“The Crossroads of Memory: Carroll Cloar and the American South” is a satisfying summary of this Arkansas artist’s career. Browsing through this meticulously organized retrospective of the Earle native’s paintings is a pleasure, and the walls are filled with curious and colorful images that reinforce the idea that Carroll Cloar (1913-1993) was one of the great regionalist painters of the 20th century.

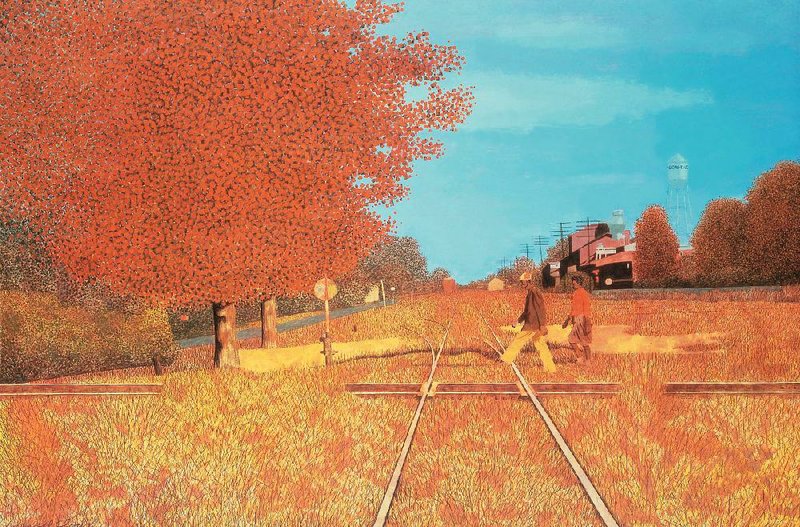

In the retrospective are familiar favorites, such as Where the Southern Cross the Yellow Dog (1965) and My Father Was Big as a Tree (1955), which usually reside in the Memphis Brooks Museum of Art. Arrival of the Germans in Crittenden County (1955) is a picture that spent time at Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art in Bentonville before appearing in this show, and the unusual and strangely beautiful Moonstricken Girls (1968) is a part of the Arkansas Art Center’s own collection.

In addition, a number of works have been gathered for this retrospective from major museums outside of our region. Among these are Autumn Conversion (1953), lent by the Museum of Modern Art in New York; Alien Child (1955), one of several gems from the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden in Washington; and The Lightning That Struck Rufo Barcliff (1955), owned by the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York.

EARLY WORK

Cloar’s early paintings from the 1950s are powerful and haunting and they steal the show. There is an incredible intensity to these images that is not fully recaptured in his later work. Cloar poured his soul into them in an effort to re-create his childhood fears and fantasies.

One of these early masterworks is the beautiful Autumn Conversion, which features three singers witnessing the religious conversion of a sinner, who sits before them, overwhelmed with emotion. At this early point, Cloar shows an impressive mastery of tempera paint, and few artists have captured the colors of autumn this convincingly.

In the haunting Alien Child, we see angst in the eyes of a young Cloar as he stands across a ravine from his relatives. A group of older kids slouch on the other side of the gully, looking sullen and disapproving. His father, mother and baby sister are far away in background. Weird, clipped trees dot an ominously craggy landscape.

There are various groups and pairs in the show. Right at the beginning we see two sports-related works. There is a precisely rendered painting of Earle football players titled The Wonderful Team (1963), and a later painting of the artist with two high school track teammates, called The Blue Racers (1971).

The eerie Gibson Bayou Anthology (1956) and several other paintings have been coupled with the amazing, full-size preliminary drawings Cloar made before painting them. It is a treat to study the artist’s working drawings compared with the finished work. In some cases Cloar’s pencil work is as exquisite as his finished art.

The Artist in His Studio (1963) features Cloar, with his back to the viewer, facing the newspaper-covered walls of his studio. Across the room from this picture is the artist’s actual drawing board and two of the newspaper-covered walls from his studio, reassembled for the show. Alongside the display is Cloar’s painting Dicey and Icyphine, Dressed Up (1979), in which two little black girls sit in front of newspaper-covered walls.

There is a section featuring Cloar’s paintings of Charlie Mae, a young black girl who was a childhood friend. One of the best of these is Been a Long Lonesome Day (1964), in which Charlie Mae sits on a can in front of a large clump of foliage as the sun sets behind her on the Tyronza River.

The dazzling, brightly beautiful Bridge Over the Bayou (1974) is an outstanding example of the slice-of-life Delta scenes that Cloar excelled at as a mature painter.

Children Pursued by Hostile Butterflies (1965) is one of the painter’s best known works, in which normally tranquil butterflies suddenly swarm a group of children. This disturbing, swirling image is unlike any other work by Cloar.

There are whimsical moments in this show. In The Rose Eater (1967), a girl watches a young boy take a bite out of a rose, and the astonished expression on the girl’s face is very funny. The Girl Tree (1964) is a slice of magic realism in which a brightly colored tree is filled with girls. Cloar’s explanation for this odd image is that during his childhood this tree was “ONLY CLIMBED BY GIRLS, NO BOYS WOULD GO NEAR IT.”

LATER WORK

As Cloar got older, his paintings began to lose some of their edge. The tight control that is characteristic of his best work began to loosen and he rehashed old themes with less conviction. Even the bright color schemes of his earlier years dimmed. This exhibition includes some good examples of his late work. The charming What Charlie Mae Dreamt (1988), and That Cold December Day (1986), a wistful scene of snow on the Delta, are especially worthwhile efforts, but even these pale in comparison to the strength of vision and technical skill seen in his earlier work.

There is a room near the end of the show with a display demonstrating Cloar’s painting process. Also in this room is a sign that reads CLOAR’S PAINTINGS REMIND ME OF A TIME WHEN …, which invites visitors to inscribe their thoughts about Cloar’s work on large sticky notes and attach them to the wall. One visitor has written “His paintings remind me of the time I met my husband, Joe, sitting on the banks of the Arkansas River fishing and chewing on a chicken leg.”

This note and other scribbled thoughts reveal an intimate connection between Cloar and his viewers. This talented artist was a beloved figure to many because his work so often features the people and landscapes of anold Arkansas they remember well. These paintings are his very personal (and sometimes strange) interpretations of Delta life from a bygone era.

Cloar brings the past to life, but it is not just his past, it’s also our past. For that, and for this definitive retrospective of his work, we can be thankful.

ALSO SHOWING

There is a very handsome book cataloging the show, which is also titled The Crossroads of Memory: Carroll Cloar and the American South. Also, in conjunction with “Crossroads of Memory,” the Arts Center has a show in the entrance hall called “Ties That Bind,” which features such luminaries as painter Louis Freund and photographer Mike Disfarmer. There is interesting work here, and it is certainly worth more than just a casual glance.

“The Crossroads of Memory:

Carroll Cloar and the American South” Through June 1, Arkansas Arts Center, Ninth and Commerce streets, MacArthur Park, Little Rock Admission: Free Hours: 10 a.m.-5 p.m. Tuesday-Saturday, 11 a.m.-5 p.m. Sunday Info: (501) 372-4000, arkarts.com

Style, Pages 49 on 03/30/2014