting job. They just weren't offered very often.

He also seemed a terrible snob; he implied that he didn't expect anyone who lived outside the major Eastern seaboard cities of this country to really understand his films. He seemed peculiarly incurious about people unlike himself. He seemed very much like the character he typically plays, both in his own movies and on those rare occasions when he appears in others' films: the nebbish, the neurotic, atheistic, intellectual pessimist so horrified by the certain knowledge of his own extinction that he's driven to preoccupation with sex, work and the life of the mind.

I didn't care much for Allen, though he was pleasant enough. It seems likely he has acted monstrously toward people who trusted him -- that's what artists sometimes do. But he was kind and apparently candid. And I have enjoyed many of his movies. Unlike a lot of critics, I don't particularly prize his early "funny" movies like Take the Money and Run (1969), Bananas (1971) and Everything You Wanted to Know About Sex (1972); the first time I really took notice of Allen was for his work as an actor in Martin Ritt's The Front (1976), a black comedy set in 1953 at the height of McCarthyism.

Allen played a variation on his nebbish character in The Front; he starred as Howard, a scheming small-time bookie who is prevailed upon by his friend, a blacklisted TV writer, to sign his name to scripts in exchange for a percentage of the proceeds. The ploy is successful and other blacklisted writers seek out Howard, who gains a reputation as a principled artist -- in part because he becomes picky about the material to which he'll affix his name. Howard started demanding rewrites from his clients before submitting the scripts.

While Allen is terrific in the film, delivering a calibrated and very funny portrayal of a devious man who eventually develops integrity, not everyone was thrilled about the casting. At the time, Allen was still primarily known as a stand-up comedian and his presence was seen as detracting from the film's seriousness of purpose. (Director Ritt, writer Walter Bernstein and several members of the cast, including Zero Mostel, had been victims of the blacklist.) But The Front was an important movie, and Allen's speech at the end of the picture -- which you can find on YouTube -- is a classic.

The next year there was Annie Hall, a movie that's as entertaining as it is influential. It still holds up -- I watched it again last year in the company of a film critic who remarkably had never seen it and who holds no special admiration for Allen, and she was suitably impressed.

But it was Manhattan (1979) that turned me into an Allen fan, and when I was 21 years old I wasn't much bothered by the affair between middle-aged Isaac Davis (Allen) and 17-year-old Tracy (Mariel Hemingway). (I didn't see Allen's homage to Ingmar Bergman, 1978's Interiors, until after Manhattan, but I love that film as well.)

Allen's best filmmaking decade was the 1980s. He confidently absorbed the influence of Bergman, Federico Fellini, Luis Bunuel and the Marx Brothers into some startling original films (Stardust Memories, Zelig, A Midsummer's Night Sex Comedy, Hannah and Her Sisters, Another Woman, Radio Days, September, The Purple Rose of Cairo) that culminated in 1989's masterful (and underrated) Crimes and Misdemeanors.

Allen made some really nice movies in the 1990s. Mighty Aphrodite (1995), Sweet and Lowdown (1999) and Husbands and Wives (1992) would make a good run for almost any other writer-director. He has made good films this century -- Match Point (2005), Vicky Cristina Barcelona (2007), Midnight in Paris (2011) and Blue Jasmine (2013) among them.

Yet it has been 27 years -- since Crimes and Misdemeanors -- since he has made anything that could be considered great.

...

Cafe Society is the 48th movie Allen has directed.

Some of them are horrible failures -- The Curse of the Jade Scorpion (2001), Cassandra's Dream (2007) and Scoop (2006). (I retain a slight fondness for Hollywood Ending, which nobody else seems to like and which is sometimes cited as the absolute worst Allen film ever.) Others -- Whatever Works (2009), Anything Else (2003), You Will Meet a Tall Dark Stranger (2010) -- are barely remembered.

Yet I still look forward to every Woody Allen film. I still see them in theaters, rather than waiting for the (no frills) DVD. Like Allen, I have mastered the art of managing expectations.

And so Cafe Society is all right though I wonder why it exists. It is about what you ought to expect from one of his movies these days, an intermittently clever script, an overqualified cast, a character who is quite obviously a Woody surrogate behaving in Allen-esque ways. In this film, the role falls to Jesse Eisenberg, who earlier took on the role in 2012's To Rome With Love, a broad ensemble comedy that represents a recent low point in Allen's oeuvre.

Eisenberg, effective in other roles, seems stolid and mechanical here, in an odd way matching the peculiarly flat narration (supplied by Allen). Cafe Society is highly representative Allen -- if you're playing Woodman bingo, you can immediate cross off "older man/younger woman romance," "Los Angeles depicted as a vacuous cultural wasteland" and "nostalgia for Hollywood's Golden Age" off your card. It seems off that a movie set in the midst of the Great Depression should take absolutely no notice of economic desperation, a tone-deaf valentine to, uh, missed opportunities and settling for Blake Lively.

But as with a lot of Allen's work, there are redeeming moments. Kristen Stewart continues her run of remarkable turns, putting her Twilight days farther in the rear-view mirror. Jeannie Berlin and Corey Stoll contribute fascinating supporting turns. Somewhere deep in the script -- or at least in Steve Carell's subtle performance as hotshot Hollywood agent Phil Stern -- is an allegory about Jewish insecurity in the run-up to World War II. And the great Italian cinematographer Vittorio Storaro renders it all beautifully.

It's not enough, but it's not a collapse either. It's just another Allen movie. And that's the point. My main criticism of Allen as a filmmaker is that he has become too efficient -- he's able to finance and produce even his slightest ideas. If he made a movie every two or three years rather than every 10 months he'd wouldn't just be seen as a better director -- he'd be a better director.

We all need to be frustrated and denied our whims. We all need to be told "no" from time to time.

But if Allen is no longer one of my favorite directors, I'd like to think that has more to do with my intellectual evolution than my assessment of his character or even any fall-off in the quality of his work. I just don't think Allen is as clever or insightful as I did when I was younger.

He's amusing and, at his best, he can be coolly unsentimental as he strips away his character's illusions. But more and more often his work is suggestive of a depth that isn't genuinely there. In To Rome With Love, there's a moment when Alec Baldwin's character describes Ellen Page's sexually manipulative actress as a "self-absorbed pseudo-intellectual" who knows a line or two of poetry, the name of a philosopher or two, just enough to bluff her way past the gate.

More and more it seems that's the sort of moviegoer Woody Allen caters to -- a middle-brow poseur who has read a little Proust.

More and more, it seems that's the sort of moviemaker he has become.

Email:

blooddirtangels.com

Style on 08/21/2016