Colombia's Santos defeats challenger

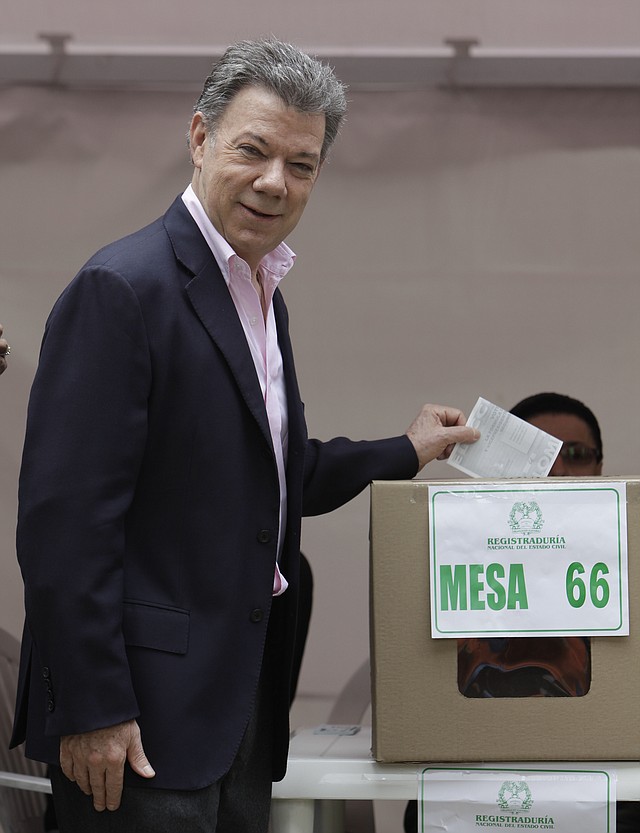

President Juan Manuel Santos casts his ballot during presidential elections in Bogota, Colombia, Sunday, June 15, 2014. Santos is seeking a second four-year term as candidate for the Social Party of National Unity.

Monday, June 16, 2014

BOGOTA, Colombia -- Juan Manuel Santos convincingly won re-election Sunday after Colombia's tightest presidential contest in years, an endorsement of his 18-month-old peace talks to end the Western Hemisphere's longest-running conflict.

Santos defeated right-wing challenger Oscar Ivan Zuluaga with 53 percent of valid votes, with 98 percent of precincts reporting less than an hour after polls closed.

Zuluaga was backed by former two-term President Alvaro Uribe, who many considered the true challenger.

They had accused Santos of selling Colombia out in the Cuba-based negotiations and insisted Zuluaga would halt the talks unless the rebel Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia ceased all hostilities.

The outcome affirmed Santos' position that he has steered Colombia to a historic crossroads after a half-century of conflict that claimed more than 200,000 lives, most of them civilians.

The campaign has been the Andean nation's dirtiest in years, and Uribe continued to allege widespread fraud by the Santos camp right up to the closing of polls.

Zuluaga shocked the incumbent's camp by outpolling Santos in the May 25 five-candidate first round of voting. Zuluaga and Uribe had accused Santos of offering impunity to the rebels.

Bogota industrial designer Felipe Quintero said he voted for Zuluaga, a previously little-known former Uribe finance minister, because Santos is conceding too much to the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia in the peace talks to end a half-century-old conflict that has claimed more than 200,000 lives.

"They need to be punished, not to be rewarded with liberty" and seats in Congress, said Quintero. "They are murderers. Why are they going to get privileges when they have killed a lot of people and keep killing?"

Santos, 62, denied he would let war criminals go unpunished. He helped professionalize Colombia's U.S.-backed military and wielded it to badly weaken the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia, including killing its top three leaders.

The bulk of Colombia's left endorsed Santos, a University of Kansas-educated economist and veteran of three Colombian presidential Cabinets prior to his own presidency. He also got the backing of 80 top business leaders last week as he announced exploratory talks with the National Liberation Army, Colombia's other, far smaller rebel band.

Beyond betting his future on peace, Santos has improved ties with the leftist governments of neighboring Venezuela and Ecuador, a sharp contrast to Uribe.

Yet the incumbent has a "severe likeability and trust problem," said analyst Adam Isacson of the Washington Office on Latin America, saying the president has been "unable to shake the image of an out-of-touch Bogota aristocrat who will promise everything and deliver little."

Bogota business consultant Maria Eugenia Silva cited a big reason many Colombians voted for Santos despite his faults: Uribe.

"The eight years he was president were a time of some of the worst corruption and biggest scandals," she said.

With Uribe the power behind Zuluaga's bid, a victory for his candidate would have lessened chances the former leader could face prosecution for purported crimes, including human-rights violations.

Blemishes of his 2002-10 government included extrajudicial killings of innocent civilians to boost military body counts, illegal spying on judges and journalists and the funneling of agricultural subsidies to well-heeled ranchers.

Zuluaga was backed by cattle ranchers and palm oil plantation owners, beneficiaries of a deal Uribe made with far-right paramilitaries that dismantled their militias. Big landholders had by then consolidated control over territory that the militias had largely rid of rebels while driving at least 3 million poor Colombians off their lands. As part of the Santos-negotiated peace process, those stolen lands would be returned.

The slow pace of peace talks did not help the incumbent. Framework agreements have been reached on agrarian measures, dismantling the illegal drug trade and creating a role for rebels in national politics.

Still, the peace process ranked relatively low on most Colombians' list of priorities. For many, spreading the benefits of a growing economy is more important.

Economic growth averaged 4.5 percent annually during Santos' four years, and 2.5 million jobs were added. But analysts said the president has done little to improve education, health care and infrastructure.

Information for this article was contributed by Cesar Garcia and Libardo Cardona of The Associated Press.

A Section on 06/16/2014