When the Little Rock School District lists its state-identified "priority" schools -- the 5 percent lowest-performing schools in the state -- Wilson Elementary is on the list.

But the name is struck through.

That's because the 295-pupil, red-brick school on the large corner lot at Colonel Glenn and Stannus roads has met or exceeded its state-set annual achievement goals to the point that Wilson is a state-named "exemplary" school.

As such, Wilson -- where every child is served free school meals because nearly all are from low-income families -- is living in rarefied air: There are only nine exemplary schools in the state for the 2013-14 school year.

Now, on the brink of receiving results from the state's 2014 Augmented Benchmark Exam, Wilson faculty members and other observers of the school are optimistic -- even nervously confident -- that the upward trajectory of pupil achievement and growth will continue.

"You get these smart kids, passionate teachers ... it's going to come together. It's going to happen," said Eleanor Cox, a veteran Little Rock district principal now completing her second year as the leader at Wilson.

Two of the state's nine exemplary schools were recognized for high performance. Others, such as Wilson, were recognized not for high scores but for sizable year-to-year achievement gains.

Wilson was specifically recognized for the gains made by pupils who are poor, require special-education services or are non-native English language learners. Students in those subgroups in Arkansas schools and in schools nationwide are at greater risk for school failure.

In the 2012-13 school year, the most recent year for which there is data, 70.4 percent of Wilson's pupils in that targeted, combined super-subgroup of children achieved at a proficient or better level on the Arkansas Benchmark literacy test. That knocked the top off the school's state-set goal of 59.85 percent for the year. About 84 percent of the Wilson test-takers made growth in literacy, topping the growth goal of 73.3 percent, according to state records.

In math, 67.35 percent of Wilson pupils in the targeted subgroup -- which is just about everyone in the school -- scored at proficient or better on the Benchmark exam, topping the school goal of 62.88 percent. A total of 68.3 percent of the children in the targeted group made growth in math, besting the 2013 goal of 61 percent.

The results are substantially better than in 2010 when 32.2 percent of Wilson pupils scored at proficient or better in math and only 26.4 percent did the same in literacy, according to district data.

Achievement goals are ratcheted up annually. And the lower the percentage of proficient students at a school, the larger the increase the school must make each year.

Wilson is an example of an academically struggling school that's getting help from all directions.

Faculty members and other observers of the school list many reasons for the school's recent achievement gains, including the school's small size, its care for the individual child, its partnerships with churches whose members mentor pupils, its analysis of student test data to identify and teach to each child's needs, and the direct services the school receives from the Arkansas Department of Education and Pearson School Achievement Services, a school-improvement company, to ensure that Wilson is using nationally researched best education practices.

"You can tell everyone Wilson is full of spirit," fifth-grader Matavius Conway, 11, said about the school he's attended for two years. "We have a lot of fun assemblies and fundraisers," he added.

Third-grader Zacorian Hickey, 9, said he, too, loved "all of the events" at the school such as the "Arc and Spark" demonstration by Entergy, Dress Up as a Favorite Book Character Day, and an afternoon, schoolwide dance to celebrate the school's exemplary status.

Zacorian talked while feeding graham crackers to Fifi, Chichi, Onyx and Diva, a collection of multicolored rats in what Zacorian said is the school's "awesome science lab."

Also high on the list of keys to success at Wilson, said staff members and outside observers, are the work and collaboration of the Wilson faculty, including its literacy and math coaches, who were hired in 2012 as trainers and resources for teachers but have also taken on the job of providing help to children, too.

Dennis Glasgow, the Little Rock district's associate superintendent for accountability, has watched Wilson over the years. The school has had an up-and-down history of achievement, he said, but when it was "put under a microscope by the state" -- the faculty members responded.

"I think they got their act together," Glasgow said. "They have good math and literacy coaches. The coaching was good, and the teachers were receptive to improving, to doing better."

Susan Ridings, the state Education Department school-improvement specialist assigned to Wilson, said literacy coach Jannette Torrence and math coach Tianka Sheard have had "a super-big impact."

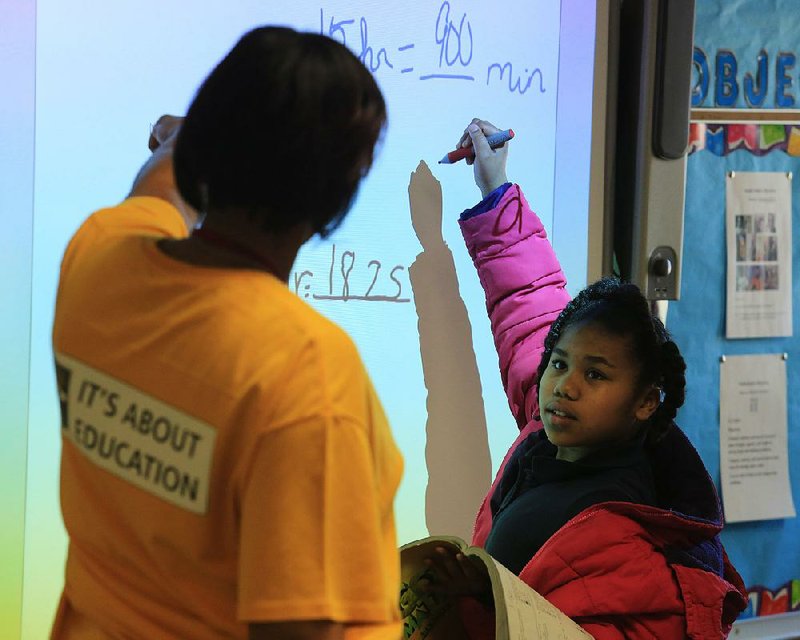

The two coaches provide job-embedded training to teachers, Ridings said. They model lessons in the classroom so teachers can see the real-life application and effect of a strategy. As a result, teachers are more willing to try something new.

