TOKYO - After a night of heavy drinking at the Globe and Anchor, a watering hole for enlisted Marines in Okinawa, Japan, a female service member awoke in her barracks room as a man was raping her, she reported. She tried repeatedly to push him off. But wavering in and out of consciousness, she couldn’t fight back.

A rape investigation, backed up by DNA evidence, ended with the accused pleading guilty to a lesser charge, wrongfully engaging in sexual activity in the barracks. He was reduced in rank and confined to his base for 30 days, but received no prison time.

Fast-forward a year. An intoxicated service member was helped into bed by a male Marine with whom he had spent the day. The Marine then performed oral sex on the victim “for approximately 20 minutes against his will,” records show. The accused insisted the sex was consensual, but he was court-martialed, sentenced to six years in prison, busted to E-1, the military’s lowest rank, and dishonorably discharged.

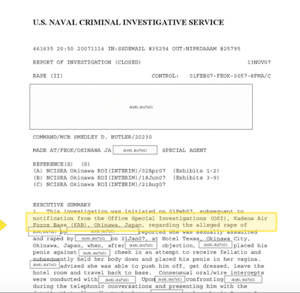

The two cases, both adjudicated by the 1st Marine Aircraft Wing, are among more than 1,000 reports of sex crimes involving U.S. military personnel based in Japan between 2005 and early 2013. Obtained through the Freedom of Information Act, the records open a rare window into the world of military justice and show a pattern of random and inconsistent judgments.

The Associated Press originally sought the records for U.S. military personnel stationed in Japan after attacks against Japanese women raised political tensions there.

Nearly two-thirds of 244 service members whose punishments were detailed in the records were not incarcerated. Instead they were fined, demoted, restricted to their bases or removed from the military. In more than 30 cases, a letter of reprimand was the only punishment.

Among the other findings:

The Marines were far more likely than other branches to send offenders to prison, with 53 prison sentences out of 270 cases. By contrast, of the Navy’s 203 cases, more than 70 offenders were court-martialed or punished in some way. Only 15 offenders were sentenced to time behind bars.

The Air Force was the most lenient. Of 124 sex crimes, the only punishment for 21 offenders was a letter of reprimand.

Victims increasingly declined to cooperate with investigators or recanted, a sign they may have been losing confidence in the system. In 2006, the Naval Criminal Investigative Service, which handles the Navy and Marine Corps, reported 13 such cases; in 2012, there were 28.

Taken together, the sex crime cases from Japan, home to the largest number of U.S. military personnel based overseas, illustrate how far military leaders have to go to reverse a swelling number of sexual assault reports.

U.S. Sen. Kirsten Gillibrand, who leads the Senate Armed Services Subcommittee on Personnel and a group of lawmakers from both political parties pressing for further changes in the military’s legal system, said the records are “disturbing evidence” that there are commanders who refuse to prosecute sexual-assault cases.

“The men and women of our military deserve better,” said Gillibrand, D-N.Y. “They deserve to have unbiased, trained military prosecutors reviewing their cases, and making decisions based solely on the merits of the evidence in a transparent way.”

Air Force Col. Alan Metzler said the Defense Department has been open in acknowledging that it has a problem.

Metzler, deputy director of the Defense Department’s Sexual Assault Prevention and Response Office, said the changes in military law and policy made by Congress and the Pentagon are creating a culture where victims trust that their allegations will be taken seriously and perpetrators will be punished. The cases in Japan preceded changes the Pentagon implemented in May, according to defense officials.

The military, Metzler noted, is making progress. Thenumber of sexual-assault cases taken to courts-martial militarywide has grown steadily, from 42 percent in 2009 to 68 percent in 2012, according to department figures. In 2012, of the 238 service members convicted, 74 percent served time.

That trend is not reflected in the Japan cases. Out of 473 sexual assault allegations against sailors and Marines between 2005 and 2013, just 116, or 24 percent, ended up in courts-martial.

Further, the 238 convictions in 2012 are a small number compared with the estimated 26,000 sex crimes that may have occurred that year across the military, according to the department’s anonymous survey of military personnel. Sex crimes are vastly under reported in both military and civilian life.

