There's a biblical link to the title of the newly published memoir by Genevieve Grant Sadler, who moved from a comfortable California life to rural Arkansas for seven years in the 1920s.

The connection is an Old Testament verse from Deuteronomy, printed on an otherwise blank page at the start of Muzzled Oxen: "Thou shalt not muzzle the ox when he treadeth out the corn."

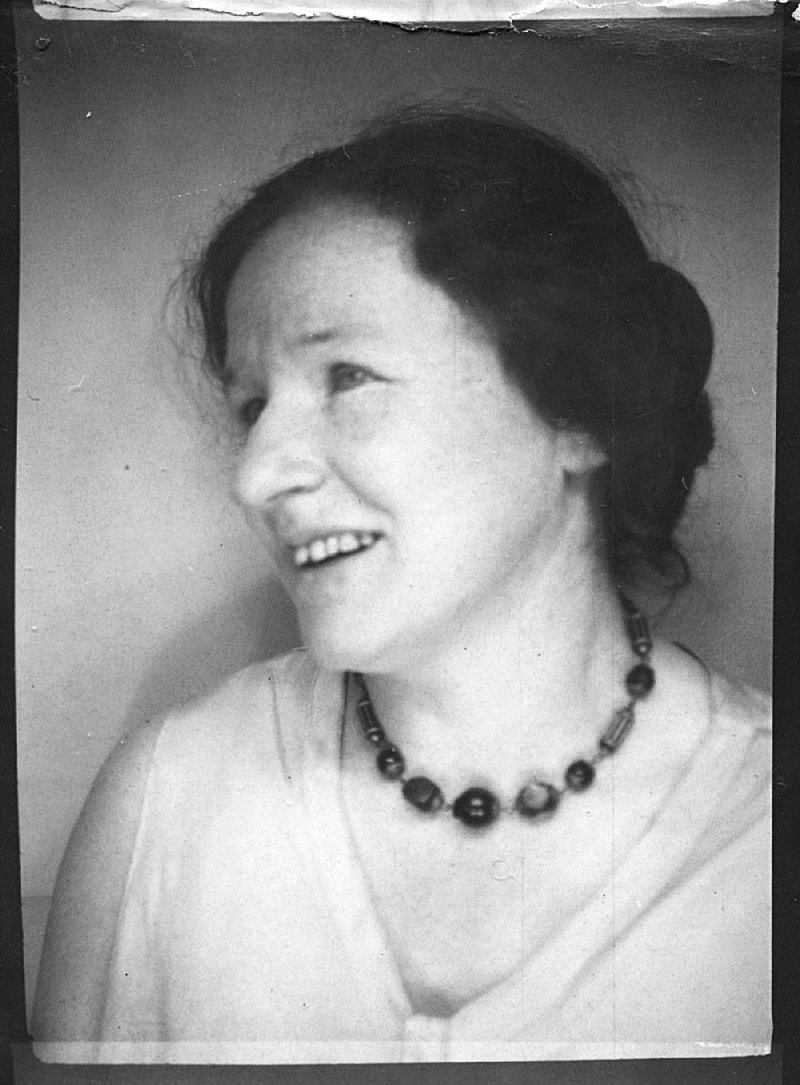

The intrepid author, known as "Brick" because of her red hair, came with Arkansas-born husband Wayne and two young sons from Santa Cruz, Calif., to his native Yell County in 1920. A third son was born on their Carden Bottoms cotton farm in 1924.

Sadler's bittersweet book, subtitled Reaping Cotton and Sowing Hope in 1920s Arkansas (Butler Center Books, $23.95), was distilled from the hundreds of letters she'd written to her mother back in California. One passage helps explain the somewhat inscrutable title:

"I went there [Arkansas] a rebellious and homesick young woman, hating even the way the grass grew in that so-foreign land. I departed, years later, with a deepened understanding of the teeming life of the land, and of the friends I left behind me -- kindly, courteous, hardworking people, uncomplaining under the most unsatisfactory conditions. Indeed, to me, muzzled oxen."

These "oxen" were sharecroppers and other hardscrabble neighbors who worked the land like beasts of burden. They were (to Genevieve's eye) too meekly accepting of their lot in life. They labored for slight reward while rarely complaining. Like the biblical ox, they deserved a fairer fate.

That point of view lends Muzzled Oxen a tone more often bitter than sweet, despite the author's claimed affection for "the teeming life of the land." At the same time, her empathetic eye for human detail propels a vivid time trip to an era when telephones were rare in rural Arkansas, snuff sticks were implements of pleasure and malaria still plagued farm families.

Son Gareth W. Sadler, who died in California in late March, described in the book's foreword the challenges that faced his parents in Arkansas:

"The hard work of planting, tending and picking cotton was overburdened by a host of problems, including the boll weevil, malaria, lawsuits and finally flood waters. In 1927 the entire Mississippi River basin ... experienced one of the greatest floods in its history. The Mississippi and all its tributaries overflowed their banks and busted their levees. The Arkansas River flooded the land for miles on either side. It put many feet of water over the Sadler farmlands and washed our family back to California."

Seven years earlier, having driven their Model-T halfway across America, the Sadlers pulled into Dardanelle. The memoir's very first sentence provides a jolt:

"A wave of hatred, a burning resentment, swept through me, leaving me speechless and limp as I sat in our old Ford car parked by the drug store and looked up and down the street. How I hated it all!"

That initial impression included "one short dirty main street, with papers lying about. The barber busily sweeping his hair trimmings from his floor across the sidewalk and into the street where Negroes straggled by. Small stores where listless men and boys lounged in the entrance. The unpaved street ... seemed to be composed of nothing but soft, deep, dry soil that sent up a cloud of dust with every passing vehicle."

On their farm, the Sadlers had two sharecropper families. They are described in terms that some readers may find endearing, others condescending:

"These Southerners were simpler, unaffected, real, going their own way, aping nobody. Each ... met his days successively, year in and year out, with a calm philosophy, even in the face of almost fated failure. Each seemed to take the same indispensable place in the social scheme of men here on the cotton farms that the common earthworm does in the plan of creation."

Bygone habits are recounted in some of the book's most vivid passages, as in this account of a sharecropper's wife's tobacco habit:

"While the men talked of crops and rentings and conditions in general, I was busy admiring the skill with which Mrs. West managed her snuff dipping. Her snuff tin, a small round can about two inches high, she carried in her apron pocket.

"'You jest get you a good stick offen some tree like the elm, that chews up good to a brush, that's all,' Mrs. West advised me. 'Didn't ya never dip none?'

"The snuff stick was well wet with saliva, then worked around in the powdered tobacco until a ball of the stuff was sticking to the end of it. This she put carefully into one cheek, the rest of the time spent, of course, in spitting, while the brown stain ran down the sides of her mouth."

Very near the end of Muzzled Oxen, as Genevieve is packing to go back to California, she asserts continued puzzlement at the Arkansans she's gotten to know:

"Sometimes I wondered what impelled them, having so little stimulation or incentive, to arise each day and live so calmly, so serenely."

She ponders how the sharecroppers "must feel to be forced into submission to an intolerable, hopeless economic life ... effectually trapped for all time. I read once of a man who trained a starling to talk. It sat in its cage and called, 'I can't get out -- I can't get out.' These people were not starlings, wanting out. They seemed not to know that they were 'in.'"

In Genevieve Grant Sadler's eyes, they were muzzled oxen.

Style on 07/13/2014