WASHINGTON -- Two Guantanamo Bay detainees are using President Barack Obama's words to argue that the U.S. war in Afghanistan is over and that they should be set free.

The court cases from detainees captured in Afghanistan ask federal judges to consider at what point a conflict is over and whether Obama, in a statement in December, crossed that line by saying the American "combat mission in Afghanistan is ending."

The questions are important because the Supreme Court has said the government may hold prisoners captured during a war only for as long as the conflict in that country continues.

"The lawyers for the detainees are asking the right questions," said Stephen Vladeck, a national security law professor at American University. "And what's really interesting is that the government can't quite seem to figure out its answer."

The Justice Department is opposing the detainee challenges, arguing that the conflict in Afghanistan has not concluded and that the president didn't say all fighting had ended.

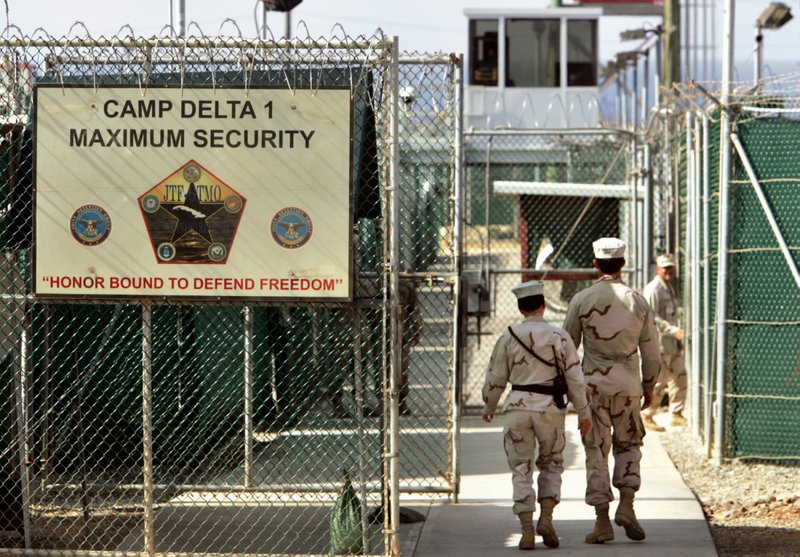

The court challenges are the latest in the years-long legal wrangling tied to Guantanamo, whose status as a prison for terrorism suspects has defied resolution. Obama promised to close the prison at the U.S. naval base in Cuba, and the government has transferred out more than half of the detainees who were there when he took office in 2009.

At its peak, in June 2003, Guantanamo held nearly 700 prisoners. More than 500 were released under President George W. Bush. Obama had promised to close the prison within a year of taking office, but Congress stopped him by imposing restrictions on transfers.

In the past decade, detainees have challenged the military tribunal process used to prosecute them, their treatment behind bars and efforts to force-feed them, among other issues.

The latest arguments have played out in recent months in federal court in Washington. No judge has ruled in the cases, although legal experts say they expect an uphill battle for the detainees, given the deference courts generally afford to the government on matters of national security.

One of the petitions was brought by Faez Mohammed Ahmed al-Kandari, a Kuwaiti who was shipped to Guantanamo after his 2001 capture after the battle of Tora Bora. Another challenge came from Muktar Yahya Najee al-Warafi, a Yemeni who a judge has determined aided Taliban forces.

The two men, both held without charges, argue that an end to the fighting in Afghanistan means their detentions are now unlawful under the 2001 Authorization for Use of Military Force. That law provided the legal justification for the imprisonment of foreign fighters captured on overseas battlefields. The Supreme Court stressed in a 2004 case, Hamdi v. Rumsfeld, that such detention is legal only as long as "active hostilities" continue.

Defense lawyers say Obama unequivocally signaled an end to the military conflict Dec. 28 when he declared that "our combat mission in Afghanistan is ending, and the longest war in American history is coming to a responsible conclusion."

In a court filing, lawyers for al-Kandari wrote that "there is no longer a battlefield in Afghanistan in which the United States is sustaining active combat operations. Accordingly, there is no longer a basis under the international laws of war to detain" their client.

But the Justice Department said "active hostilities" clearly persist against the Taliban and al-Qaida and that Obama never suggested that all military and counterterrorism operations would be coming to an end.

The government said Obama noted at the time that the U.S. would maintain a limited military presence. About 9,800 troops remain there, advising and assisting the Afghans and conducting some counterterrorism missions. In addition, the Justice Department has said, questions about the status of war are for Congress and the president to decide, not the courts.

"Simply put, the president's statements signify a transition in United States military operations, not a cessation," government lawyers wrote in April in a reply in al-Warafi's case.

"Presidents say things," said Eugene Fidell, a Guantanamo expert who teaches military justice at Yale Law School. As one example, he recalled President George W. Bush's celebratory Iraq War speech in 2003, delivered from the deck of an aircraft carrier under a "Mission Accomplished" banner.

"Well, the mission wasn't accomplished," Fidell said. "Perhaps some presidential statements of fact have an aspirational flavor."

A Section on 06/18/2015