The Pentagon has said its commanders have been using nonjudicial punishment less frequently in recent years. But the documents show that in Japan at least, U.S. commanders are using that authority more often. This is especially true in the Navy, where in 2012 only one case led to court-martial. In the 13 others, commanders used nonjudicial penalties rather than ordering trials.

The authority to decide how to prosecute serious criminal allegations would be taken away from senior officers under a bill crafted by Gillibrand and expected to go before the Senate as early as this week. The legislation would place that judgment with trial counsels who have prosecutorial experience and hold the rank of colonel or above.

Senior U.S. military leaders oppose the plan, saying it would undermine the ability of commanders to ensure discipline within their ranks.

“Taking the commander out of the loop never solved any problem,” said U.S. Sen. Lindsey Graham of South Carolina, a former Air Force lawyer who is the personnel subcommittee’s top Republican. “It would dismantle the military justice system beyond sexual assaults. It would take commanders off the hook for their responsibility to fix this problem.”

The military leadership’s time to solve the crisis on its own has run out, according to Pentagon critics. A string of episodes in which senior officers were caught behaving badly is further proof that serious crimes should be dealt with outside the chain of command, they say.

“There is a perception out there right now that the military is out of control,” said K. Denise Rucker Krepp, a former Coast Guard officer and attorney. “You are not going to attract the best and the brightest if people believe that if you go into the military you are going to be sexually assaulted.”

Many of the Japan cases involved accusers who said they were sexually abused while too drunk to consent, or even unconscious. That makes it all the more difficult to determine whether a crime occurred.

“Weakness is a great fear in the military and something to be avoided,” wrote Mark Russell, a psychologist and former Navy commander who was stationed in Japan. “Therefore, women (or men) who go out drinking and are raped are often viewed as culpable for having been ‘weak and vulnerable.’”

When compared with broader statistics released annually by the Pentagon, the documents suggest that U.S. military personnel based in Japan are accused of sex crimes at roughly the same rate as their comrades around the world.

But bad behavior in Japan by American sailors, Marines, airmen and soldiers can have intense repercussions in this conservative, insular country, an important U.S. ally. This is especially true on the island of Okinawa, home to barely 1 percent of Japan’s population but about half of the roughly 50,000 U.S. forces based in the country.

Sex crimes against Okinawans have become major news stories and added fury to protests against the U.S. military’s presence on the island.

Catherine Fisher, an Australian and longtime Japan resident, accused the Japanese and U.S. governments of “harboring the suspect” after she was purportedly raped by an American sailor in 2002.

Japanese prosecutors refused to pursue criminal charges for undisclosed reasons, but in 2004 the Tokyo District Court ruled in a civil case that Fisher had been sexually assaulted, and awarded her $30,000 in damages.

By then the accused, Bloke Deans, had left the country. Fisher and her attorneys said the Navy was aware of the Japanese court case against Deans, but gave him an honorable discharge and allowed him to leave the country without informing the court or her.

Congress late last year passed numerous changes to the military’s legal system in an effort to combat the epidemic of sexual assaults.

The defense policy bill scaled back but did not eliminate the role senior commanders play in sexual-assault cases. Officers who have the power to convene courts-martial were stripped of their authority to overturn guilty verdicts reached by juries, and should they decline to prosecute a case, a review of the decision must be conducted by the service’s civilian secretary.

The argument for keeping commanders involved in sexual assault cases received a boost from a panel of experts, which said last month that there is no evidence that removing commanders from the process will reduce sex crimes or increase the reporting of them.

“I don’t know how we can trust our commanders to train our sons and daughters to fight and win our nation’s war and yet not trust them to provide and establish a command climate that provides each and every soldier a safe working environment,” said Ann Dunwoody, the Army’s first female four-star general.

Gillibrand and her supporters argue that the cultural shift needed to lower the incidence of sexual assault in the military won’t happen if commanders retain their current role in the legal system.

“Skippers have had this authority since the days of John Paul Jones and sexual assaults still occur,” said Lory Manning, a retired Navy captain and senior fellow at the Women in the Military Project. “And this is where we are.” Information for this article was contributed by Leon Drouin-Keith, Monika Mathur and Rhonda Shafner of The Associated Press.

Front Section, Pages 1 on 02/10/2014