Correction: Cotton Plant is in Woodruff County. This story on Sister Rosetta Tharpe misstated the county.

The woman called the Godmother of Rock 'n' Roll would have turned 100 years old a couple of days ago.

Sister Rosetta Tharpe was born on March 20, 1915, in the Monroe County town of Cotton Plant. Raised on music in the "Holy Roller" tradition of the Church of God in Christ, she began singing and playing guitar when she was still so young she had to be placed atop a piano so the congregation could hear her.

The music she would go on to make in her lifetime, a hybrid of gospel and blues and a forerunner to rock 'n' roll, would have a profound impact on American culture. And, like so many great and familiar American stories of fame and artistry, hers would have ecstatic highs and depressing lows.

She sold millions of records through the 1930s and into the '50s, performed at the Cotton Club with Cab Calloway, toured incessantly and dressed in fine furs. More than 20,000 people packed Griffith Stadium in Washington to see her marry her third husband.

She gave Little Richard his first paying gig. Johnny Cash called her his favorite singer and mentioned her by name during his speech at his 1992 induction into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. (Inexplicably, Tharpe has yet to be enshrined there.)

Elvis Presley and Isaac Hayes were devoted fans. Jerry Lee Lewis said, "There's a woman that can sing some rock 'n' roll. She's ... shakin', man .... She jumps it. She's hitting that guitar, playing that guitar and she is singing ... whoooo ... Sister Rosetta Tharpe."

Fast forward to this century and it doesn't take much of a search to find her influence on artists like guitar-slinging frontwoman Britney Howard of the Alabama Shakes. Rhiannon Giddens of the Carolina

Chocolate Drops recorded Tharpe's "Up Above My Head" on her solo album, Tomorrow Is My Turn. And Robert Plant and Alison Krauss paid tribute to the Arkansas native with the sweet "Sister Rosetta Goes Before Us," on the album Raising Sand.

On songs like "Rock Me," "Shout, Sister, Shout," "This Train" and "Strange Things Happening Every Day," Tharpe brought Delta blues, swing, jazz and gospel together, often to the chagrin of one group or another -- too churchy for the secular crowd, too secular and showy for some of the church crowd. Still, she had a particular genius for, as biographer Gayle Wald aptly noted, "mixing piety with pageantry," and had no problem performing her gospel music in nightclubs and other worldly venues.

"What makes her so cool is that she was doing something that no one was doing back then and still no one is doing today." That's Stephen Koch, the Little Rock-based writer, radio host and expert on all things related to Arkansas music. He is spending the month saluting Tharpe on his weekly KUAR program Arkansongs.

"She was playing this incredible, electric rock 'n' roll before there was even a name for the genre," says Koch, author of the biography Louis Jordan: Son of Arkansas, Father of R&B. (Like Tharpe, Jordan was a Monroe County native, having been raised in Brinkley). "Listen to the stuff that [Led Zeppelin guitarist] Jimmy Page was doing years later and to think that a black woman was doing that in a gospel setting is amazing."

Koch is organizing a May 8 tribute at Little Rock's Old State House Museum in conjunction with Second Friday Art Night that will feature film clips, music and celebration of Tharpe and her legacy.

He's got a Tharpe musical, Can't Sit Down, in the works (he also wrote Jump, a musical based on Jordan's life), with Little Rock actress and his former sister-in-law, Ganelle Holman, in the title role.

"I admire her bravery and how courageous she was in taking her message from church and into the secular world," Holman, founder of the No Cotton Theater Company, says of Tharpe. "She might not have been the very first, but she was a pioneer."

Amy Garland Angel is a Little Rock singer-songwriter and host of "Backroads," 5-7 p.m. Fridays on KABF-FM, where she's been known to play a Sister Rosetta song or two.

"I've loved her for a long time," Garland Angel says. She became a fan after her social work professor at the University of Arkansas at Little Rock, the late Nancy Harm, passed along one of Tharpe's albums. "I realized the majority of my influences -- Maria Muldaur, Bonnie Raitt, Rory Block, Marcia Ball -- had all credited her as an influence. People I'd been listening to all my life, she influenced them and they passed it down. And I realized that she was a rock star before there were rock stars."

