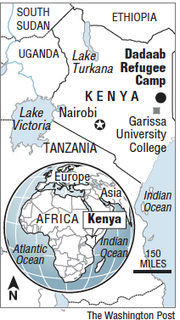

DADAAB, Kenya -- The Kenyan government is threatening to dismantle the world's largest refugee camp, setting off a panic among the 350,000 people who live there and the international aid organizations that care for them.

Kenyan officials say the camp is a national security threat, a constellation of tents and huts that are used by the Somali extremist group al-Shabab to plan attacks, like the one on Garissa University College that killed 148 people in early April.

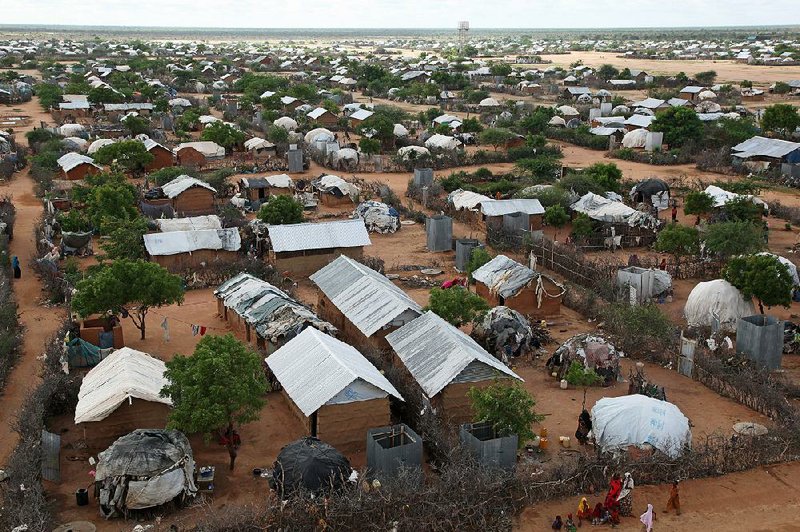

Nearly 25 years after it was constructed as a temporary solution for families fleeing Somalia's civil war, the Dadaab refugee camp is now a sprawling city. Dispelling its occupants would not only be a logistical nightmare, aid officials say, it also would be a humanitarian disaster.

Some experts doubt that Kenya will go ahead with the drastic step. But the announcement has created new concerns at a moment when the global number of refugees has surged to its highest level since World War II, leaving aid organizations strained.

More than 700 people died in late April when an overcrowded boat capsized in the Mediterranean Sea, a vivid sign of the growing number of African and Middle Eastern residents fleeing oppression, war and poverty.

Sulekho Dahir, 20, heard the news of Kenya's order on the radio, in her house made of sticks and a plastic tarp, a duplicate of thousands of others on the flat expanse of scrubland near the Kenya-Somalia border. The announcer read a statement from the vice president: "The way America changed after 9/11 is the way Kenya will change after Garissa."

Dahir was born in the camp. She was married there. A few years ago, she gave birth to her daughter there. Her "alien identification card" lists her nationality as Somali, but she has never been to Somalia.

The voice on the radio said she would have to leave in three months.

When the camp was built in 1991, it was just an agglomeration of white tents. There's now a sense of permanence, in its 52 schools and its 11 police stations, the thousands of cinder-block huts with tin roofs, and such establishments as the Yasir Driving School, the Amazing Grace Hotel and the Best Friends Electronics store. But mostly the permanence takes the form of people such as Dahir, who watch from afar as Somalia is buffeted by one crisis after the next.

Sending them back when al-Shabab still controls vast parts of the country "would be a disaster, a human tragedy and a humanitarian catastrophe," said Leonard Zulu, the acting director for the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, in Dadaab.

In North Africa, thousands of African refugees and asylum-seekers board shoddy boats to flee to Europe, many of them dying en route. But Dadaab appears to be a symbol of a different kind of refugee crisis -- an aging support system for those fleeing conflict and famine, in which resources are stretched thin as tension with host countries mounts.

