Sunken lands.

The name endures like the river -- the Mississippi River that spilled over a big part of northeast Arkansas more than 200 years ago. The river made a swamp of once-dry land, but even greater forces made the land sink in three Arkansas counties.

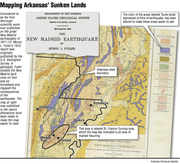

The New Madrid Earthquakes of 1811 and 1812 dealt this part of the state a peculiar blow. Stretches of land sank 20, 30, 50 feet.

"It went from abundance and woods to a swamp with mosquitoes and snakes," says Linda Hinton, director of the Southern Tenant Farmers Museum in Tyronza, population 918, in Poinsett County. The land fell in Poinsett, Craighead and Mississippi counties.

"When they started farming these lands, it was just tree stumps [from logging] and swamp," she says, "and they had to clean it out and drain it."

"Sunken lands" is partly a geologic description: ground lower than it was before the earth shook. People called it the way they saw it -- saw the tops of tall trees barely above the water -- and the name stuck.

But "sunk" is a feeling, too. Feeling low, beaten down, alone, the sense that comes through the lyrics of Rosanne Cash's song "Sunken Lands":

The children cry,

The work never ends ...

Who will hold her hand

In the sunken lands?

The sad sound of the name, sunken lands, has some truth to it as well, Hinton says -- or did. People worked hard for not much in the sunken lands.

They fought swamp water, fought bugs and fought lawsuits over land rights. The old surveys said one thing, but the river went another way. Homesteaders found new lakes on top of their land grants. Not that farming was ever easy, anyway.

But now? "It's a good place to live," she says. "People like to live here for the small towns and the schools," and the schools have ballgames.

Jobs, movie theaters and other diversions are just a half hour's drive either direction, up to Jonesboro or down to Memphis.

The new hope is tourism, as people come to see where Johnny Cash grew up and started singing -- where artist Carroll Cloar painted some of his Southern landscapes -- where some of the most incredible things on earth happened just beneath a person's feet.

"We don't feel like it's gloomy around here any more," Hinton says.

"We're rich in history."

...

"The area thus wiped off the earth came to be called the Sunk Lands."-- Greene County newspaper story "Prairie Transformed into a Series of Lakes in a Single Night," 1899.

Sunk country, some people call it.

Sunk lands.

Sunken lands. The names all mean the same: a trough between the Mississippi and St. Francis rivers.

Most old-time travelers gave up or died trying to slog west through the swamp. Those who made it to the high ground of Crowley’s Ridge had survived the worst of something special. Earthquakes have caused the ground to sink in other places, but not the same as in Arkansas.

Here, the land was practically made to collapse. It’s still the same — a loose mix of sand, silt and clay particles that geologist Scott Ausbrooks likens to a box of breakfast cereal. “Shake it,” he says, “and it packs down.”

Ausbrooks, geohazard supervisor for the Arkansas Geological Survey, finds the Cheerios analogy useful, since the real thing is hard to see. The sunken lands look as ordinary as a flat field.

On top, that mix of soil particles “is what holds together,” Ausbrooks says, “that allows you to walk across it.”

Down 20 feet is the water level: the reason why the sunken land has ditches that look like rivers. Down 3,000 feet is bedrock. Down about 6 miles is where earthquakes rumble in their sleep, even now stirring a little every few days, Ausbrooks says.

The New Madrid earthquakes worked terrible miracles: sand geysers, and the Mississippi River ran backward. Science of the time lacked the know-how to measure earthquakes, but estimates vary from 7.0 to 8.0 and more on the Richter scale, as strong or stronger than the quake that leveled San Francisco in 1906.

Today, such an upheaval would shatter homes and businesses all the way down the Mississippi River to Memphis. It would be “the worst natural disaster in American history,” highways and bridges destroyed, the end of downtown Memphis, according to author Michael B. Dougan’s Arkansas Odyssey: The Saga of Arkansas from Prehistoric Times to the Present (Rose Publishing, 1994). But frontier Arkansas was scarcely settled. In 1811, the population of New Madrid, Mo., about 400, made it the big place on the river, the one most affected. (Memphis was founded eight years later.)

People described 30-foot waves, whole shorelines of trees swallowed into the river with a cannonade sound of breaking timber, flashes of lightning that threatened to split the earth.

Named for New Madrid, the earthquakes actually centered under today’s Blytheville, and the ground had a weird trick for Arkansas: the sunken lands.

The sunken lands happened when the bedrock rattled, Ausbrooks says. The soil particles came apart, and the land dropped.

