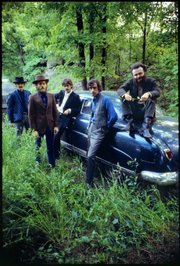

Correction: Two members of The Band were misidentified in a photo caption on Page 6E of Sunday’s Style section. The correct order is, from left, Rick Danko, Levon Helm, Robbie Robertson, Richard Manuel and Garth Hudson.

Probably the most accurate way to perceive last week's release of The Basement Tapes Complete: The Bootleg Series Vol. 11 (Columbia/Legacy), the 138-track archive of the 1967 sojourn into American roots music by Bob Dylan and the Hawks, the group of musicians who would become The Band, is as a cynical commercial venture designed to wring a little more discretionary income from baby boomers. This is yet another trophy set to display on the shelves next to The Beatles and Neil Young, an expensive ($120) six-CD set that comes with a photo book and extensive liner notes, designed to advertise one's connoisseurship.

On the other hand, it's also a deeply interesting document that's rendered more compelling by the fact that we were never meant to hear it. It's like audio cinema verite, a breaking-in on an occluded period. Nearly 50 years after the fact, we can be a bug on the wall in the basement of Big Pink, the house in Saugerties, N.Y. -- about a two-hour drive from Manhattan and 10 minutes from Dylan's house in Woodstock -- that Rick Danko, Richard Manuel and Garth Hudson rented and where Bobby and the boys (including Robbie Robertson and eventually Levon Helm) were mixing up the medicine, trying on old costumes, goofing on the weird and ancient tropes of Americana while Hudson's two-track reel-to-reel rolled.

Dylan and company recorded up to 10 tracks a day in that basement (The Band's debut album, Music From Big Pink, was not recorded there but in professional studios in New York and Los Angeles), but they were obviously not meant for public consumption. Hudson's reel-to-reel was a stenographer, mostly scratching out the minutes of the meetings, alert to moments of spark and transcendence, but mostly just robotically vigilant.

If you've wanted to, you've heard most of this before: The Basement Tapes were the most famous bootleg in history. Cuts began leaking out via a publisher's acetate -- a recording made to secure copyrights -- even before Julie Driscoll ("This Wheel's on Fire"), Manfred Mann ("Quinn the Eskimo") and Peter, Paul & Mary ("Too Much of Nothing") had hits off songs Dylan had recorded at Big Pink. By the time Columbia relented and released an official The Basement Tapes double album in 1975 (which included a couple of tracks Dylan didn't play or sing on), a lot of the recordings were readily available on unauthorized vinyl. (One of the ironies of the new release is that Legacy took extraordinary measures to protect the new collection from being pirated, to the extent that The Guardian reported that no promotional copies were being sent to critics. That's not true. I have a set of promo discs.)

Still, the company is claiming that 30 of the tracks on the new set have never been released before. There are quite a few I hadn't heard before. If I didn't have my promo discs, I might be willing to pony up for the set.

,,,

There is a conventional way of looking at the recordings; and that is to declare that Dylan and The Band were intentionally retreating from the experimentation of the psychedelic era and returning to the earthier, more organic noise of American blues and string band music. It was all rickety and weird and the lo-fi recordings emphasized the plaintive rawness of the sound, lending it an authenticity that maybe it didn't quite earn.

But people looked to Dylan then like he was some kind of weatherman. If not for the Big Pink recordings, would the Beatles have abandoned their Sergeant Pepper paintbox for the rawer sound of the Get Back sessions? Would the Rolling Stones have recorded Beggar's Banquet, or the Byrds made Sweetheart of the Rodeo, an album that featured "You Ain't Going Nowhere" and "Nothing Was Delivered," two songs Dylan wrote and recorded in the basement?

