SACRAMENTO, Calif. -- California agreed Tuesday to end its unlimited isolation of imprisoned gang leaders, restricting a practice that once kept hundreds of inmates in segregation units for a decade or longer.

No other state keeps so many inmates segregated for so long, according to the Center for Constitutional Rights. The New York City-based nonprofit represents inmates in a class-action federal lawsuit settled on behalf of nearly 3,000 California prisoners held in segregation.

The state is agreeing to segregate only inmates who commit new crimes behind bars. It will no longer lock gang members in soundproof, windowless cells to keep them from directing illegal activities by gang members.

Until recently, gang members could serve unlimited time in isolation. Under the settlement, they and other inmates can be segregated for up to five years for crimes committed in prison, though gang members can receive another two years in segregation.

"It will move California more into the mainstream of what other states are doing while still allowing us the ability to deal with people who are presenting problems within our system, but do so in a way where we rely less on the use of segregation," Corrections and Rehabilitation Secretary Jeffrey Beard said.

The conditions triggered intermittent hunger strikes by tens of thousands of inmates throughout the prison system in recent years. Years-long segregation also drew criticism this summer from President Barack Obama and U.S. Supreme Court Justice Anthony Kennedy.

"I think there is a deepening movement away from solitary confinement in the country, and I think this settlement will be a spur to that movement," said Jules Lobel, the inmates' lead attorney and president of the Center for Constitutional Rights.

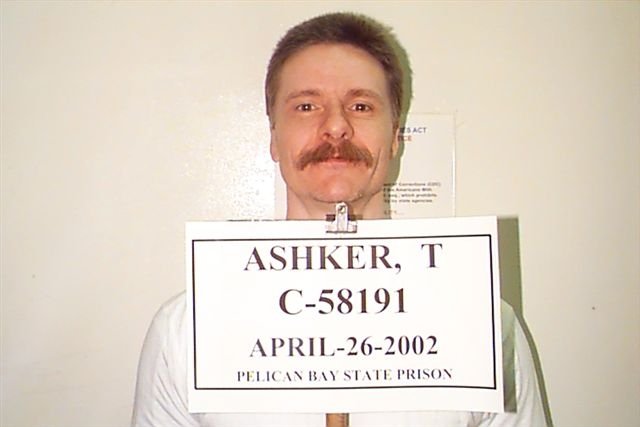

The lawsuit was initially filed in 2009 by two killers serving time in the security housing unit at Pelican Bay. By 2012, Todd Ashker and Danny Troxell were among 78 prisoners confined in Pelican Bay's isolation unit for more than 20 years, though Troxell has since been moved to another prison.

More than 500 had been in the unit for more than 10 years, though recent policy changes reduced that to 62 inmates isolated for a decade or longer as of late July.

The lawsuit contended that isolating inmates in 80-square-foot cells for all but about 90 minutes each day amounts to cruel and unusual punishment.

About half of the nearly 3,000 inmates held in such units are in solitary confinement. Inmates have no physical contact with visitors and are allowed only limited reading materials and communications with the outside world.

The settlement will limit how much time inmates can spend in isolation and create restrictive custody units for inmates who refuse to participate in rehabilitation programs or who keep breaking prison rules.

The units will also house those who might be in danger if they live with other inmates.

Lobel said the new units, by giving high-security inmates more personal contact and privileges, should be an example to other states to move away from isolation policies that he said have proved counterproductive in California.

Marie Levin, sister of 57-year-old reputed gang leader Ronnie Dewberry, read a statement from her brother, who goes by the name Sitawa Nantambu Jamaa, and other plaintiffs hailing the "monumental victory for prisoners and an important step toward our goal of ending solitary confinement in California and across the country."

With the pending policy changes, this will be the "first time Marie will be able to hold her brother, touch her brother, for 31 years," Lobel said on a conference call with Levin and other advocates.

Nichol Gomez, a spokesman for the union representing most prison guards, said it was disappointing that "the people that actually have to do the work" weren't involved in the negotiations. Gomez said she couldn't immediately comment further.

Beard said he will work to ease the unions' previously expressed concerns that guards could face additional danger. He said the settlement expands on recent changes that have reduced the number of segregated inmates statewide from 4,153 in January 2012 to 2,858 now.

Beard said the segregation system was adopted about 35 years ago after a series of slayings of inmates and guards and wasn't reconsidered until recently because California corrections officials were consumed with other crises, including severe crowding.

A Section on 09/02/2015