“All truth passes through three stages. First, it is ridiculed. Second, it is violently opposed. Third, it is accepted as self-evident.” An epigraph from the blog Ivory-Bills Live ???! …

“See, if you see it and can’t prove it, that’s a problem.”

- Tim Gallagher

“I think anyone can come out here and see it.”

- Bobby Harrison

MONROE COUNTY - The rediscovery of the ivory-billed woodpecker marked its 10th anniversary Feb. 27, and no one cared. That is, no one but the two discoverers, Bobby Harrison and Tim Gallagher. The two paddled to the slough in Bayou DeView where they made the sighting, popped ersatz champagne (Diet Mountain Dews), snapped a photo for posterity (a blog post) and reminisced.

Anniversary marked.

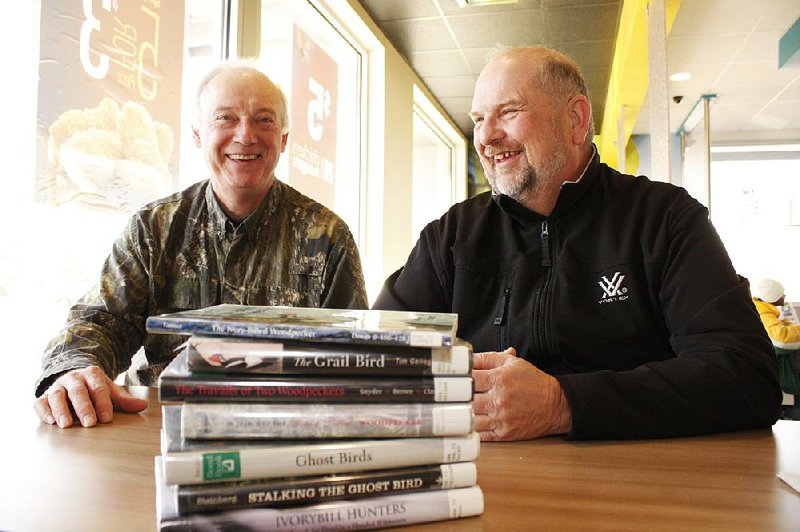

The next day, they met a newspaper reporter early in the morning at the McDonald’s off the Brinkley exit, perhaps the only one in the country that has a dedicated left turn arrow into the parking lot.

The reporter asked if they felt like a pop duo from the ’80s.

“We should be on those commercials,” Gallagher says, referring to order-by-phone music compilation advertisements. “Tim and Bobby’s Greatest Hits -”

“The one-hit wonders,” Harrison says.

“- with Engelbert Humperdinck.”

“Hey, I like Engelbert Humperdinck!”

By their count, Harrison, 59, and Gallagher, 64, have done may be a hundred presentations on their sighting and the subsequent research that culminated in a June 2005 report in Science: “Ivory-billed Woodpecker (Campephilus principalis) Persists in Continental North America.” Gallagher made a 17-hour plane trip to Cordova, Alaska, for the Shorebird Festival. Harrison has been to 24 states and three Canadian provinces to speak.

“I really enjoyed traveling and doing the programs. I love to entertain,” Harrison says.

“Especially when we’d do ’em together. It was almost like comedy. It was really funny.”

Less funny is the direction prevailing scientific opinion has turned on this bird, from cautious certainty of an extant population to skepticism to apparent disinterest.

“I don’t know what they saw,” says Katie Jacques, editor of the Argus-Sun newspaper in Brinkley, “but if there was an ivory-bill, they would have found it.”

The woodpecker, whose name is usually shortened to “ivory-bill” and has been called at least six other appellations - the ghost bird, the Grail bird, the Holy Grail of birds, el carpintero real (Spanish, “the royal carpenter”), poulet d’bois (French, “chicken of the woods”), and, most famously, the “Lord God bird,” so named because that’s what people shout when they see it - has become like Pluto. That is, a backslide, a screw-up in a pursuit - science - that marks discoveries in one direction only, forward.

“Uncertainty is just something we are going to be forced to live with,” says Gene Sparling, a Hot Springs artist and outdoorsman whose cryptic reference on a canoe club listserve to “a Pileated woodpecker that was way too big” he saw in February 2004 first drew Harrison and Gallagher to our eastern bottomlands.

