Kevin Rodriguez is a 16-year-old U.S. citizen and the youngest of four brothers. Whether his family can continue to live with him in this country may depend on who becomes the next president.

RELATED ARTICLE

http://www.arkansas…">Arkansans await immigration case

His mother, Veronica Razo, crossed into the country illegally with his three older brothers before he was born. His family is a microcosm of the immigration debate, a window into where immigration law has been, where it is now and where it might go after a contentious election season that has spotlighted immigration policy.

Kevin Rodriguez's older brother, Erick Rodriguez, was deported in January because of a felony conviction for a fake Social Security card he used to get a job, illustrating the enforcement side of today's immigration policy.

The oldest brother returned to Mexico years ago rather than risk deportation. The third brother, Alan Rodriguez, has a permit to stay in this country under an Obama administration program whose legality is set to be argued before the U.S. Supreme Court this month.

The gulf between the sides of today's immigration policy is clear in the national debate over what to do with families like Kevin Rodriguez's.

The leading Republican presidential candidate, Donald Trump, began his campaign with a call for a continuous border wall with Mexico and a statement that many Mexican immigrants are rapists and drug-dealers. He and his closest opponent, Ted Cruz, have agreed all immigrants without valid visas should be subject to deportation.

"At some point, there is going to be a change because I think the American people are simply demanding it," said Sen. John Boozman, R-Ark., who has said tighter enforcement must come before any other reform. "Hopefully, we'll get a system where it's fair: You wait in line, you do what you're supposed to do and you're rewarded for doing so."

Democratic candidates Bernie Sanders and Hillary Clinton have called for a path to citizenship or legalization for many illegal immigrants, particularly for children and families such as Kevin's, and they have promised to go further in that aim than President Barack Obama.

"For us it has to be a comprehensive approach," said Mireya Reith, executive director of Arkansas United Community Coalition, which works for reform and to engage the immigrant population in their communities. An increase in the number of visas granted each year, for example, could make legal migration an easier endeavor, she said.

The ongoing refugee crisis in the Middle East and Europe and recent terrorist attacks there have thrown global border security into the political mix as well.

"The world is filled with a lot of people on the move," said Alan Kraut, a history professor at American University and fellow at the nonpartisan Migration Policy Institute. Immigration "is on everybody's tongue."

But all of the recent attention on the topic will come to nothing unless enough members of Congress unite to change federal laws, a tall order on such a contentious issue, political researchers said in recent weeks.

"You have everybody agreeing that there's a problem, but the perspectives on the solution are so different that that may mean we're just in for protracted attention, but little action," said Janine Parry, a University of Arkansas political science professor.

Kevin Rodriquez and his family are watching. Razo joked that the family should start saving money in case the side emphasizing security and deportation wins.

The youngest brother said he feels helpless as he waits to turn 21, when he can sponsor his family members for visas, which take decades to process and would require his mother to return to Mexico. Until then, he said, "they might get deported any second."

"I feel like I'm the only hope for them," Kevin Rodriguez said last month in the family's Johnson duplex. "I can speak out, basically, but I can't do anything."

Across the border

The family's story in the U.S. began in the early 1990s when Razo crossed the Rio Grande into McAllen, Texas. Back home in the central Mexican city of Irapuato, most of her money went to groceries, and the family lived inside four thin vinyl walls.

Razo had no resident family members in the U.S. to sponsor her legally, and if she had, her application probably would have been considered just in the last few years, according to the U.S. State Department's March 2016 visa bulletin.

"I see life very, very difficult here. It's not impossible, but it is more difficult for the majority of people," Enriqueta Razo, Veronica's sister, said in her home in Irapuato in December. "They lived with very little money."

Veronica Razo's sons grew up going to Fayetteville schools. In 2013, Erick and Alan Rodriguez requested and received Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals, the enforcement policy President Obama announced in 2012 after Congress failed to approve a similar program called the DREAM Act.

