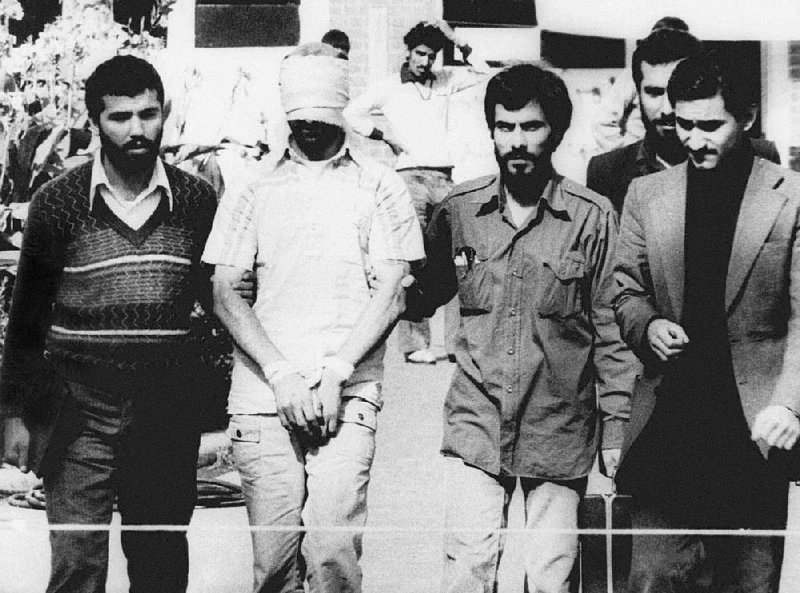

WASHINGTON -- After spending 444 days in captivity and more than 30 years seeking restitution, the Americans taken hostage at the U.S. Embassy in Tehran in 1979 have won compensation.

Buried in the huge spending bill signed into law late last week are provisions that would give each of the 53 hostages or their estates up to $4.4 million. Victims of other state-sponsored terrorist attacks such as the 1998 U.S. Embassy bombings in East Africa also would be eligible for benefits under the law.

"I had to pull over to the side of the road, and I basically cried," said Rodney Sickmann, who was a Marine sergeant working as a security guard at the embassy in Tehran when he was seized along with the other Americans by an angry mob that overran the compound on Nov. 4, 1979. "It has been 36 years, one month, 14 days, obviously, until President [Barack] Obama signed the actual bill, until Iran was held accountable," he said.

The law now stands to bring closure to a saga that riveted the nation and ruptured the United States' ties with Iran.

The hostages were barred from taking legal action against Iran under the 1981 Algiers Accords, brokered by Algerian diplomats, that led to their release. Fifty-two hostages were released on Jan. 20, 1981; a 53rd hostage had been released earlier because of illness.

U.S. courts, the State Department and presidents all opposed attempts to sue, citing the deal reached in Algiers. So lawyers turned to Congress for help, but even those efforts failed time and again.

But this year, vindication came in a decision that forced the Paris-based bank BNP Paribas to pay a $9 billion penalty for violating sanctions against Iran, Sudan and Cuba. Some of that money was made available for victims of state-sponsored terrorism.

Congress also was motivated by many members' anger over the Iran nuclear accord, which was hailed this year as a herald of warmer relations with the Islamic republic.

Some of the hostages were subject to physical and psychological torture during their long ordeal, and many regarded the thaw as frustrating and premature.

Like most of the hostages, Sickmann learned of the imminent legislation in a conference call with their main lawyer, Thomas Lankford, on Dec. 16.

"It became clear that we were sort of inextricably linked to the nuclear negotiations," Lankford said in an interview. "Those negotiations resulted in an understanding that an inevitable next step in securing a relationship was to address the reason for the rupture, which was our kidnapping and torture."

"As valuable as stopping the spread of nuclear arms is," he added, "it's equally important to establish the precedent that in one way, shape, form or another, a state sponsor of terrorism will not be permitted to walk away."

It is not clear, however, whether all the former hostages or their families will receive full payments. In large measure that is because the $4.4 million maximum authorized by Congress depends on the outcome of efforts to collect on judgments won in earlier court rulings involving victims of terrorist attacks, as well as on the number of victims who file claims.