“It is likely that the individual I saw in Bayou DeView is no longer alive, just because of age,” he says. “That species is not likely to live that long, and certainly … we did not find a breeding population, and that’s really what’s critical.”

Sparling, along with Harrison and Gallagher and 14 others, are named authors of the Science report.

CASHING IN

Starting in 2005 and continuing in 2006, Harrison took back-to-back sabbaticals from Oakwood University in Huntsville, Ala., where he’s a communications professor, to live in a guide-house out at Mallard Point Duck Club and spend his days in camouflage surveilling the Big Woods from a canoe. In the process, he ate at every local restaurant and made fast friends with locals.

“My wife has a list of friends she visits here. I call out to Gene’s” - Gene De-Priest of Gene’s Restaurant - “every once in a while just to see what’s going on. Ask, ‘Hey, any new businesses come in town?’ The answer’s always no.”

“The other night we were there and he was telling us all who’s died,” Gallagher says.

“He’s got a sign out front, ‘Home of the Ivory Bill Burger.’ He used to have a certificate for people who’d eaten the burger,” Harrison says.

“There used to be a place, Penny’s [Hair Care], that gave Ivory Bill haircuts, with red spray, spikey.”

Of the dozen or so books about the bird available at the Central Arkansas Library System, only one, The Ivory-billed Woodpecker by James T. Tanner, was published before 2004. There have also been at least three documentaries, two films, one popular indie folk song (Sufjan Stevens’ “The LordGod Bird” and countless television and print stories. Then, of course, there’s the woodpecker-theme state license plate, purchase of which contributes $25 to the Game and Fish Commission’s Game Protection Fund. To say that the much-publicized sighting made Feb. 27, 2004, briefly spawned a cottage industry isn’t an overstatement.

“Gene [DePriest] has really tried to cash in. Everybody has,” Harrison says. “It’s too bad we didn’t get good video. It probably would’ve been a boon for Brinkley if we had.”

“The people who made the most money off the ivory-bill was Cornell [University]. Period. They made the money off the bird. Period. They, and the Nature Conservancy,” Jacques says.

FALLING OUT

Scratch the surface of this nature-loving search for the South’s late apex woodpecker and you find human fallout.

“So much of the people who did the behind the-scenes work, why they worked so hard so long, [it was] the conservation,” says Sparling, who guided Gallagher and Harrison into the swamp Feb. 27, 2004, and took the video of them explaining their sighting immediately after. “There were some people went on a foolish and stupid campaign to become the ‘rediscoverers’ of the ivory-bill. I was not one of those. You won’t hear me ever claim to be the ‘rediscoverer’ of the ivory-bill. I was in it just for a magnificent habitat.”

There is no doubt that the attention the state received helped the Nature Conservancy in Arkansas, says Scott Simon, its director. It also marked a surge in cooperation among groups like the state’s Natural Heritage Commission, Canoe Club, Audubon group and the Game and Fish Commission, as well as the federal Natural Resource Conservation Service and Fish and Wildlife Service.

The boat launch Harrison and Gallagher used Feb. 27 and 28 is located on Benson Creek Natural Area, owned jointly by the Arkansas Natural Heritage Commission and The Nature Conservancy. The Bayou DeView Water Trail was scouted and mapped by the Canoe Club in partnership with the Arkansas Game and Fish Commission. Over the past 10 years, private landowners in the Big Woods have enrolled over 25,000 acres of frequently flooded and low production farmland in the Wetland Reserve Program, which has been reforested by the Natural Resource Conservation Service.

“Nobody previously was going into the [bottomland] woods outside of hunting for canoeing and kayaking recreation, but it is a really unique experience.”

Another unique experience 10 years after the rediscovery: Ask anyone close to the search if the ivory-billed woodpecker exists today.

“Let me just think if I can answer that,” Simon says.

He is one of the 17 authors of the Science report.

“Or how I would answer that.”

A long moment passes.

“I think you should read the Science article, actually. That’s not meant as a dodge answer. I think it actually would be more interesting [if] … you decide, based on that, was there a bird there? Was there a bird in Arkansas?”

