LOS ANGELES -- It's almost as if the dozens of exquisitely detailed, often perfectly intact bronze sculptures on display at the J. Paul Getty Museum disappeared into an ancient witness-protection program -- and decided to stay there for thousands of years.

"Power and Pathos: Bronze Sculpture of the Hellenistic World," brings together more than 50 bronzes from the Hellenistic period that extended from about 323 to 31 B.C.

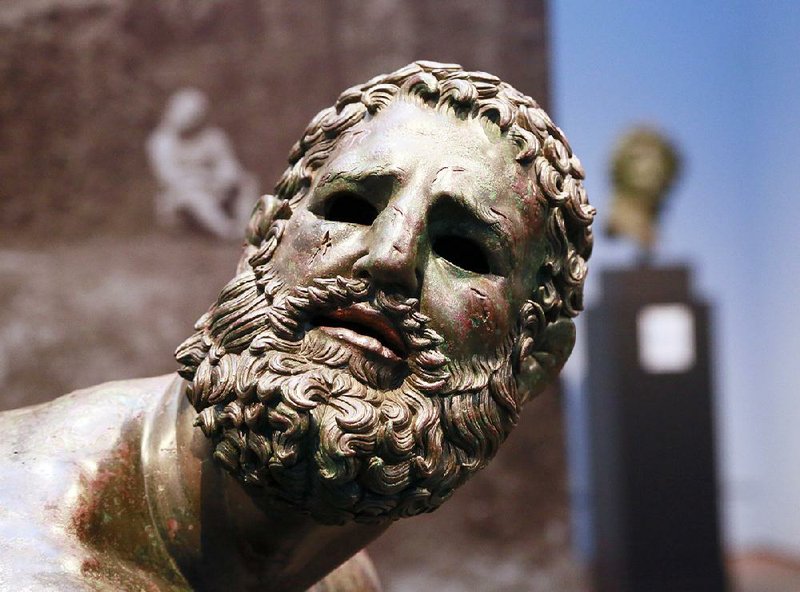

Many of them, like the life-size figure of an exhausted boxer, his hands still bandaged from a match, brow cut and bruised, are stunning in their detail. So is The Medici Riccardi Horse, a horse's head complete with flaring nostrils and a detailed mane.

Perhaps even more stunning, however, is the fact that any of these things survived.

Thousands of such beautifully detailed bronzes were created during the Hellenistic Age. Larger works were assembled piece-by-piece and welded together by artisans working in almost assembly line fashion and displayed in both public places and the homes of the well-to-do.

But most, say the exhibition's co-curators, Kenneth Lapatin and Jens Daehner, were eventually melted down and turned into something else, like coins.

"We know Lysippos made 1,500 bronzes in his lifetime, but not one survives," Lapatin said of the artist said to be Alexander the Great's favorite sculptor. "They've all been melted down."

The nearly 60 works that will be on display at the Getty Museum until Nov. 1 are believed to represent the largest such collection ever assembled. They have been contributed by 32 lenders from 14 countries on four continents.

"Many of these are national treasures," museum Director Timothy Potts said. "They are the greatest works of ancient art that these nations possess. So it's been an extraordinary act of generosity for them to be lent to us."

Many are completely intact, so much so that several still have their eyes, made of tin and glass.

"It's only through shipwrecks, through being buried in the foundations of buildings, being buried by a volcano at Pompeii or landslides that most of these pieces have survived," Lapatin said.

Herm of Dionysos, for example, was believed to have been commissioned by a wealthy Roman homeowner. The detailed work of a bearded man with hat and animated eyes was found in a shipwreck off the coast of Tunisia in 1907.

The sculpture of an athlete raising an arm in victory was uncovered in the Adriatic Sea by Italian fishermen in the 1960s.

The Pompeii Apollo was discovered in 1977 in the dining room of a house in Pompeii that had been buried by the volcanic eruption of Mount Vesuvius in A.D. 79.

It is believed to have been used, in a very ungodlike fashion, to hold the room's lights. That's something that inspired Lapatin to refer to it as the equivalent of a modern-day lawn jockey.

The exhibition was organized by the J. Paul Getty Museum, the Fondazione Palazzo Strozzi in Florence, Italy, and the National Gallery of Art in Washington. After it leaves the Getty, the exhibition will go on display Dec. 6 at the National Gallery of Art.

Information: getty.edu/museum

Travel on 08/30/2015