The law authorizes payments of up to $10,000 per day of captivity for each of the 53 hostages, 37 of whom are still alive. Among the hostages were two Arkansans, Marine Sgt. Steven Kirtley and State Department employee Robert Blucker, who died in 2003. Efforts by the Arkansas Democrat-Gazette to reach Kirtley for comment were not returned by Thursday evening.

Spouses and children are authorized to receive a lump payment of as much as $600,000.

Of the $9 billion penalty paid by BNP Paribas, about $1 billion will be put into a compensation fund for victims of terrorism, with more money and assets potentially added as a result of continuing litigation. An additional $2.8 billion will aid victims of the Sept. 11, 2001, attacks and their family members.

Initial payments are to be disbursed within one year, according to a formula that will be overseen by a special master appointed by the Justice Department and that imposes limits on payments to victims who have won judgments in excess of $20 million. The initial payments are expected to fall well short of the maximum.

Argo factor

Several of the surviving hostages and their families said that reparations were long overdue and would serve as an important symbol.

Some said they thought the push to reconsider their claims came after the Iran nuclear deal in July, which angered many members of Congress, and the 2012 Ben Affleck film Argo, which focused on six people who managed to escape from the besieged embassy and take refuge in the home of the Canadian ambassador, Ken Taylor.

"I think Argo, followed by the Iran nuclear accord, was very instrumental," said Joe Hall, 66, who was an Army chief warrant officer and operations coordinator for the U.S. defense attache at the embassy.

When Lankford told Hall and other hostages in a conference call that the compensation had been enacted, Hall said, "I had the phone on mute and sat in shock for a few minutes. It was an emotional moment, by myself in the woods."

Some of the hostages also said the compensation award would serve as a reminder of the perils still faced by U.S. diplomatic personnel working in dangerous locations overseas, such as the diplomatic compound in Benghazi, Libya, where Ambassador J. Christopher Stevens and three other Americans died in 2012.

For years, the hostages pushed for relief from Congress.

"Time and time again, we thought we'd get a bill," said David Roeder, a retired Air Force colonel who was an attache at the embassy in Tehran when he was taken hostage. "We were pushing toward the goal line, and our portion would get stripped out."

Roeder called the experience "the epitome of the roller-coaster ride."

He added, "We were sent into harm's way by our government, and then nobody seemed to want to do anything about it."

Over the years, the former hostages had numerous champions in Congress. In recent years, some of their strongest advocates included the Senate Democratic leader, Harry Reid of Nevada, and Sen. Johnny Isakson, R-Ga., each of whom had former hostages or relatives of hostages living in their home states.

Isakson -- chairman of the Senate Veterans Affairs Committee who counts three former hostages, including Hall, among his constituents -- introduced the compensation legislation for the hostages.

"The Iran hostages sacrificed mightily for our country, and I'm delighted that these brave men and women and their families are finally getting some semblance of justice and closure for what they went through," Isakson said in a statement.

In a statement, Reid said that the action by Congress was long overdue.

"These Americans, held hostage for 444 days in 1979, deserved to finally be compensated for the horrors that they and their families have survived," he said.

Sickmann, the Marine sergeant who was a hostage, said he would have preferred that Iran pay compensation directly, as Libya did for victims of the bombing of Pan Am Flight 103 over Lockerbie, Scotland, but that he did not expect an apology from Iran.

"I don't believe that they will ever, ever apologize," he said. "They don't believe that they did anything wrong."

Lankford, the attorney, said the source of the money didn't matter.

"Iran is not paying the money, but it's as close as you can get," he said, adding that the payment legislation was "gratifying after a long, long time."

Some former hostages and their family members had expressed frustration at the Justice and State Departments for blocking efforts over the years to get compensation. In a sense, the spending bill represents Congress' taking control of the BNP Paribas money back from the Justice Department.

Some hostages did not want to discuss the legislation. "It's enough," said Barry Rosen, who was a press attache at the embassy. "We've gone through enough."

Deb Firestone, whose father, Bruce German, left his wife and three children a year after his release, said her mother did not expect to see a settlement in her lifetime.

Firestone expressed relief at an overdue recognition of the lifelong grief the hostage crisis wrought.

"I'm glad the government has finally realized the hostages deserve something," she said.

Information for this article was contributed by David M. Herszenhorn of The New York Times and by Carol Morello and Frances Stead Sellers of The Washington Post.

A Section on 12/25/2015