David Foster Wallace has a book coming out next month, his second posthumous volume after the 2012 essay collection Both Flesh and Not.

This isn't surprising, since publishing does not stop for death. Foster Wallace has fans. There will be buyers; his estate will benefit as well as a lot of people who do humble work. Death's the end of the personal universe, but the emanations of the deceased continue to echo and ring. The length of the reverberations is one way greatness is measured.

This book is called String Theory: David Foster Wallace on Tennis (Library of America, $19.95) and it is, as the title implies, a collection of five nonfiction pieces Foster Wallace wrote about the sport, all of which have been collected in other volumes. Its highest and best use might be as a gift for your tennis fan friend who is intrigued by Foster Wallace but who has never made it more than a few pages into Infinite Jest, which is set, in part, in a tennis academy.

I have a mild interest in tennis, one that peaked in the age of Ilie Nastase, Jimmy Connors and Bjorn Borg. I can claim I was the best racket re-stringer employed at Shreveport's Lorants Sporting Goods when I was in high school. I also played the sport for a while, never at a high level, though I invariably lost to some good club players who might have been about as good at tennis as Foster Wallace was, who might have encountered him on some Midwestern court in the late '70s.

Tennis seems deceptively simple to outsiders. On television it resembles a live-action version of the vintage computer game Pong, with the competitors moving back and forth, up and down, in the two-dimensional space of a screen. Because the camera foreshortens the court, you don't get a sense of the power or the speed of the game. You don't understand how high the top players hit it, or how a ball can dive and skid and skip. Lots of things look easy when you're ignorant.

Foster Wallace was on the tennis team at Amherst College, but not one of their better players. In the first essay in String Theory, "Derivative Sport in Tornado Alley," which originally was published as "Tennis, Trigonometry, Tornadoes: A Midwestern Boyhood" in Harper's Magazine in 1991, well before he was established as a major figure (eulogized by the New York Times' A.O. Scott as "the greatest mind of his generation") but after the publication of his alternately charming and disturbing first novel The Broom of the System (1987), he recounts his history in the game:

"Between the ages of 12 and 15, I was a near great junior tennis player. I cut my competitive teeth beating up on lawyers' and dentists' kids at little Champaign and Urbana country club events, and was soon killing whole summers being driven through dawns to tournaments all over Illinois, Indiana and Iowa. At 14, I was ranked 17th in the United States Tennis Association's Western Section ... fourth in the state of Illinois and around 100th in the nation."

Should we be impressed? Probably, though Foster Wallace, in an interview with public radio talk show host Leonard Lopate in 1996, would only cop to being something like the "4,000th" best tennis player in his age group in the country.

"I played real serious tennis when I was a child. I played it enough to feel like it was beautiful," he said. "I perhaps could have been somewhat better. One of the interesting things about playing competitive sports as a child is you confront your own limitations rather starkly at a certain point. For the first couple of years I was very good and regarded as promising, and then after I developed for two or three years it became very clear how good I was going to be, which was that I could probably be a good college player but I was never going to have professional potential or anything."

This is probably the most valuable lesson sports teaches those of us who aren't quite good enough to transcend our physical limitations. It really doesn't matter how big your heart is or how much you want something if there are others who are bigger, faster and have better hand-eye coordination than you do. Sports is where you discover how hollow platitudes are. We cannot will ourselves beyond some limit determined by genetics and our initial social condition. We can improve, we can get better, but most of us will never be Michael Jordan or David Foster Wallace.

Still, we beat on, boats against the current, yada yada.

Foster Wallace kept playing tennis.

"I kept playing but there's a difference between playing and training," he told Lopate. "The people who seriously, seriously play devote their lives to it. The way monks do. You don't date, you go to bed at a certain time, you eat certain ways, you practice 10 to 12 hours a day. The difference between practicing three hours a day and practicing 12 hours a day is everything. I never trained seriously after the age of 16."

At some point Foster Wallace understood that his command of the game was illusory. In "Tornadoes," he writes:

"In and around my township -- where the courts were rural and budgets low and conditions so extreme that the mosquitoes sounded like trumpets and the bees like tubas and the wind like a five-alarm fire, that we had to change shirts between games and use our water jugs to wash blown field-chaff off our arms and necks and carry salt tablets in Pez containers -- I was truly near-great: I could Play the Whole Court: I was In My Element. But all the more important tournaments, the events into which my rural excellence was an easement, were played in a different real world: the court's surface was redone every spring ... the green of these courts' fair territory was so vivid as to distract, its surface so new and rough it wrecked your feet right through your shoes, and so bare of flaw, tilt, crack or seam it was totally disorienting. Playing on a perfect court was for me like treading water out of sight of land: I never knew where I was out there."

I don't know how it was for Foster Wallace to know that his dream had receded, but there was recompense. As he told Lopate:

"As my interest in tennis waned, my interest in academics increased. I started doing my homework in high school and discovered that it was somewhat fun. And then in college I barely played on the team, because classes were a lot more interesting."

...