No one is a more earnest apostle than Harrison, not even Gallagher. “Well, I wonder if somebody won’t have to come in with a dead ivory-bill in their hand !”

MANNING UP

The Science report says eight experienced, educated observers made visual contact with a bird they’re all confident is an ivory-billed woodpecker. One, David Luneau, captured four seconds of low-quality video that nevertheless yields “five diagnostic features [that] allow us to identify the subject as an Ivory-billed Woodpecker.”

It also says the extensive field survey turned up few recorded bird calls (telltale “kents” and double-knocks), but no evidence of a population or breeding (specifically, a nest).

There is a near-history of field researchers and birders - some Ph.D. ornithologists - whose reputations have been sullied by their insistence of new proof of ivory-bills. The most famous of these is probably George Lowery, director of Louisiana State University’s Museum of Natural Science, who showed up at the American Ornithologists’ Union meeting (where once he had been president) in the summer of 1971 with two Kodak Instamatic photos of an ivory-billed woodpecker in a tree. The photos clearly depict a male of the species - so clearly, in fact, that skeptics said it was a taxidermied specimen planted 40 feet up a tree trunk. Disbelief prevailed, and today, ornithologists generally consider moving images taken in 1935 as the last clear recorded evidence.

“There’s this history of people who had said they’d seen the bird but hadn’t come up with that irrefutable video or clear picture, and they had been roundly criticized by the academic community,” Simon says.

“So the researchers [in early 2005] are considering putting their research into a scientific article, [but] there’s people here at the beginning of their careers, and they’re thinking, ‘What’s my career in ornithology going to be?’ Because they knew they didn’t have the really clear picture. … They’re talking this through, and one man” - here Simon chokes up remembering - “one man says, ‘You know, I woke up this morning, and I looked myself in the mirror, and thought, “You know, we got all this data. People here have seen the bird’” - and this gentleman had seen the bird - ‘and he’s saying, “Can I go forward with my career and not confidently describe what we’ve observed and recorded for fear of being criticized?”’

“That was an incredible thing. Them working through that, knowing … that they would be roundly criticized. That no one may ever see [another one] or believe them.”

FORGING AHEAD

On Feb. 28, Harrison and Gallagher paddled out to the spot where it all started for them. They’re especially animated recalling the adrenaline rush afterward.

“It’s so funny, I’m a little bit ahead of Tim,” on the shore, now, Harrison says, “and the bird is gone, and I turn around, and here’s Tim, and his eyes are [wide]. I says to him, ‘That was an ivory-billed woodpecker!’ And he says, ‘Well, I don’t know about you, but that was a lifer for me!’”

A “lifer” is a bird witnessed in the wild for the first time.

“Well, Bobby’s crying. He’s fallen onto the ground,” Gallagher says.

“The shock was unbelievable.”

“He’s cried in interviews since. They’ve started calling him Sobbin’ Bob.”

“It really was a lifer. It has changed my life forever. And it has ruined so many people, but fortunately, I still have a job.”

Both of these men have slowed down, moved on, not given up. Gallagher has more recently searched for the ivory-bill’s nearest cousin, the imperial woodpecker, in the illicit-drug-growing lowlands of Mexico. Harrison is a proud new granddad who gets out to eastern Arkansas only about three times a year.

If they’re involved in another sighting, it likely won’t be in Arkansas. It likely will be following up on a lead (as they did Sparling’s), maybe in Florida, Louisiana. Remote capture of images or audio is more likely still.

“I don’t want to go into detail what we’re doing out there, but the idea is to attract a bird,” Harrison says.

Nothing in the last 10 years has them any less certain that there are surviving ivory-bills in the hardwood swamps of the South. Both stand by their sighting. Harrison says if he was given six months to spend in the Big Woods, he’d have another one.

The Cornell Lab of Ornithology (birds.cornell.edu/ivory) has updated information on the bird, including a guide for reporting a sighting, and a link to the 2010 U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Ivory-Billed Woodpecker Recovery Plan, which would go into effect should a population be “rediscovered.”

Style, Pages 47 on 03/16/2014