For Ruthie Chaney it was a rhythmic "click, click, click, click" from a nearby clock. For Stacy Cockrell, it was "wah, wah, wah," which, thanks to stellar lip-reading skills, she was able to interpret as her mother's "I love you."

The Internet provides hours of cochlear implant activation footage, and people's reactions to being able to hear for the first time -- or for the first time in a long while -- are as disturbing as they are miraculous.

"Crying is not uncommon," says otolaryngologist Dr. John Dornhoffer, who has placed implants in more than 1,000 patients at UAMS Medical Center and Arkansas Children's Hospital. And he's talking about tears of horror and frustration, not tears of joy.

On YouTube, a man named Chris mistakes his female audiologist's voice for a piano, while his own voice sounds like "a perfect Dr. Who robot."

In another clip: "It's so weird," Jodi Goodenough says tearfully. "I don't like it."

It took Levi Sims, a 21-year-old Arkansas Tech University student, three years to appreciate his implants. University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences professor and audiologist Sam Atcherson, 39, didn't feel confident using the phone for two years. Cockrell, 52, thought some people sounded like "Darth Vader" and found the follow-up home therapy exhausting after a day of handling data for Blue Cross Blue Shield. If it weren't for a friend who spent nearly every evening for three months working with her, she might have given up the implants.

But Sims, Atcherson, Chaney and Cockrell all agree -- they wouldn't trade the experience of being able to hear, even in a way that most people find "abnormal," for anything.

HOW IT WORKS

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved the threading of tiny electrodes into the inner ear's whorled cochlea in 1985. According to the FDA, by December 2012 there were 324,200 cochlear implant users worldwide and 96,000 in the United States.

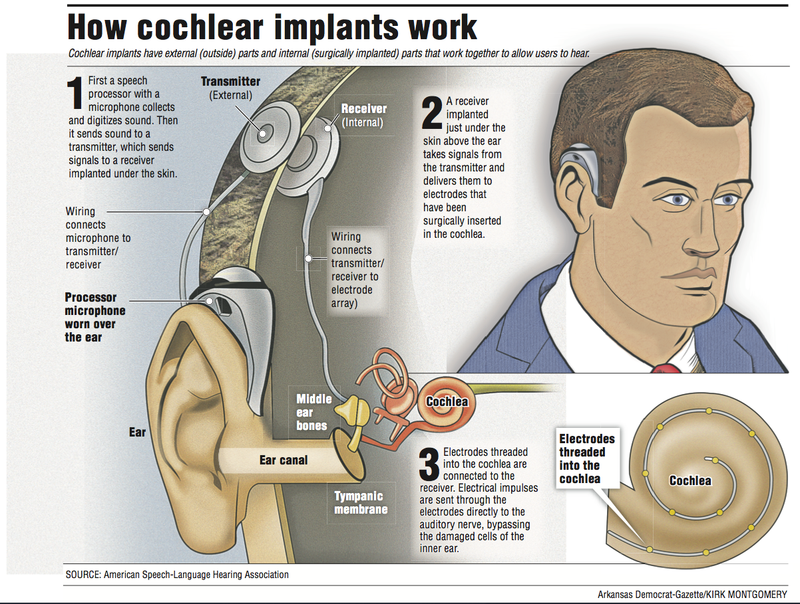

It works like this: a bone behind the ear is removed, and a bundle of electrodes is inserted into the inner ear's cochlea, a fluid-filled cavity that houses the receptor organ for hearing (the corti). The electrodes are attached to a small receiver, which is fixed to the skull. Then the surgeon replaces the bone and closes the skin.

A removable "processor" curls around the external ear, resembling a hearing aid. It contains a microphone to collect sound and a tiny computer that converts the sound to digital code. That code is sent to the receiver, where it becomes electrical impulses that pulse through the electrodes directly to the auditory nerve, bypassing damaged, tiny, hair cells lining the inner ear.

With cochlear implants, deaf and hard-of-hearing people can recognize and interpret sound, but according to Dornhoffer, they "hear" differently from nonimplanted people. That's because when hair cells are healthy, they modulate and shape sound in a way that researchers are unable to understand and replicate.

"You have to retrain your brain to learn what those sounds are," Dornhoffer says.

The first time Sims heard a sink running through his implants, he

thought it sounded like "a loud machine." But within a few weeks, his brain began interpreting the sound as an "ordinary" faucet, and it began to sound the way he remembered, from before he lost his hearing and later, with hearing aids.

Stimulating the cochlea in different places results in different tones. The first cochlear implants only had one electrode, which made everything sound monotone and mechanical. Now there are multiple-electrode implants that offer more tone sensitivity.

"No one likes it at first. You turn it on, they say it sounds like a bunch of beeps ... then, between three and six months, they say, 'Maybe this is going to work.' ... At six months they start performing pretty well, and at nine months, they're curious about a second one," Dornhoffer says.

A TOOL, NOT A CURE

Chaney, a 20-year-old University of Central Arkansas student, was 7 when she received her first implant. Every time she gets her processor "remapped," people "sound like Mickey Mouse" for a couple of days, she says.

"Mapping" is when an audiologist tweaks the computer programs in the processor. Programs are designed for assorted listening situations -- one-on-one conversation, noisy environments, talking on the telephone or listening to music. Some processors can hold up to five programs, which an implant-user switches among using a tiny dial on the processor, or a remote control.

Cochlear implants can't help every deaf or profoundly hard-of-hearing person. A candidate must have a functioning auditory nerve and an ear with basic structural integrity. Candidates also must be willing to do the follow-up therapy and, generally, there are better outcomes if a candidate is pre-lingual (under age 3) or already oral (lost hearing after acquiring language).

