BILLINGS, Mont. -- Federal and state regulators underestimated the potential for a toxic blowout from a Colorado mine, despite warnings more than a year earlier that a large-volume spill of wastewater was possible, an internal government investigation released Wednesday found.

The regulators wrongly concluded that there was little or no pressure from the millions of gallons of water trapped inside the inactive Gold King mine, the federal Environmental Protection Agency concluded in its probe. It was unclear when that determination was made.

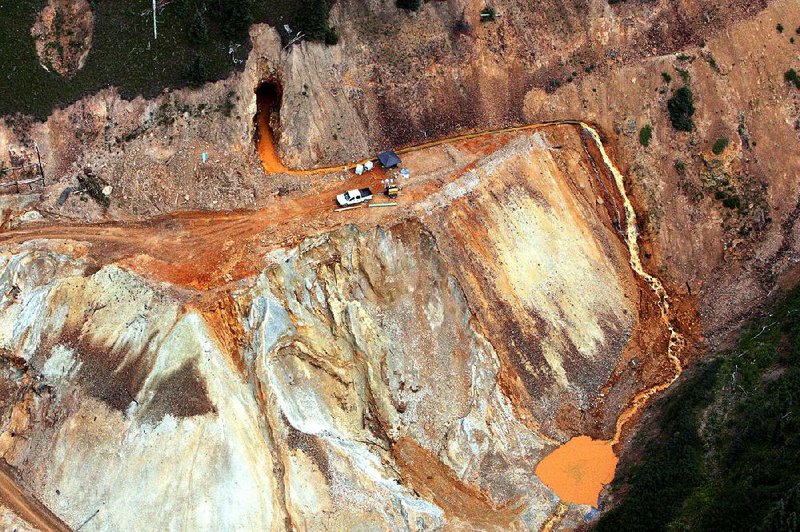

The spill occurred Aug. 5 when a government cleanup crew doing excavation work triggered the release of an estimated 3 million gallons of sludge that fouled hundreds of miles of rivers in Colorado, New Mexico and Utah.

The torrent of toxic water released from the mine also shut down some public drinking water and irrigation systems.

"There was in fact high enough water pressure to cause the blowout," EPA Deputy Administrator Stan Meiburg said in a conference call after the release of documents summarizing the investigation. He said the error was likely the most significant factor behind the spill.

The EPA previously offered only partial information on events leading up to the spill.

The investigation also revealed that regulators could have drilled into the mine to get a better gauge of how much pressure had built up.

While drilling would have been expensive and technically challenging, "this procedure may have been able to discover the pressurized conditions that turned out to cause the blowout," the documents say.

However, Meiburg said there was "no evidence to suggest this technique would be necessary," and other factors indicated there was little pressure inside the mine. Those included the lack of any seepage of water above the mine opening, which would have been a sign of pressure.

Based on other records, The Associated Press reported Saturday that EPA managers knew that a large spill was a possibility as early as June 2014, yet had drafted only a cursory plan for responding to a spill.

The EPA's internal investigation concluded that the spill was likely inevitable, despite the earlier warnings and the potential that drilling would have detected the built-up pressure in the mine.

EPA assistant administrator Mathy Stanislaus said it was unknown whether the drilling could have been done. He also said teams on the ground before the spill had seen draining water from the site, another indication that pressure buildup was not likely.

The documents said state officials from the Colorado Department of Natural Resources had supported the work done by the EPA team and were present on the day of the spill. Agency spokesman Todd Hartman said state officials were reviewing the EPA's conclusions and had no immediate response.

Elected officials have been critical of the EPA's handling of the spill and the slow pace with which the agency has released documents related to it. Among the unanswered questions is why it took the agency nearly a day to inform downstream communities that rely on the rivers for drinking water.

EPA officials acknowledged Wednesday that more efforts should have been made to notify downstream communities.

The metals-filled water flowed into a tributary of the Animas and San Juan rivers, turning them a yellow-orange and tainting them with lead, arsenic, thallium and other heavy metals that can cause health problems and harm aquatic life.

The toxic plume traveled roughly 300 miles through Colorado, New Mexico and Utah, to Lake Powell on the Arizona-Utah border.

EPA water testing has shown contamination levels returning to pre-spill levels, though experts warn some of the contaminants likely sunk and mixed with bottom sediments and could someday be stirred back up.

Toxic water continues to flow out of the mine. Since the spill, the EPA has built a series of ponds so that contaminated sediments can settle out before the water enters a nearby creek.

The agency said more needs to be done and the potential remains for another blowout.

Separate investigations into the spill are being conducted by the EPA's inspector general's office and the U.S. Department of Interior.

A Section on 08/27/2015