...

By the time she was 10 years old, Tharpe and her mother, Church of God in Christ evangelist Katie Bell, left Cotton Plant for Chicago. The pair hit the gospel circuit, performing and evangelizing. Tharpe's father, Willis Atkins, a cotton picker, was left behind and had nothing else to do with his daughter's life, though she would become close later in her life with his children from a subsequent marriage.

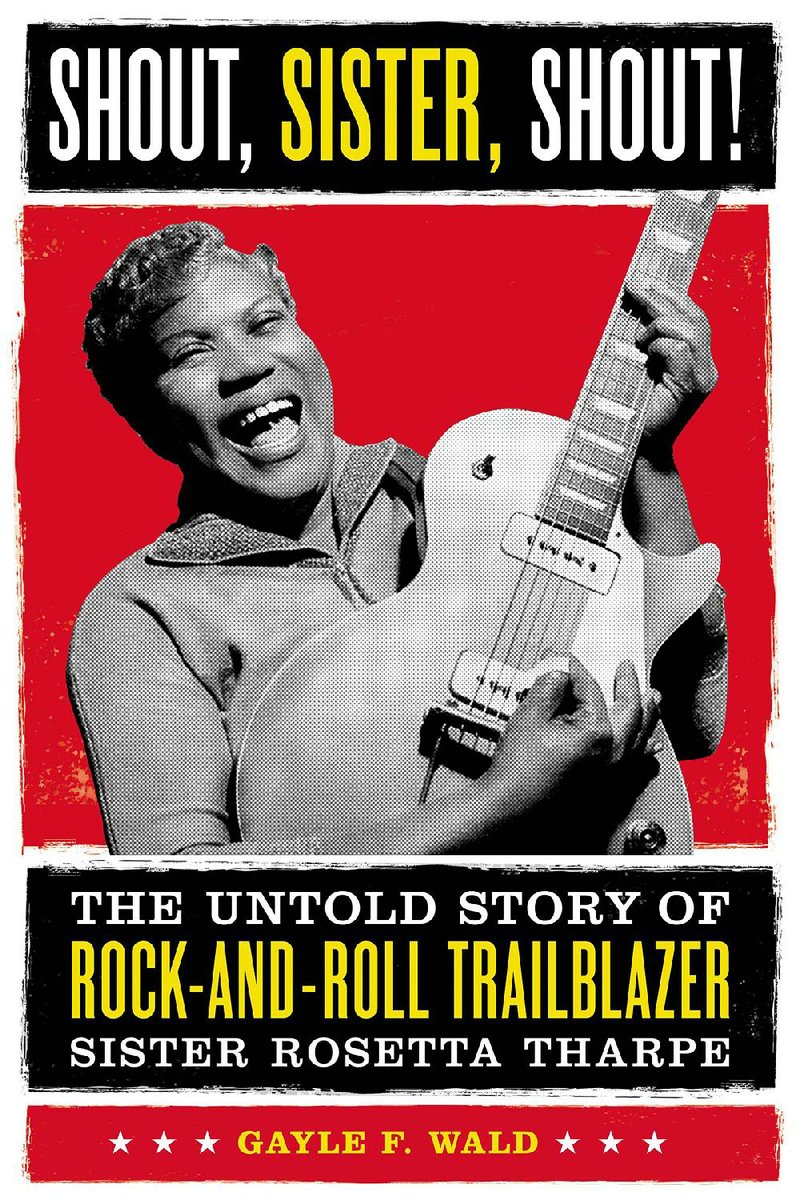

Katie Bell was strict, writes Wald in the quintessential biography Shout, Sister, Shout: The Untold Story of Rock-And-Roll Trailblazer Sister Rosetta Tharpe, shielding Rosetta from Chicago's thriving secular music scene and keeping her focused on the sanctified path.

Still, Rosetta was playful and outgoing, finding happiness in the attention her playing and singing brought (and the money she and her mother earned from the collection plate).

