We are clearly nowhere near Halloween; days are getting longer and breezier, not shorter and more chilling, and your nighttime scares naturally are more about running out of skim milk or finding an unfortunate puddle from your puppy on your living room floor than ghouls, blade-wielding psychopaths, or crypto-demons from the seventh plane of hell; and yet, for film studios, the horror film is never terribly far away.

There is a reason for this, of course, and it involves simple economics: Horror movies, even incredibly shoddy, barely coherent ones, tend to reap solid returns. Of the top-100 grossing films of 2014, according to boxofficemojo.com, the highest-ranking horror film, Annabelle, checks in at a modest No. 41, but of the remaining 59 films, seven are in the horror/dark thriller category, including Paranormal Activity: The Marked Ones, the fifth sequel of the found-footage franchise that may be the poster child of such low-budget/high-return studio dreams.

The original film in that series, Paranormal Activity, released in 2007, has grossed more than $193 million worldwide, which is cracking good for most releases (last year's highest grossing film, American Sniper, clocks in at about $344 million domestic, as a baseline), but absolutely, unfathomably stupendous for a film whose budget was all of $15,000! Or what you could reasonably expect to pay for Bradley Cooper's hairdresser for a few days on Sniper. And that doesn't even factor in the rest of the Paranormal franchise installments, whose collective earnings amount to about $526 million, on a collective budget on all three older sequels (the latest one is still being tabulated) of about $13 million.

With numbers like these, you begin to see why the studios are so quick to green-light a scary film, especially as the genre itself is fairly bulletproof. You don't need huge budgets, expensive star talent, or even much in the way of studio support to put out a successful scary flick, just a filmmaker with some kind of vision and a working camera or two. There, too, the filmmakers behind some very successful such films (Activity and The Blair Witch Project are but two) have used their budgetary limitations to enhance the unsettling quality of their work. Part of the reason Blair Witch worked as well as it did was precisely because none of the actors were recognizable and the shaky, hand-held quality of the camera work helped sell the idea that the film was a documentary, a true point of confusion in the early screenings of the film that led to its explosively effective word-of-mouth popularity (and this all before the age of twitter: Had Blair Witch been released last year it would have broken the Internet).

The problem, of course: Just because a film can make money doesn't mean it's any good. Many more horror films happily dispense with that whole director/vision concept and instead churn out thoroughly derivative chum to toss in the water, leaving moviegoers with a mass of floating fish heads in place of anything truly inspired. The aforementioned Annabelle was seen as a dog by most of the working critical press (a 29 percent score at rottentomatoes.com and 37 on metacritic.com), even though it made some bank. And the same could be said of a great number of horror releases over the years; the fact that they can reliably bring a substantial payout seems to indicate to many studios that the quality is pretty much secondary to the genre itself.

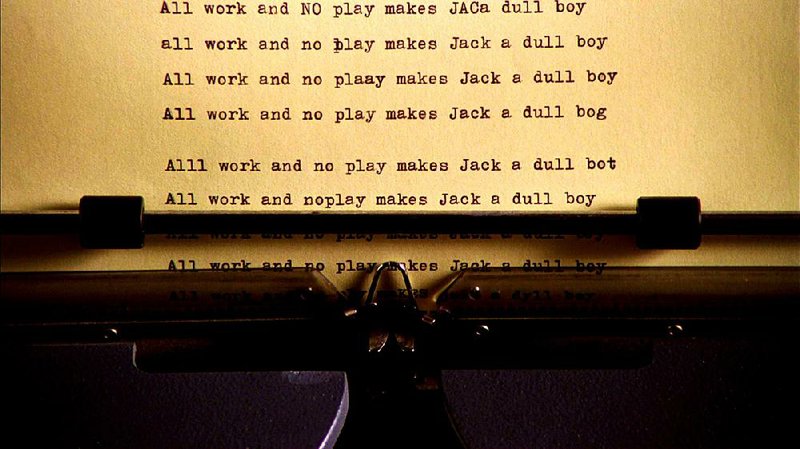

Alas, the great shame of it is no other genre speaks to our culture the way a transcendent horror film can. Few other films can shake the foundations of the zeitgeist and remain an indelible index point in a given decade, and few are honored with endless leeching and re-enacting throughout the pop-culture abyss (just think for one moment how many ways The Shining has touched pop-entertainment ever since its 1980 release, for example, or Psycho, or The Silence of the Lambs). It is a studio's stated belief that moviegoers don't actually want to be deeply scared so much as jolted out of the seat a couple of times en route to a mostly pleasurable evening of picking other people's popcorn out of their hair and screaming themselves hoarse.

