MOUNTAIN VIEW -- Dan Kemp says he doesn't know the identities of donors to his winning campaign for chief justice of the Arkansas Supreme Court.

He cites the state Code of Judicial Conduct, which instructs candidates to "as much as possible, not be aware of those who have contributed to the campaign."

Yet those gaps in knowledge leave him in a quandary.

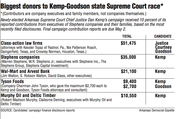

He wouldn't know, for example, that one of Arkansas' best-known business families -- Stephens of Little Rock -- and executives from Stephens companies contributed about $35,000.

Or that three other influential Arkansas business families and their executives -- Walton, Tyson and Murphy -- gave a combined $41,050.

Or that together, individuals connected with the four families' interests donated more than $1 of every $5 that the Kemp campaign raised.

Kemp also says he doesn't know who was behind an estimated $600,000-plus in campaign ads that appeared in the closing weeks before the March 1 vote.

Those ads, funded by "dark-money" donors, attacked his unsuccessful opponent, Courtney Goodson, a sitting Supreme Court justice elected in 2010.

Yet when Kemp takes the most powerful seat on the state's highest court in January, the state's Code of Judicial Ethics also requires him to disqualify himself from any case that involves a campaign contribution big enough to "raise questions as to the judge's impartiality."

What will Kemp do if big donors appear before him?

"It's a difficult situation," the judge said in an interview in his office last week. "I do believe we need to look at some possible reforms."

Change the rules

An Arkansas legislative committee and an Arkansas Bar Association task force are studying now whether the state should appoint rather than elect appellate judges -- along with other changes to judicial selection and campaigns.

Supreme Court Justice Karen Baker announced Thursday that the high court is forming its own Committee on Judicial Election Reform to review how best to improve public confidence in the state's judiciary.

Appointing rather than electing judges in Arkansas would require a constitutional amendment approved by state voters. A hearing Wednesday before the Arkansas Senate Judiciary Committee left legislators doubting that the measure has enough backing to go before voters this year.

Kemp says he understands the appeal of appointing judges, which divorces judges from campaign contributions. That's how the federal court system and those of several states operate.

"But we don't have that system right now," Kemp said. "There's no assurance the people are going to pass it."

In the meantime, Kemp wants to study new rules governing campaign contribution reporting and judges' decisions to disqualify from contributors' cases.

That includes judges knowing donors' names and the amounts given, information that's on the judges' own campaign contribution reports, which are posted online by the Arkansas secretary of state's office for the public to see.

"Instead of this Chinese wall that's supposed to shelter judges from that knowledge" of who their donors are, Kemp said, "let the judges know as well, just like the public does. And the judges can make a decision whether to recuse or not."

Kemp also wants to study what other states have done to establish a threshold of dollars or percentage of campaign contributions that would require a judge to disqualify from a case. In Utah, for example, a judge must recuse if he accepted more than $50 in the previous three years from any party involved.

"Arkansas can look to have that transparency in judicial elections, if we continue to have elections," Kemp said.

Another issue is the donors behind dark-money advertising.

The Judicial Crisis Network of Washington, D.C., bought more than $600,000 in last-minute ads attacking Goodson.

The advocacy group and other nonprofits like it don't have to disclose their donors.

But Kemp and other state and national legal observers are talking about whether state law -- in judicial races only -- could require groups like the Judicial Crisis Network to reveal contributors' names and dollars.

They point to a 2015 U.S. Supreme Court ruling in a Florida case that appears to sanction different campaign standards for state judicial races as compared with other political campaigns.

In Williams-Yulee v. Florida Bar, the nation's high court ruled that states can ban judicial candidates from personally asking supporters for campaign contributions.

Candidates for most elected offices regularly ask supporters for donations. But about 30 states, including Arkansas, forbid judicial candidates from making those appeals, saying it threatens public confidence in a fair and impartial judicial system.

If states can apply different rules in judges' races in that way, the thinking goes that they could require "dark-money" groups to register with election authorities for only judgeship races and disclose the donors.

A March 3 letter to Goodson's campaign supporters said she looked forward to working with Kemp, Gov. Asa Hutchinson and others "committed to ridding our judicial system of the corrosive influence of dark money."

If Arkansas wants stricter rules governing judicial elections, Kemp, Goodson and the justices who sit beside them on the state Supreme Court have more power to take that step -- and quickly -- than anyone else, legal observers say.

The state's high court adopts revisions to the state Code of Judicial Ethics.

The seven-member high court could decide by majority vote, for example, to set stricter standards for judges to disqualify from contributors' cases, said David Sachar, executive director of the state Judicial Discipline and Disability Commission.