She met her first husband, itinerant preacher Tommy Tharpe, while on the road with Katie Bell. They married on Nov. 17, 1934, and later relocated to Miami, attracting a strong following in the COGIC scene.

By 1938, though, neither her husband nor the Pentecostals could hold her in south Florida, and Tharpe got a gig at New York's infamous Cotton Club, the nightspot that featured black performers like the mighty Cab Calloway and the Nicholas Brothers, playing for all-white audiences who were smoking and drinking and, from the outset, Wald writes, "were thrilled by Rosetta's unusual sound and style." She was also being compared to the great blues singer Bessie Smith, who died in a car accident the year before.

Of course, some of the sanctified weren't pleased.

"She had this troubled relationship with the church," Koch says. Her gospel songs had a worldly element.

"'This Train' is a linchpin-type song," Koch says. "In terms of lyrics, it was a gospel number, but it was also something that was beyond biblical."

...

For Tharpe, 1938 was a big year. Not only was she playing the Cotton Club, but she signed a contract with Decca Records, home to Louis Armstrong, Count Basie, Chick Webb and Ella Fitzgerald. The label had recently dropped gospel singer Mahalia Jackson, to whose career Tharpe's would often be compared.

"With her bell-like voice, winning smile and Cotton Club notoriety, Rosetta had the combination of the musical goods and showbiz flair that Mahalia had lacked," Wald writes.

On Dec. 3, 1938, Tharpe was included in the concert From Spirituals to Swing, a sold-out performance at New York's Carnegie Hall that included bluesmen Jimmy Rushing and Joe Turner, Albert Ammons, jazzman Sidney Bechet and Count Basie, and was produced by John Hammond. Wald calls it "one of the most historically significant musical events of the first half of the 20th century."

She would record with Lucky Millinder's Band, including the decidedly secular romp "I Want a Tall Skinny Papa" and a big-band version of "Rock Me." As World War II commenced, she even recorded V-Discs for troops overseas.

It's hard to overstate how much of an influence her guitar playing had, and what a novelty it was for a woman, a black woman singing gospel, to play the way she did. One chapter of Wald's book is even called "She Made That Guitar Talk."

"She had the coolest riffs," Garland Angel says. "She would bend her notes like they do now, but it was rare for a woman to do that back then. She was always in the groove and in the pocket. She was the quintessential showman."

...

By the mid-1940s she'd recommitted solely to gospel, though she still played theaters and clubs and recorded with boogie-woogie pianist Sammy Price, including the magnificent "Strange Things Happening Everyday," a solid cinder block in the foundation of what would become rock 'n' roll. (Lewis sang it when he auditioned for Sun Studios producer Sam Phillips.)

Tharpe teamed with her pal Madame Marie Knight and the pair recorded and toured through the late '40s. She stayed on the road into the '50s, even buying a bus and hiring a white driver, who had the added benefit of being able to order food for the hungry musicians at segregated restaurants in the South.

Her popularity waned by the '60s, her Griffith Field marriage to Russell Morrison in front of all those fans a fading memory, but Tharpe continued to tour and record. Like many black artists from the U.S., she found kinder audiences (and improved traveling conditions without Jim Crow laws and rampant segregation) in Europe, where she influenced countless acts that would soon be part of the British Invasion.

Tharpe was diabetic and in the early '70s one leg was amputated, curbing her playful spirit and ebullience, though she continued to perform because money was tight.

She was scheduled to record an album in October 1973 for Savoy Records, but the date was pushed back. Sister Rosetta Tharpe died Oct. 9, 1973, of a blood clot on the brain. The Godmother of Rock 'n' Roll was buried in an unmarked grave in Philadelphia's Northwood Cemetery, with a rumor circulating that her husband sold off the white Gibson SG guitar that was supposed to be buried with her.

Though she died with her headiest days of fame behind her, her musical legacy is undeniable.

"A lot of people have forgotten who she is," Koch says, "but there should be a nationwide celebration of Sister Rosetta Tharpe."

Style on 03/22/2015