The coaches also instigated a change in the school's schedule so that grade-level teachers can meet together for training and lesson planning, Ridings said. The two promoted efforts to get aides and other adults in the school -- such as the art and music teachers -- to work with children in the regular classrooms.

Torrence even has the third-graders paired with kindergartners for practice in reading and for building esteem.

"We look at the data, and then we do things that make sense," said Sheard, officially the math coach but also the data process manager for the different electronic checklists required at the school and the promoter of the schoolwide First in Math computerized math game. Weekly winners of the math game get to be in the much-desired first-in-line spot to the cafeteria and other activities.

Sheard is the also the volunteer science lab teacher and overseer of a menagerie that includes Miss Holly, the white finch; Mr. Freddy, the bearded dragon lizard; and the aforementioned rats.

"Everybody knows that if you have more than one adult in the classroom, that increases achievement," Sheard said about matching pupils to all available adults. "We need this human body touching lives. Common-sense strategies like that have helped us at Wilson. Nobody said, 'Do this,' but we said, 'This makes sense, so let's try it for the kids.'"

Sheard said she had a tough upbringing in California. She was a young teen mom to twins and didn't graduate from high school but earned an equivalency certificate at 22 when someone noticed her potential.

"I have a vested interest in this population," she said about Wilson pupils. "I came from a similar situation."

Asked how the school has made such strong academic gains, Torrence and Sheard compliment Cox for her commitment to serving all children equally and giving the faculty members the freedom to do their jobs.

"Dr. Cox is very astute at choosing particular people for certain jobs," Torrence said. "If she trusts you and knows you are going to do your job, she is going to let you do it."

Torrence worked in California for 27 years before working in Little Rock, an experience that gives her insight into working with the 20 percent of Wilson Elementary children whose families who are not native-English speakers. Those children are not lumped together in a large group but are separated into smaller groups based on specific needs, be it vocabulary help, grammar work or sentence-structure practice.

Stephanie Russell served in the military for eight years before becoming a teacher. She is in her second year of teaching and first year as a fifth-grade teacher at Wilson. She marvels at the support she has from Cox and the rest of the school.

In math, for example, the lessons are pre-made -- even the homework assignments -- and all are broken down for the different levels of student skills in the class.

"The resources are all there when I need them, so my focus is on teaching and not on making the materials to teach," she said.

Ridings, the state school-improvement specialist, praised Wilson faculty members for making good use of different kinds of student test data. The children take periodic tests or assessments that aren't really for grades but are used to pinpoint what they have learned and what needs to be retaught, possibly using a different strategy to do it.

"Mining that data and providing interventions is a huge piece of why the school is successful," Ridings said.

Ridings spends one day a week at Wilson, helping the school meet the many requirements imposed on the formerly low-performing state-identified priority school.

Even though Wilson met its annual achievement goals in 2012 and in 2013, the school must continue to comply with the extra requirements placed on priority schools for at least one more school year, Ridings said. Those requirements are part of the state Education Department's plan for meeting the federal government's school-improvement demands.

As a result of its initial identification as a priority school, Wilson underwent a scholastic audit by the state. It has since developed a very detailed Priority Improvement Plan to address the audit findings. That plan is incorporated into the regular school-improvement plan that is required for all public schools.

Pearson consultants routinely visit the school to provide training to teachers, work with Cox on a leadership skill and prepare children for state tests. The consultants also prepare weekly reports about their work for the state. Ridings also enters reports and data into a state Education Department system for tracking the priority schools.

Cox and Ridings do regular "classroom walk-throughs," with Cox swiping and tapping away at her iPad screen, recording what she observes in regard to student engagement or classroom management. That information and data from other sources are kicked out into a report form and discussed at staff meetings and acted on during training sessions.

Eight Little Rock schools were among the 48 schools statewide initially identified as priority schools in 2012 on the basis of a three-year average -- 2009, 2010 and 2011 -- showing that they were the lowest in their state test results.

Besides Wilson, the priority schools in the Little Rock School District are J.A. Fair, Hall and McClellan high schools; Cloverdale and Henderson middle schools; and Baseline and Geyer Springs elementaries. Geyer Springs is being remade into a gifted-education school for next year.

The others, which have to meet the same requirements as Wilson in regard to taking certain steps to meet achievement goals, have either recently received a new principal or will be getting a new principal this coming school year.

The pieces for improving Wilson came together faster.

"They drill it down to the individual kid," Ridings said. "That's what successful schools do and that's why they see huge growth."

Metro on 05/27/2014