CHICAGO - In a stunning ruling that could revolutionize college sports, a federal agency said Wednesday that football players at Northwestern University can create the nation’s first union of college athletes.

The decision by a regional director of the National Labor Relations Board answered the question at the heart of the debate of the unionization bid: The football players who receive full scholarships to the Big Ten school do qualify as employees under federal law and therefore can legally unionize, the agency found.

“Based on the entire record in this case, I find that the employer’s football players who receive scholarships fall squarely within [the] broad definition of ‘employee,’ ” Peter Sung Ohr, the NLRB regional director, said in his 24-page decision.

An employee is regarded by law as someone who, among other things, receives compensation for a service and is under the strict, direct control of managers. In the case of the Northwestern players, coaches are the managers and scholarships are a form of compensation, Ohr concluded.

The Evanston, Ill.-based university argued that college athletes, as students, don’t fit in the same category as factory workers, truck drivers and other unionized workers. The school announced after the ruling that it plans to appeal to labor authorities in Washington, D.C.

Those advocating for letting the players unionize argued the university ultimately treats football as more important than academics for its scholarship players. Ohr sided with the players on that issue, despite Northwestern’s denials.

“The record makes clear that the employer’s scholarship players are identified and recruited in the first instance because of their football prowess and not because of their academic achievement in high school,” Ohr wrote. He also noted that among the evidence presented by Northwestern “no examples were provided of scholarship players being permitted to miss entire practices and/or games to attend their studies.”

The ruling also described how the life of a football player at Northwestern is far more regimented than that of a typical student, down to requirements about what they can and can’t eat to whether they can live off campus or purchase a car. Players put 50 or 60 hours a week into football at times during the year, he added.

Alan Cubbage, Northwestern’s vice president for university relations, said in a statement that while the school respects “the NLRB process and the regional director’s opinion, we disagree with it.”

The next step in the process of unionization would be for scholarship players to hold a vote on whether to formally authorize the College Athletes Players Association, or CAPA, to represent it “for collective bargaining purposes,” according to the NLRB decision.

The specif ic goals of CAPA include guaranteeing coverage of sports-related medical expenses for current and former players, ensuring better procedures to reduce head injuries and potentially letting players pursue commercial sponsorships.

Critics have argued that giving college athletes employee status and allowing them to unionize could hurt college sports in numerous ways, including by raising the prospects of strikes by disgruntled players or lockouts by athletic departments.

For now, the push is to unionize athletes at private schools, such as Northwestern, because the federal labor agency does not have jurisdiction over public universities.

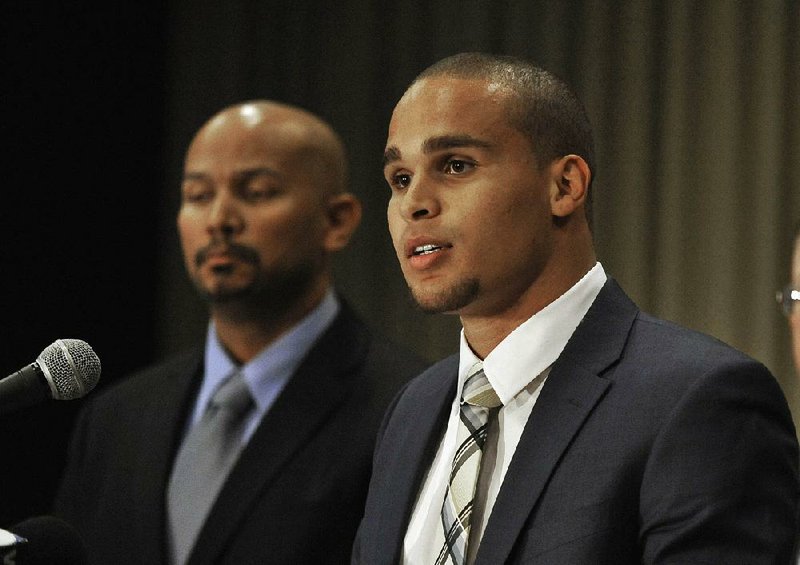

Outgoing Wildcats quarterback Kain Colter took a leading role in establishing CAPA. The United Steelworkers union has been footing the legal bills.

Colter, whose eligibility has been exhausted and who has entered the NFL draft, said nearly all of the 85 scholarship players on the Wildcats roster backed the union bid, though only he expressed his support publicly.

“It is important that players have a seat at the table when it comes to issues that affect their well-being,” Colter said in a statement issued by CAPA after the ruling.

The NCAA has been under increasing scrutiny over its amateurism rules and is fighting a class-action federal lawsuit by former players seeking a cut of the billions of dollars earned from live broadcasts, memorabilia sales and video games. Other lawsuits allege the NCAA failed to protect players from debilitating head injuries.

NCAA President Mark Emmert has pushed for a $2,000-per-player stipend to help athletes defray some of the expenses. Critics say that isn’t nearly enough, considering players help bring in millions of dollars to their schools and conferences.

In a written statement, the NCAA said it was disappointed with the NLRB decision.

“We strongly disagree with the notion that student-athletes are employees,” the NCAA said. “We frequently hear from student-athletes, across all sports, that they participate to enhance their overall college experience and for the love of their sport, not to be paid.”

Arkansas Athletic Director Jeff Long, chairman of the NCAA Football Playoff Selection Committee, declined comment through department spokesman Kevin Trainor.

SEC Commissioner Mike Slive said in a statement that conference officials are aware of the ruling but not in favor of it.

“The SEC does not believe that full-time students participating in intercollegiate athletics are employees of the universities they attend,” Slive said. “We will continue to actively pursue increased support for student-athletes by seeking to modify the NCAA governance process to permit changes that are fair to student-athletes and also consistent with what we believe are the appropriate principles of amateurism.”