Sand mixed with water is quicksand, and “anything on top is going to sink.” He finds the thought “kind of mind-boggling and borderline scary.”

Crossing the Mississippi to Memphis on Interstate 40,” Ausbrooks says, “I definitely think about it.”

The sunken lands.

Though its name sounds faraway and fantastic, the “sunken lands” are as close as a drive north on U.S. 63 to Marked Tree and Tyronza in northeast Arkansas, up toward Lepanto, east to Dyess. Next, trek a loop to include Wilson and Whitton, too, in order to say you covered the Sunken Lands Cultural Roadway, as promoted by the Sunken Lands Regional Chamber of Commerce.

In no way foreboding, the area welcomes visitors.

The Arkansas Game and Fish Commission touts its 26,000-acre St. Francis Sunken Lands wildlife management area for “trophy-class deer” and bird-watching. Lepanto is home to the Lepanto Terrapin Derby, a turtle race. Landmarks include the late singer Johnny Cash’s boyhood home in Dyess. The bigger story lies mostly out of sight, deep in the sand, plowed and graded smooth by farm machinery. Even the savviest geologists and historians have to dig for it.

“A series of earthquakes struck the corner of Missouri and Arkansas, some of which were strong enough to ring the church bells in Boston.” — Paul Schneider, Old Man River: The Mississippi River in North American History (Henry Holt, 2013)

“People in the present day are re-evaluating the sunk lands,” historian Conevery Bolton Valencius says from the University of Massachusetts at Boston.

New understanding shapes today’s thinking on earthquakes and what happened to make the ground sink — and could again.

Little Rock native Valencius writes about the sunken lands in The Lost History of the New Madrid Earthquakes (University of Chicago Press, 2013). The book has a chapter on “Sunk Lands and Submerged Knowledge.”

The subject is so old, yet so new that the book’s research took her from “old dusty pieces of paper,” she says, to “really current scientific research.”

The New Madrid earthquakes sank from the attention of science and history, she writes, into the realm of tall tales and make-believe. Stories about the earthquakes came to sound as exaggerated as the kind of yarn that Davy Crockett would make up — and did.

Anyone might have doubted Crockett’s account of climbing into an “earthquake crack” to kill a b’ar with his knife. He also claimed to be half alligator. But there was no arguing that Arkansas wound up with a lot of mud.

“American settlers called it the Great Swamp,” the historian says. Arkansas’s prairie-turned-swamp blocked travel. Mail and messages had to be carried around the swamp. Runaway slaves hid in the swamp. Union soldiers died trying to cross the swamp. She found reference to the Great Swamp even in the words to Arkansas folk musician Jimmy Driftwood’s song “Tennessee Stud:”

Back about eighteen and twenty-five, I left Tennessee very much alive; I never would have made it Through the Arkansas mud If I hadn’t been ridin’ On the Tennessee Stud.

“Jimmy Driftwood knew his history,” Valencius says. “Arkansas mud” is the swamp, she says. And a wonder of a horse the Tennessee Stud must have been to carry a man through such a treacherous mire. “How high’s the water, Papa?” — Johnny Cash, “Five Feet High and Rising.”

Cash’s song remembers when the river flooded his dad’s 20 acres, and the family had to leave home. The swamp was all that and more.

Accounts of the time described the swamp as draped with vines, thick with mosquitoes, and the water full of snakes and 11-foot gar.

Valencius likens draining the swamp to digging the Panama Canal. The treasure beneath the receding water was the fertile soil of the flood plain. One heroic part of the job remains in place: the Marked Tree Siphons, three welded steel tubes. Nine feet in diameter, 228 feet long, these pipes were the world’s biggest of their kind the year they were installed, 1939.

The railroad came in. Towns prospered in the sunken lands. Tyronza, for one.

“It was once a busy, bustling place,” Cindy Grisham writes in When Hope Grows Weary: Tyronza, Arkansas, and Its Place in History (Cindy Grisham, 2013). Even now, she writes, “it can move the soul.”

Valencius wrote a previous book on exactly the subject of how land makes people feel, The Health of the Country: How American Settlers Understood Themselves and Their Land (Basic Books, 2004). “There aren’t many paychecks any more,” she says, out there in the fields taken over by farm machinery. But still, it’s a place “where the soil smells rich, and the cotton grows well, and the sun sets really big and red and orange.”

In the sunken lands.

(Sources include the online Encyclopedia of Arkansas History and Culture.)

Style on 05/18/2014