The court could require candidates to know their campaign contributors and make that information available to case lawyers and the public.

"The Supreme Court could just change the rules," Sachar said. "They could do it themselves. That's my opinion."

Million-dollar race

The Kemp-Goodson race was one of the most expensive judicial campaigns in Arkansas history.

Kemp raised $342,149 in contributions through Feb. 20 and loaned his campaign $20,000, according to his most recent report filed Feb. 23. His campaign spent less than it raised -- $271,436. Final campaign contribution reports for Kemp and Goodson aren't due until May 2.

Goodson's biggest donor was the justice herself, according to her most recent campaign contribution and spending report filed March 15.

Her personal loans to the campaign hit $641,000. That dwarfed her $351,405 in contributions from others. Campaigns have 45 days after an election to raise money to retire loans or debt, elections experts say. Overall, Goodson's campaign spent $976,960.

Goodson's biggest donors included attorneys with three out-of-state law firms that have worked on class-action cases with her husband, Texarkana lawyer John Goodson. They gave $40,675 in the last 10 days before the March 1 vote, or about $1 in every $9 raised by Goodson's campaign, excluding loans, campaign finance reports show.

The three law firms were Kessler Topaz Meltzer & Check of Radnor, Pa. ($32,575); Crowley Norman of Houston, Texas, ($5,400); and Nix Patterson & Roach of Daingerfield, Texas ($2,700). The firms did not respond to questions.

Nix Patterson partner Cary Patterson of Texarkana, Texas, and family members donated an additional $10,800 to Goodson's campaign earlier this year, bringing her 2016 total from the three firms to $51,475, campaign finance records show.

Goodson's office did not respond to emails or phone calls seeking information about her campaign contributions.

The Kemp-Goodson race attracted national attention in part because of the Judicial Crisis Network's "dark-money" advertising.

Other circumstances have caused lawyers and lawmakers to look closer at Arkansas judicial elections, court observers say.

In January of 2015, former Faulkner County Circuit Judge Michael Maggio pleaded guilty to one count of federal bribery. Maggio admitted taking campaign contributions in exchange for reducing a jury verdict in a nursing home negligence case.

Reporting by the Arkansas Democrat-Gazette in January about major contributors to the six current state Supreme Court justices also drew legislative and legal experts' attention.

As a group, six law firms and their lawyers were among the largest contributors to the campaigns of the current elected justices, the newspaper reported.

The firms include the three big-donor firms to Goodson's campaign this year, plus two Oklahoma firms and Keil & Goodson of Texarkana. Goodson's husband is a partner in the Texarkana firm. All of the firms have worked together on multmillion-dollar class-action cases in Arkansas.

The six firms' total donations between 2006 and 2014 to Justices Goodson, Baker, Robin Wynne, Paul Danielson, Josephine Hart and Rhonda Wood campaigns topped $296,000, the newspaper reported.

Since 2008, the state high court has decided at least eight cases in favor of the Keil & Goodson firm and co-counsels who donated to justices' campaigns. A search of the Arkansas court system's online records did not find any Supreme Court cases in that period that the law firms lost.

Courtney Goodson recused from hearing her husband's cases, as required by state law.

Ethical tightrope

Kemp says the only state Supreme Court seat that attracted his interest was Position 1, chief justice.

In addition to deciding cases with the rest of the court, he likes the top job's administrative demands: dealing with legislators on issues such as presenting budgets, working closely with the director of the Administrative Office of the Courts to oversee the state's entire court system.

Among his priorities, Kemp wants Arkansas' public defender operation expanded so its average lawyer won't have to handle more than 500 felony cases each year, as it works now. (The American Bar Association recommends 150, Kemp said.)

He would like to see more drug courts for addicts, who often commit property, hot-check, forgery and other crimes. He's interested in domestic violence courts, patterned after drug courts, as a potential pilot project in Arkansas.

When he agreed to be interviewed, Kemp required that the newspaper not reveal to him the names of his campaign donors or the contribution amounts.

"I want to follow the canons of ethics," he said.

That meant the Democrat-Gazette couldn't ask what Kemp would do if a case involving the Stephens, Walton, Tyson or Murphy companies goes before him.

Instead, the newspaper asked him to imagine getting big campaign donations from a company like Apple, which did not donate to his race, and what he would do if an Apple case came before him on the Arkansas Supreme Court.

Kemp couldn't find an easy answer.

"You're kind of walking a tightrope to abide by the ethics canons and not be aware who your contributors are," Kemp said. "Yet when cases come before the court, are campaign donations going to be in the back of somebody's mind? That's something I'm going to have to face.

"That's what the current justices face now."

SundayMonday on 04/03/2016