The numbers might well prove that out, but it's a shame so few studios are willing to make a film that dares to be truly indelible. Throughout the decades, certain compelling qualities stand out in such films, and are more than worth noting as laws/guidelines toward making something compelling and thoroughly terrifying.

Break existing rules: For many horror fans, the act of watching a standard horror film is an exercise in rote recognition. Almost everything that happens -- the scary house, the creepy basement, the spooky psychopath, et al. -- is a call to previous films that did that exact same thing. What for one micro-generation of film fans is groundbreaking is to the next just that thing advertisers often use to sell snack chips. We might not admit it as purveyors of the genre, but for many horror lovers, there's a certain comfort taken in seeing the same old tropes tossed around. This, again, is the basis of the Scream franchise, a series of films built around the meta-concept of the horror film formula (and addressed with much more creativity and candor in the Joss Whedon-penned The Cabin in the Woods). In order to make a truly scary film, you must be willing to throw out any and all obvious reference points to earlier work and go your own path. The found-footage film started out as a way to break many of the existing rules, right until it made so much money that every other horror film released followed the same formula. Something has to be the groundbreaker for others to bite off of; it stands to reason.

Throw your audience off-balance: This comes in conjunction with our first law, and perhaps the best historic example of this was Alfred Hitchcock's 1960 classic, Psycho. Previous to that film, Hitch had been known for nearly three decades as a brilliant and wildly successful maker of thrillers, mysteries, and twisty caper films: fascinating, often surprising, but ultimately harmless. Devilishly, he traded the longtime audience trust he had built to make a film that began almost exactly like a standard film from his catalog -- an attractive young woman (Janet Leigh) impulsively steals $40,000 from her company and goes on the lam, holing up in a motel to think over her actions -- only to shatter any preconceptions with that unforgettable shower sequence, resulting in a suddenly dead heroine, and complete chaos as far as the plot line was concerned. Needless to say, audiences were thrown into such a state of terror and confusion that some of them never went back to Hitch and never forgot that shower (to this day, my mother refuses to use a shower in a hotel, even if the rest of the family is in the next room). If you can pull the chair out from under the audience, you absolutely own them for the remainder of film.

Keep it real: As fanciful as horror can be (we are dealing with a genre of supernatural beings, demonic evil, and space creatures from the planet Xeon 73, after all), the best stuff is still grounded in the real and tangible. Part of what made Alien so outstanding, and so utterly terrifying, was the naturalist ensemble acting of the principals and the grungy, thoroughly lived-in appearance of the Nostromo. It keyed as real in our brains, which set us up for the egg chamber sequence and everything that came after it. Even though the story was pure science fiction, the characters felt like real people, reacting to this unbelievable horror in hugely realistic detail. It also helped that the actual alien was a real dude in a (brilliantly designed) rubber and latex suit, which I'd take over the slick, CGI-rendered creatures that populate the far less effective sequels any time or place.

Don't ask, don't tell: It always drives me nuts when a horror film is too quick to establish its rules of engagement: It works OK with vampire movies, I suppose (sunlight = bad, garlic = safety, et al.), but in general, the more you clarify and make concrete, the less our brains have to engage. Nothing is more terrifying than the unknown, so as soon as you make it corporeal and boringly finite, you've given away two-thirds of what could have made your film scary. Another part of what made Alien so effective was that the creature kept evolving, and you didn't know quite what it was going to look like from one scene to the next. As confusing for some people as the ending of The Shining might have been, it spoke to a concept of circular evil that was very much left to our own shattered imaginations. Don't give me hard and fast parameters; give me a bunch of elements that leave me breathlessly out-of-sorts.

Come out of nowhere: As we've discussed, horror movies work best when we know as little about them beforehand as possible. Psycho was so effective in large part because Hitchcock kept everything so close to the vest. Reportedly, he bought as many copies of the original Robert Bloch novel as he could so others couldn't read it first, and he insisted on a "no late admittance" policy in all the theaters that screened it. No one was allowed in after the film started to play, which created even more buzz about what it might contain. The aforementioned Blair Witch worked as well as it did precisely because so little was known about it, also true of the early screenings of last year's critics' darling, The Babadook. We are most shocked and scared by things we don't anticipate.

Don't let up: And here's one where even the great Psycho faltered, at least a bit. At the end of the film, with Norman Bates (Anthony Perkins) safely locked up, a doctor explains in unfaltering, ridiculously assured soothing tones exactly what happened with the young man and why, giving the still-terrified audience a chance to catch their breath and climb back down into their seats a bit, reducing the chaotic tension of the film to one lone lunatic. Less than 20 years later, by contrast, John Carpenter shot the ending of the seminal Halloween to have the exact opposite effect: Evil is everywhere, can come at any time, and is virtually unstoppable. Stuff that into your goody bag.

MovieStyle on 04/10/2015