Probably all of the pieces collected in this 138-page volume are familiar to most Foster Wallace fans, but I had never read "How Tracy Austin Broke My Heart," which first appeared in the Philadelphia Inquirer in 1992 and was later collected in Foster Wallace's 2006 book Consider the Lobster and Other Essays. It is on the surface a sort of snarky review of Austin's then just-published autobiography Beyond Center Court: My Story (co-written by sportswriter Christine Brennan). It's an easy target, one you might consider unworthy of Foster Wallace's consideration. Rife with cliches and nonsense, the book serves as Austin's brief that she was actually disadvantaged -- that her family was "poor" despite her being immersed in a country-club lifestyle where all the Austin children got a new car on their 16th birthday.

"Stuff like this seems way out of touch with reality," Foster Wallace writes, "until we realize that the kind of reality the author's chosen to be in touch with here is not just un- but anti-real."

Yet the comedy recedes in the essay's third act as Foster Wallace considers the implications of the athlete's famous focus, of the ability to "withstand forces of distraction that would break a mind prone to self-conscious fear in two."

It might be a Zenlike nothingness. "How can great athletes shut off the Iago-like voice of the self? How can they bypass the head and simply and superbly act? ... It may well be that we spectators, who are not divinely gifted as athletes, are the only ones able truly to see, articulate and animate the experience of the gift we are denied. And that those who receive and act out the gift of athletic genius must, perforce, be blind and dumb about it -- and not because blindness and dumbness are the price of the gift, but because they are its essence."

...

The next three pieces are pretty well known. "Tennis Player Michael Joyce's Professional Artistry as a Paradigm of Certain Stuff about Choice, Freedom, Limitation, Joy, Grotesquerie, and Human Completeness," which originally appeared as "The String Theory" in Esquire in 1996, was previously collected in Foster Wallace's A Supposedly Fun Thing I'll Never Do Again (1997), and it is the first heavily footnoted piece in the collection. It's also brilliant, a classic piece of sportswriting that's a contender for the best tennis story ever written --a title often bestowed on the book's closer, "Federer Both Flesh and Not."

Between these two essays is a splendid piece of ethnographic reportage, "Democracy and Commerce at the U.S. Open," which was commissioned and edited by Jay Jennings, the Little Rock-based writer (Carry the Rock: Race, Football and the Soul of an American City ) and senior editor of the Oxford American.

Jennings' account of working with Foster Wallace can be found online at blog.hrc.utexas.edu/tag/jay-jennings/ and is worth a read. Jennings writes:

"In 1995, I contacted a young writer named David Foster Wallace to ask if he would come to the U.S. Open over Labor Day weekend and riff on the scene, not so much the one on the court but that going on all over the grounds of the National Tennis Center in New York."

The resultant story became "one of the longest (and best) Tennis magazine has ever run" though Jennings had to fight "to see that it was published as Dave intended it, footnotes, eccentric abbreviations and all. In the essay, after having spent only a few days there, he had crystallized all the annoyances, grievances, glories and grandeur that those of us who had been attending the event for years had observed but with more humor, sharpness and empathy: the 'felonious' price of the Haagen-Dazs bars, the 'big ginger beard' that made one of the ball boys look like a 'ball grad student,' and the 'mad crane' style of a 6'6'' player."

...

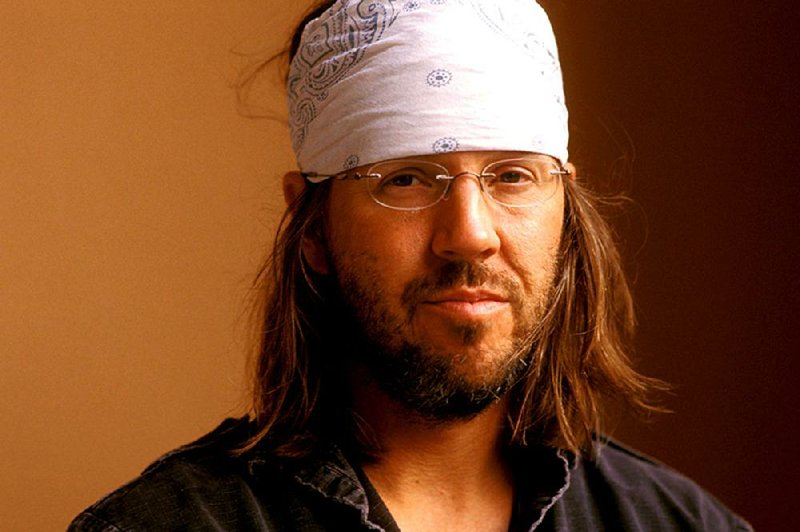

Foster Wallace's suicide in 2008 shook some of us, causing us to wonder: What does it mean when someone we perceive as smarter and luckier than most chooses to opt out? That life is mysterious and difficult and that we hold on to it too tightly at times? He seemed to just be getting started, and we mourned as much for words unsaid as the man we never knew. I felt some kinship with Foster Wallace, though he wasn't on a list of people I ever wanted to meet. I loved a lot of his work. Sometimes I felt jealous. Sometimes I felt awe.

Mostly I feel like we've lost something -- at the very least, a great sportswriter.

blooddirtangels.com

Style on 04/24/2016