Dornhoffer no longer gives implants to pre-lingually deafened adults because of the low chance of achieving oral and aural communication.

"When cochlear implants first came out, we implanted everybody. Then there were a lot of people who weren't happy campers. They never got it. They threw them out," he says.

Atcherson says early technology contributed to the problem. "The surgical technique was very crude. People would have taste disturbances, facial twitching ... so there's this lingering anger, I think."

Even now, his facial muscles twitch if he turns the volume too high on his implant.

"You don't want so much current going in that you stimulate other stuff you shouldn't be stimulating," he says.

The facial nerve lies next to the auditory nerve, and facial paralysis can be an unfortunate side effect. But according to Dornhoffer, in two decades of doing implants, he has never injured a facial nerve.

POLARIZING PROCEDURE

Dornhoffer has been called a "child abuser" for performing cochlear implants, and Cockrell had a deaf friend break ties with her after she got her first implant at age 46. To some, including 56-year-old Little Rock artist Robert Walker, deafness is a "natural state" and a culture, not a disability.

"As a whole, we don't see it as something to be 'fixed,'" he types on his iPad. "It's a means of personal identification in terms of validating our existence [with language and our cultural mores]."

He doesn't want "a machine" in his head, and he thinks doctors are too quick to offer implants as a solution to hearing parents without informing them of other communication and education options.

"Slapping an implant on a child and not allowing exposure to other deaf children who use ASL [American Sign Language] is not being given a chance to gain a sense of connection with his peers," he types. "It's not something you can get back."

He started and finished his education at schools for the deaf, including studying graphic design at Gallaudet University, a bilingual (American Sign Language and English) college in Washington. He regrets that his middle and high school years were spent at a mainstream school.

Walker uses sign language, pantomime and his iPad to communicate with his clients and other hearing people. "I can pretty much move back and forth between deaf and hearing worlds ... though I am way more comfortable in deaf world," he types.

Dornhoffer has genetic, progressive hearing loss and will soon receive a cochlear implant. "One way to embrace adversity is to turn it into something special ... and that's great, but [deafness is] a disability," he says. "The world doesn't work that way. The world communicates by phone."

But Walker isn't interested in communicating by phone. "More and more schools for the Deaf are being shut down. More and more Deaf children are being taken out of [the] Deaf community and they have no role model from Deaf adults ... [deaf people] are being psychologically displaced," he types.

Chaney (the UCA student) is among a small group of implant-users who also sign. Even while communicating orally, she punctuates her thoughts with casual, informal (one hand instead of two) signs, in the same way that all multilingual people sprinkle their first language into conversations in newer languages.

She admits having felt out of place as the only hard-of-hearing student among the 27 in her Hattieville graduating class, but she loves college because "it's such a diverse place." She has hearing and hearing-impaired friends and hopes to be an audiologist.

"I wanted to hear my entire life, and I knew I was missing out on a lot of things socially," she says. "I don't think I would have made it this far into college without the implant."

NO MORE LIP READING

When Cockrell finally decided she wanted implants, after a lifetime of lip reading and 17 years of speech therapy, she worried that she wouldn't be a candidate. With 10 percent hearing in one ear and 5 percent in the other, she thought she might hear too well with hearing aids to qualify for an implant.

During her examination, she turned up her hearing aids and strained for the sounds and snippets of conversation piped into the sound booth.

When she emerged from the booth, the audiologist had surprising news. Cockrell had misidentified every sound.

Two months after her first implant was activated, Cockrell took the test again and scored 68 percent. Eight months in, her score had jumped to 92 percent.

COST CONTROL

Some people want cochlear implants and are good candidates, but they never get one. That's because the devices and procedure are prohibitively expensive, costing between $40,000 to $65,000.

Private insurance pays to varying degrees. Dornhoffer says, "Medicare covers 80 percent of it, and you have to get a supplement to cover the rest." This is significant, because he has provided implants to patients in their 80s and 90s.

Medicaid will cover the procedure for patients under 21, but in Arkansas, it doesn't cover cochlear implants for adults. And it doesn't pay for processor updates unless the processor is broken, says Kristi Bell, whose son Brett, 12, got an implant at 7.

"A lot of people don't do them in private practice," Dornhoffer says. "You have to have a pretty big volume in order to get decreased costs from the supplier."

His cochlear implant program has been halted due to cost more than once, he says. "So I've talked to the implant companies, tried to get prices reduced. The bottom line is, we're not making money, but we're not bleeding money. In the past, we've lost money."

FINALLY HEARING

"After the implant, we saw a big difference in Brett's frustration level," Bell says. He threw fewer temper tantrums and interacted more with his family and teachers.

Cockrell remembers the first time she overheard the phone conversation of a co-worker in a neighboring cubicle and how she ran over and squealed, "You were on the phone with your son, and y'all were talking about getting tickets to the Travelers game!"

"What are you doing listening to my conversations?" her friend teased, before standing up and throwing her arms around Cockrell.

When Atcherson, who plays guitar and piano, received his first implant at 25, he was thrilled to be able to hear the vocals in songs again. With his hearing aids, he could only hear the instrumentals.

Sims labels "hearing" his favorite sense.

"If it wasn't for the implant, I honestly don't know where I would be in life. Not sure if I would be in college," he says.

Sometimes Chaney's friends call her "cyborg." She shrugs it off.

"I respect the deaf culture for trying to keep their borders, but the thing I like about cochlear implants, you're in those borders but you're also outside. You're integrating those borders into one," she says.

ActiveStyle on 07/20/2015