Among environmental disasters, such as increasing carbon-dioxide levels, biological extinctions equaling those caused by the asteroid collision 65 million years ago, and the half-million Americans who die annually from smoking, there is heartening news about a calamity that didn't happen.

If we'd listened, during the 1970s and 1980s, to those "Merchants of Doubt" (the title of a wonderful book by science historian Naomi Oreskes) who counseled us to ignore environmental scientists and proceed instead with production of industrial chemicals known as "chlorofluorocarbons," the world would today be paying a very high price. Stratospheric ozone concentrations would be one-fifth of their normal value, causing an extra 2 million skin cancer cases every year, among other harmful effects. By 2050, ozone depletion would be catastrophic.

Instead, scientists announced recently that stratospheric ozone concentrations are finally increasing from their present dangerously low levels. Such ozone assessments are made every four years by 300 scientists under the United Nations Environmental Program, a group that parallels the UN's Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change of about 1,000 scientists plus 2,500 scientist-reviewers.

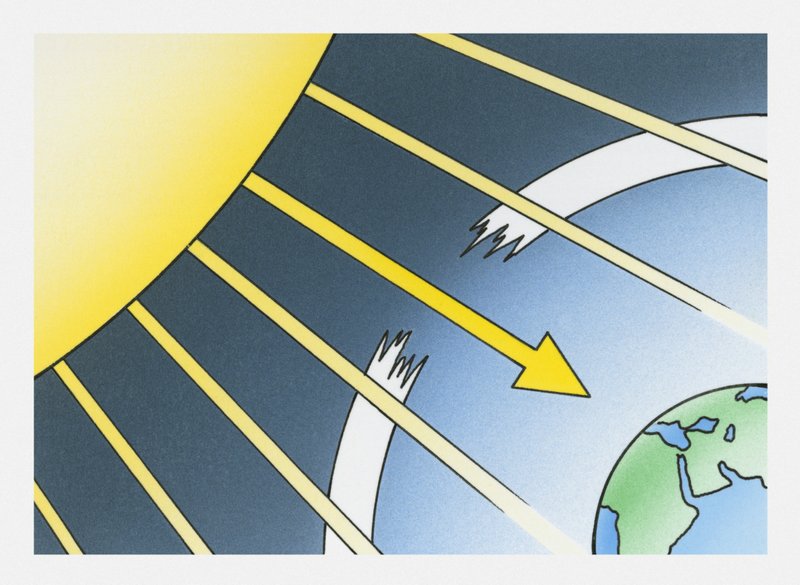

Stratospheric ozone absorbs the high-energy sunlight that would otherwise reach the ground and destroy DNA, causing skin cancer, eye damage, immune system damage and crop damage. Ozone is destroyed by the chlorofluorocarbons that were once the basis of a multibillion dollar industry that produced refrigerants, spray can propellants, Styrofoam and other items. In 1974, university chemists Sherwood Rowland and Mario Molina suggested the alarming possibility that chlorofluorocarbons drift into the stratosphere where high-energy solar radiation breaks them down, releasing chlorine and other highly reactive chemicals that then destroy ozone. As one testament to the quality of the science that uncovered the environmental virulence of these supposedly harmless chemicals, Rowland and Molina, along with environmental scientist Paul Crutzon, shared the 1995 Nobel Prize in chemistry.

As Oreskes' book rationally and eloquently documents, the same conservative interests that have always denied the link between cigarettes and cancer, between coal plants and acid rain, between secondhand smoke and cancer, between pesticides and ecosystem disruption and between fossil fuels and global warming, then pulled out all the stops to deny the science linking chlorofluorocarbons to stratospheric ozone destruction. Industrial mouthpieces such as the Chemical Manufacturers Association, conservative ideologues such as President Reagan's Secretary of the Interior Donald Hodel, conservative think-tanks such as the Cato Institute, American Enterprise Institute, Competitive Enterprise Institute, Marshall Institute, and Heritage Foundation lobbied heavily, supporting free-market policies against environmental protections.

Along with other Fayetteville environmentalists, I worked during the 1970s and 1980s for government regulation of chlorofluorocarbons. Even after 1985, when scientists discovered the catastrophic, annually recurring loss of ozone above Antarctica known as the "ozone hole," industry continued to deny the reality of ozone depletion, deny humans could cause global environmental change and deny industrial chemicals were the culprit.

Finally, the DuPont Chemical Corp. had the sense to recognize the science of ozone depletion and the catastrophe itself were undeniable. In 1988, DuPont announced it was ceasing production of chlorofluorocarbons.

This turned the bad news story into a good news story. The world cooperated to forge the Montreal Protocol, a unique and drastic international environmental treaty. It called for a complete phase-out of all ozone-destroying chemicals by the year 2000, a phase-out that has been achieved nearly everywhere and continues in force. The result is stratospheric ozone levels are finally rising, and the "ozone layer" is on track to recovery by 2050. Achim Steiner, director of the U.N. Environmental Program, calls this "one of the great success stories of international collective action in addressing global environmental change."

This is good news in an often dark landscape and sends a message of hope to those who are working to solve an even larger and more politically intractable problem, namely climate change. The world has shown it can unite to take the drastic action needed to eventually reverse this problem if the fossil fuel industry today can learn the lesson the chemical industry learned in the 1980s. But unlike the chemical industry, the fossil fuel industry has never frankly acknowledged the validity of the unprecedented scientific effort that has gone into studying climate change and certainly has not begun to act accordingly. Instead, this rich industry and their rich backers continue their denial while the world continues to suffer. The human race will not be able to turn climate change around until the fossil fuel industry learns the lesson that the chemical industry learned during the ozone dispute.

ART HOBSON IS A PROFESSOR EMERITUS OF PHYSICS AT THE UNIVERSITY OF ARKANSAS.

Commentary on 10/12/2014