Deferred action allows immigrants who came to the U.S. illegally before they turned 16, lack a criminal record and meet several other requirements to apply for a two-year, renewable deferral of deportation, a work permit and a Social Security number.

Erick Rodriguez lost his protection after he was arrested in April 2015 for misdemeanor public intoxication, according to the Johnson police report.

Erick Rodriguez already had the 2014 felony forgery conviction for the fake Social Security card while he was awaiting valid Deferred Action documents to arrive.

The 2015 arrest caught the attention of Immigration and Customs Enforcement, which began the process to deport the now 22-year-old. He was detained at LaSalle Detention Facility in central Louisiana. Homeland Security Secretary Jeh Johnson in a 2014 memo said agents should focus on dangerous immigrants with felonies or multiple serious misdemeanors. "A felony is a felony," Immigration spokesman Bryan Cox said last year.

An immigration judge ordered Erick Rodriguez deported in December. After a wave to his family, he was moved to a facility in New Mexico, where he said helicopters carried in more detainees at all hours.

More than 235,000 people were removed from the U.S. in fiscal year 2015, down about 40 percent from the peak in fiscal 2012, according to ICE statistics. The Pew Research Center reports the number of immigrants here illegally also has fallen to about 11 million after the recession.

At midnight Jan. 7, authorities woke Erick Rodriguez and his fellow detainees, returned their regular clothes and made roll call several times, he said. After a guarded bus ride to El Paso, Texas, and a trip across the border to a Ciudad Juarez airport, Rodriguez arrived in Mexico City about 11 a.m.

ICE operates its own fleet of aircraft for removals because the deportees often fill entire flights, Cox said. Though Rodriguez's detention lasted nine months, the average stay in ICE custody from detention to deportation is about 30 days, Cox said.

Rodriguez traveled back to his birth city of Irapuato for the first time since he was a toddler.

"I kind of feel like a tourist, like lost and stuff," he said from his aunt's home in January. He plans to go back to school and get a good job, and he's staying in his cousin's old room. His older brother, Jonathan, lives about half an hour away.

Rodriguez said he was working on his Spanish, which he spoke with a noticeable American accent. He was also getting used to the traffic free-for-all in the city, where road signs and lanes are more a suggestion than a requirement. Even the fruit and meat tasted different and fresher in a city known for its strawberry farms, he said.

Enriqueta Razo, a certified nurse, said she told her sister, "'If he wants to continue studying, you finance him his career, and here he will have lodging and food.'"

Family members in Johnson are still adjusting to Erick Rodriguez's absence.

"Its definitely a very weird feeling," said Alan Rodriguez, 20, adding he usually avoids going into his brother's bedroom. He recently applied to renew his Deferred Action standing and, taking his brother's experience to heart, said he has been on his best behavior.

"I've been avoiding a lot of trouble; I've been thinking a lot before I act."

His mother said she didn't regret her illegal crossing despite her son's deportation.

"If you want to be someone in this world, you've already seen that you can do it here, and over there you have your only chance to do it," she said of her second son.

What comes next

The Razo-Rodriguez family's story, along with today's immigration debate, is intertwined with policies going back decades.

The country in 1965 discarded the national-quota system that favored European migrants in favor of a system emphasizing family ties and immigrants with needed job skills. It still had quotas, but they were tied to hemisphere instead of country.

The switch led to a surge of Latin American and Asian migrants. The law's requirement for a family sponsor in the U.S. was also part of the reason Veronica Razo decided against the legal option, and it sparked some of the earliest concerns about illegal immigration, said Kraut, the American University professor.

"Suddenly countries like Mexico, which had been sort of free-flowing back and forth across the border, had quotas," he said.

The Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act of 1996 also introduced local law enforcement agencies to immigration enforcement, said Elizabeth Young, director of the University of Arkansas immigration law clinic.