Wednesday’s decision comes at a time when major-college programs are awash in cash generated by new television deals that include separate networks for the big conferences, including the SEC, which is promoting the Aug. 1 debut of its new SEC Network.

Attorneys for the CAPA argued that college football is, for all practical purposes, a commercial enterprise that relies on players’ labor to generate billions of dollars in profits. The NLRB ruling noted that from 2003 to 2013 the Northwestern program generated $235 million in revenue - profits the university says went to subsidize other sports.

Northwestern Coach Pat Fitzgerald took the stand for union opponents during the hearings, which took place for five days in February, and his testimony sometimes was at odds with Colter’s.

Colter testified that players’ performances on the field was more important to Northwestern than their in-class performance, saying“you fulfill the football requirement and, if you can, you fit in academics.” Asked why Northwestern gave him a scholarship of $75,000 a year, he responded: “To play football. To perform an athletic service.”

But Fitzgerald said he tells players academics come first, saying “we want them to be the best they can be … to be a champion in life.”

An attorney representing the university, Alex Barbour, noted Northwestern has one of the highest graduation rates for college football players in the nation, around 97 percent.

In Arkansas, there are two private colleges that dole out scholarship money to football players, NCAA Division II members Harding University and Ouachita Baptist University, although they are limited to 36 scholarships at their level.

Harding University Athletic Director Greg Harnden said he has kept an eye on the Northwestern story since CAPA was formed last month, but he was cautious when discussing the possible impact the ruling would have on NCAA Division II schools in the state.

“This is just so new that it is hard for a lot of us to even know what this means and what the long-term effects are going to be,” Harnden said.

Harnden declined to express his personal opinion regarding the Northwestern players’ argument that their scholarship checks equate them to being employees of the university, saying that it’s difficult to compare Division II programs to Division I programs.

Harding has an undergraduate enrollment of about 4,000 with athletic department revenue of about $4.1 million in 2012-2013, according to figures by the U.S. Department of Education. Northwestern took in reported athletic revenues of $66.4 million for the same year.

Harnden said the reasons Colter and other players formed CAPA don’t directly apply at the Division II level.

“We’re not benefiting off somebody from selling a jersey over at the bookstore,” Harnden said.

Information for this article was contributed by Arkansas Democrat-Gazette staff writers Troy Schulte and Bob Holt.

COLLEGE UNION RULING QUESTIONS & ANSWERS

A regional director of the National Labor Relations Board ruled Tuesday that Northwestern football players could unionize.

Does that mean some players will be able to organize and get better health care and academic support? Or does it spell the end of college sports as we know it? The Associated Press answers a few of the questions surrounding the issue:

Q◊Who came up with the idea of unionizing football players at Northwestern and why?

A◊Outgoing senior quarterback Kain Colter began the process by helping form the College Athletes Players Association, which is also affiliated with the National College Players Association, an advocacy group in California. Colter said the main thing he wanted was to make sure player medical needs were met, even after graduation. The football players are backed by the United Steelworkers, which provided lawyers and other help in seeking the NLRB ruling.

Q◊What does winning this decision mean? Will Northwestern players soon be walking a picket line?

A◊No, and there is a chance they may not end up unionized at all in the end. The decision by the regional NLRB director is an important one for the athletes to have a chance to move forward, but Northwestern said it will appeal to the full NLRB in Washington, D.C., and there is no timeline on how long a decision from the board would take to come down. “This is not a final board decision,” NLRB spokesman Gregory King said. “It’s a regional director’s decision.”

Q◊Who does this affect?

A◊Northwestern, for now, although there surely will be other efforts at other private schools should the full NLRB uphold the ruling that the players can organize as a union. The NLRB does not govern labor matters at public institutions, but it’s hard to imagine there wouldn’t be wholesale changes at those schools, too, should the union be successful in bargaining for working conditions at Northwestern.

Q◊Does this mean college players will be paid?

A◊No, although there are other developments in various lawsuits that might lead to increased stipends for college athletes.

Q◊If they aren’t getting paid, what do the players want?

A◊A seat at the table when it comes to decisions that might affect their health and future. Players want more research into concussions and other traumatic injuries, and reasonable limits on hits taken in practice. They also want insurance to cover medical costs, and guarantees they will be covered for medical issues that might arise later from their days playing football.

Q◊What does this mean for the future of the NCAA?

A◊Nothing at the moment, although anything that interferes with the organization’s model for so called amateurism in college sports may eventually force some major changes in the way big-time college sports are operated. Already there is talk in the major conferences on restructuring the NCAA and giving athletes a larger voice in their affairs.

Big Ten Commissioner Jim Delany said last month that a victory by the players would mean the NCAA would likely seek “guidance from Congress” on how college athletics should be governed. Combined with the antitrust lawsuits, there seems to be a gathering momentum for change that could alter the college sports landscape.

“This is a colossal victory for student-athletes coming on the heels of their recent victories,” said Marc Edelman, an associate professor of law at City University of New York who specializes in sports and antitrust law. “It seems not only the tide of public sentiment but also the tide of legal rulings has finally turned in the direction of college athletes and against the NCAA.”

Q◊How much money are we talking about?

A◊Tons. Big-time college programs take in more than $100 million a year from basketball and football, and the big conferences are awash in cash from both television contracts and their own networks. The NCAA has a 14-year, $10.8 billion contract for the basketball tournament, while ESPN and the major conferences signed a 12-year deal for a new college football playoff package that is reportedly worth $7.2 billion. Northwestern’s football team generated $30.1 million in revenue last year, with $21.7 million in expenses, and those numbers pale in comparison in its own conference with powerhouses like Michigan and Ohio State.

Sports, Pages 17 on 03/27/2014