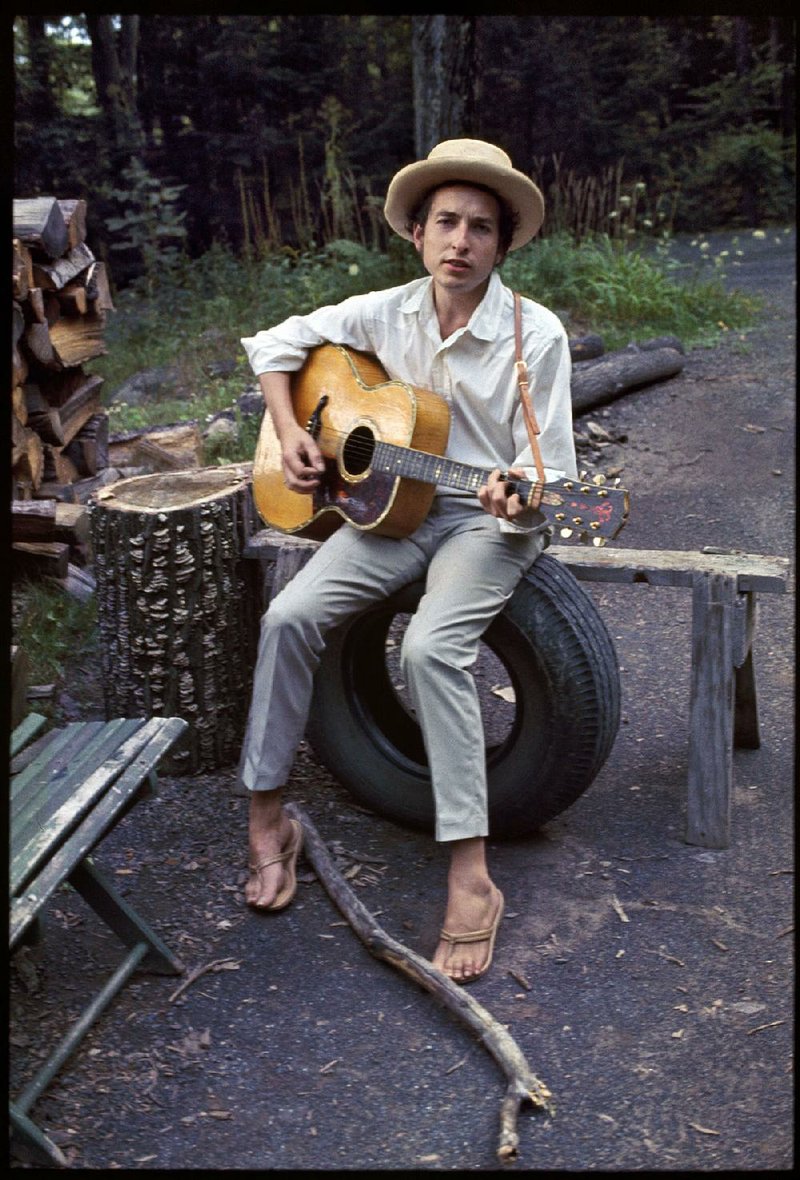

It's not difficult to locate the source of what became known as alt-country or Americana in that basement and to call it one of the primal scenes of American music history. It's where Dylan -- damaged by the reaction of folkies who resented his "going electric" and maybe by a near-fatal motorcycle accident -- repaired to record some of his most moving and mysterious recordings. From April to October 1967, while the Summer of Love raged and Vietnam elbowed its way to the fore of the American consciousness, Dylan and The Band began woodshedding.

There's a freedom in toiling in obscurity, in evading the expectations of fans and critics. Taken as a whole, The Basement Tapes evokes nothing more than a freewheeling jam session, full of obscure country-blues numbers, the spooky half-finished originals, half-serious covers of contemporaries (Ian & Sylvia's "The French Girl," the Stones' "Get Your Rocks Off"); the crazy, cheesy jumble of rollicking imaginations cut free from the expectations of ever being heard by any outsider. Dylan himself said in 1969 that the sessions were in part inspired by practical concerns; he felt pressured to write songs, not necessarily to record himself, but for other artists.

In 1984, he reiterated that he never would have released the tapes himself, although one wonders whether Columbia/Legacy would have put out the current product over his objections.