Two decades later, the Washington County jail ran Erick Rodriguez's fingerprints through a national database that alerted ICE to his arrest, an office spokeswoman said last year. The law also bans Erick Rodriguez from applying for a visa for 10 years.

The 1996 law was one of the last major changes to immigration policy, though not for lack of trying.

Reform attempts failed throughout George W. Bush and Obama's terms, often because conservatives weren't satisfied it did enough to beef up border security. One notable failure came in 2013 with the bipartisan "Gang of Eight" bill, which offered a path to citizenship along with more agents and surveillance along the southern border.

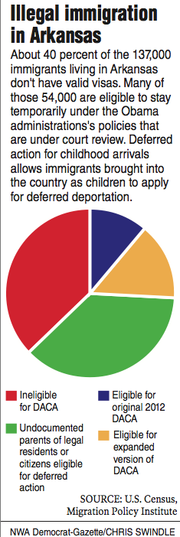

Arkansas and 25 other states sued the Obama administration in 2014 after it tried to expand Deferred Action to include more childhood arrivals and immigrants whose children are citizens or legal residents. A U.S. Supreme Court ruling on whether the expanded policy is valid could come this summer after this month's hearing.

Attempts to give some immigrants a means to stay failed because "no one's willing to take that step to expose themselves in that way politically," said Xavier Medina Vidal, a University of Arkansas professor of Latino studies and assistant professor of political science. Hispanic migration from the diverse Southwest into less immigrant-heavy regions such as the South in the past two decades prompted a backlash against reform that Trump and others are "reinvigorating," he said.

Kraut said "an enormous amount of economic pain" plays into today's controversy as well. Reports from the conservative-leaning Cato Institute and the more liberal Brookings Institution found immigration has little to no effect on wages or employment, but Kraut suggested the perception of a link persists.

"He (Trump) makes outrageous statements about Mexicans, he wants to bar Muslims -- all this is craziness, but what's not crazy is the sentiments that he's tapping into. There are people who have been seriously hurt by the recession and who have not experienced recovery," Kraut said.

Not all see Trump's views as outrageous.

Marguerite Telford, spokeswoman for the Washington, D.C.-based Center for Immigration Studies, which supports limiting immigration, said some immigrants without visas have assaulted and killed others. More must be done to deport them and keep them out, she said.

"We love the fact that it's being talked about, because when you talk about it, something might actually happen," she said last week. "It's not a question of whether we should have immigrants in this country -- obviously, of course, we should. We can control the numbers."

Most researchers interviewed were pessimistic that more leniency or enforcement will come of the heightened attention.

Any change also likely wouldn't be the final word in the debate, said Bill Schrekhise, an Arkansas associate political science professor specializing in public policy, pointing to the historical pattern of reforms every decade or so.

"The best we can hope for is it becomes a less contentious issue and we can move on to something else," he said, though even he added immigration could remain controversial indefinitely.

Others in the debate said they see hope for after the election. The office of Rep. Steve Womack, R-Arkansas, wrote in an email statement Obama's deferred action policies "diminished" the chance for real discussion, while a new administration might tighten the border.

"I do think something will happen if we get a Republican in office," Telford said, noting such a president can undo the deferred action policies. "On the Republican side, it has really resonated, and it has forced them (the presidential candidates) to make promises."

Reith, the Arkansas coalition director, said she also has hope for reform, though she added "a lot of healing will have to be done" after the presidential nomination and election process.

"This election race in general is one that's being led by extremes -- the majority of Americans aren't there," she said. A majority of Arkansans support a path to legalization with certain requirements, for example, according to the long-running Arkansas Poll survey done by the University of Arkansas. "We have not given up the hope that the majority of this country in favor of reform will prevail in the election."

For the Razo-Rodriguez family, hope has been tempered by experience.

"I believe that this country is full of good people willing to do something," Alan Rodriguez said. "What I've learned from Erick's case is we have to keep in mind the worst thing."

NW News on 04/03/2016