The U.N. High Commissioner for Refugees' funding needs have grown by 130 percent since 2009, but its budget has increased by only 70 percent, according to a forthcoming report from the Washington-based Migration Policy Institute. Signs of the shortfall in aid are evident in Dadaab, where childhood malnutrition hovers around 10 percent.

Although the camp was constructed as a temporary refuge for people fleeing Somalia's civil war, that conflict never ended, instead evolving with the emergence of Islamist groups and eventually al-Shabab, which is linked to al-Qaida.

More refugees poured into Dadaab when Somalia faced a famine in 2011.

The number of resettlement slots for refugees in Europe and the United States is tiny compared with the demand. Only a small fraction of Dadaab's residents have been able to make that move.

The Somalia crisis has gone on for so long that many refugees don't have roots in any country. Somalia is a place that Dahir hears about on the radio and television: "Bombs going off, people getting murdered, no schools or hospitals," she said.

In the past month, al-Shabab militants have attacked a U.N. convoy, the higher-education ministry, a popular restaurant and hotel, and other targets.

Even Kenya -- or the Kenya outside of the camp -- is a distant land to Dahir, inaccessible with her alien identification card. So the idea that she would go somewhere else, in either direction from Dadaab, makes little sense to her.

"There's nowhere else," she said.

As Dadaab has grown, so have the security problems it poses. Al-Shabab militants have been able to slip into the camp, according to Kenyan officials, hiding weapons and recruiting young fighters. After Kenya sent troops into Somalia in 2011 to fight the extremists, there was a string of retaliatory bomb attacks on police trucks in the camp, and six foreign aid workers were kidnapped.

Kenyan officials offer a range of reasons why some of Dadaab's refugees support al-Shabab -- clan ties, pressure from militants, financial compensation. But evidence supporting those claims has never been made public.

After the 2013 attack on a Nairobi mall left 67 dead, Kenyan officials reiterated their belief that Dadaab was a safe haven for terrorists. Parliamentarians and Cabinet members, including the interior minister, asked for Dadaab to be closed. That didn't happen, and many believe the current plan will similarly fade away.

"It's a threat the government made to show they're doing something to combat the terrorism problem, but to carry out a shutdown would be quite difficult," said Mark Yarnell, a senior advocate for Refugees International, a Washington-based research organization.

Kenya is a signatory of the 1951 U.N. Refugee Convention, which forbids the involuntary return of refugees to a country where they face persecution. In 2006, Kenya passed its own law enshrining the rights of refugees, though critics say it has been poorly implemented.

Already, the Kenyan government appears to have backed away from the initial three-month timeline to close Dadaab. The foreign minister, Amina Mohamed, said the pace of repatriation "will depend on available resources."

Still, the United Nations and other aid organizations appear to be taking seriously the government's pledge to close Dadaab. The head of the U.N. High Commissioner for Refugees, Antonio Guterres, is to visit the camp soon. U.N. officials have been discussing the issue with the Kenyan government.

One potential problem is that dispersing the refugees, nearly half of whom are younger than 18, would create a plentiful pool of young men susceptible to al-Shabab recruitment or abduction.

"What will happen to all the youths not occupied in school and vocational activities?" asked Zulu, the U.N. High Commissioner for Refugees official.

Still, U.N. officials acknowledge the security concerns in Dadaab. The situation is so unpredictable that even Kenyan employees working for the United Nations are allowed to travel in the camp only with armed escorts during small windows of time each day.

"It's as if we've lost this part of the country," said Albert Kimathi, the deputy county commissioner in Dadaab. "For al-Shabab, this is a haven."

Many of the refugees in Dadaab say it's unfair to depict it as a sanctuary for terrorists. The people who live there are victims of al-Shabab, they say, not sympathizers.

Ahmed Mohammed Salem, who said he was accused of theft by al-Shabab, rolled up his jacket sleeve to reveal the stump of his right arm, which he said was cut off in 2012 in Mogadishu, the Somali capital.

"If I go back, they will kill me," he said. "This place is hard, but the situation is much worse over there."

SundayMonday on 05/03/2015