In a way, this apparently definitive release is a bit anticlimactic -- while there's stuff here we haven't heard before, there's nothing revelatory that had been held back. What has always seemed important about the Basement Tapes (not any of the official releases or the various bootlegs, but the platonic ideal) wasn't the performances (which range from staggeringly transcendent to ragged) or the material (which ranges from the silly to the solid to the verging on masterful) but the inherent mystery.

The Basement Tapes were a thoroughly American moment. While they were being recorded, Dylan was rumored wrecked or even dead. He was an artist in retreat, or maybe in exile. He was standing at a crossroads. And this is what he did for himself.

Songs such as "Yea Heavy and a Bottle of Bread," "Too Much of Nothing," "You Ain't Goin' Nowhere" and "Crash on the Levee" are hardly finished commercial products. They are more snatches of songs than recordings. They sound more half-remembered than freshly written, they dither the difference between traditional folk songs and new rock, and they are not always successful.

What they might be are private conversations between Dylan and The Band. In the basement of Big Pink, Dylan stopped becoming the Spokesman for a Generation and began to erect an insulating personal mythology. He was abdicating. He wouldn't be bigger than the Beatles, he wouldn't be the thinking hippie's Elvis Presley. Dylan might have grown up on his electric sorties of 1965-'66, with the half-electric Bringing It All Back Home, the full-tilt boogie of Highway 61 Revisited and the majestic raucousness of Blonde on Blonde, but The Basement Tapes were something he did for himself. It was a kind of regrounding in the music that Dylan, a middle-class kid from the Iron Range of Minnesota who'd thrown in with a group of Canadian hillbillies (plus Helm), needed to do for himself.

You can read The Basement Tapes as pure therapy.

But they also contain some great music. Dylan's singing is especially good here. One minute he's thunder, an Old Testament prophet racked with rage; the next he's all sassafras and moonshine, gliding along on that cool beatnik rasp; then he's doing a credible Blind Willie McTell impersonation.

The Band follows his cues when they're not mocking his mood. Hudson plays his organ like he's driving a bulldozer, finishing things off. Helm's mandolin skitters across the surface like a water beetle; Robertson's guitar crushes and molds; and the harmonies sound authentically homespun and sweet as angel breath.

We can only guess at the source of Dylan's rage and humor, at his magpie gatherings of images and tropes. We know he knows all about Harry Smith and the strange anthology the musicologist assembled; it is fair to suspect he knows far more than he's willing to let on.

At the heart of rock 'n' roll is the myth of disappearance and resurrection. Dylan went underground in the late 1960s and really hasn't emerged since. Though some would mount a rescue mission, the truth is he ain't lost -- the truth is, he deserted. The Voice of the Generation went AWOL. The Basement Tapes was a sighting, a stirring on the edge of the dark woods. No wonder we study it with the same hopeful fever some hold for alleged photographs of Bigfoot or Nessie or the aliens who walk among us.

Now we have the whole hi-res printout to examine. The amazing thing is that the mystery remains.

,,,

A week after the release of The Basement Tapes Complete: The Bootleg Series Vol. 11, on Nov. 11, we have The New Basement Tapes: Lost on the River, a project overseen by T Bone Burnett, who recruited musicians Elvis Costello, Rhiannon Giddens, Taylor Goldsmith, Jim James and Marcus Mumford to help him finish the songs.

"Not only do they have the talent and the same open and collaborative spirit needed for this to be good, they are all music archaeologists," Burnett explains. "They all know how to dig without breaking the thing they are digging."

Burnett explains that Dylan's publisher approached him with a box of lyrics that Dylan had written during 1967, while recording at Big Pink. The lyrics were distributed to the musicians, who wrote music, and the ensemble recorded 40 new songs while Sam Jones, best known as the director of the Wilco doc I Am Trying to Break Your Heart, filmed the process. The first 20 tracks have just been released, with a second disc to follow next year along with the documentary Lost Songs: The Basement Tapes Continued, which will debut on Showtime on Nov. 21.

Email:

www.blooddirtangels.com

Style on 11/09/2014